Beyond the Headscarf: “Woman. Life. Freedom” and the 2022 Protests in Iran

By Persis Karim

November 10, 2022

Mahsa Jina Amini, a 22-year-old Kurdish woman, was arrested and brutally beaten by Iran’s morality police in Tehran on September 13. Amini’s death was reported three days later by journalist Niloofar Hamedi (now herself in prison). Amini’s death has unleashed some of the largest and most-enduring protests since the government of the Islamic Republic was established after the 1979 revolution. But these protests are not new; they are part of a long series of attempts to address, reform, and change the discriminatory legal codes and social practices that have made women second-class citizens in Iran.

Leva Zand, Roshanak Rahimi, Farnaz Zabetian, and Mojgan Saberi in front of a mural they painted at the Abrams Claghorn Gallery in Albany

In the first days of the protests, the focus was on the brutality and humiliation of Iran’s morality police and compulsory hijab laws, and the slogan “Woman. Life. Freedom.” could be heard from the women and girls leading the protests. (This slogan was adopted from the women of Kurdistan and their own struggle for autonomy against Iran’s effort to displace and disenfranchise this ethnic minority.) Since then, the protests have expanded to focus on decades of frustration with the government and daily life in Iran. They have grown to include men, boys, and people of all ages, and aim to end decades of corruption, discrimination of religious and ethnic minorities (such as the Kurds), economic poverty, environmental crises, and widespread censorship, as well as persecution of journalists. This critical moment is a response to decades of humiliation and repression at the hands of the government of Iran, which has time and time again treated protests as a threat to its very existence.

The longevity of the protests is all the more remarkable because within days of Amini’s death, the government almost completely shut down the internet, and has since arrested more than 14,000 people and killed more than 300; of those killed, at least 39 have been children under the age of 16. While Iranians have not been surprised by the government’s response, the bravery and courage of women and girls has inspired people around the world. They have burned their headscarves and danced around the streets with their hair uncovered. School-age girls have even shouted down representatives of the government.

Views of cube is NOT geometric installation by Iranian-American multidisciplinary artist and educator Pantea Karimi exhibited at the Mercury 20 Gallery in Oakland until November 26

These protests have been led by Iran’s Gen Z citizens, young men and women who have grown up under Iran’s strict legal and social codes (gender separation in schools and university cafeterias), while being integrally connected to the rest of the world through cell phones and social media. These young people, many of them high school and university students, have grown up watching their parents and grandparents grow weary of the effects of US-backed sanctions and a government that spends its oil revenues not on the needs of its growing population, but on expanding its regional power and lining the pockets of the elites. These frustrations reflect a further generational schism: 60 percent of Iran’s population of 80 million is under the age of 35, while its political and religious leadership has an average age of 70.

A friend of mine lives in Tehran and was herself a prisoner in the first years of the Islamic Republic for protesting against mandatory hijab laws. In one of our first texts after the protests began, she wrote, “This government is out of touch with the people and has been for so long.” When she had internet service, she would give me brief reports about what she was witnessing. After every conversation, she let me know she’d be deleting our texts. “They are watching us,” she wrote. “If they ever get ahold of my phone . . .” I know what this means. So I would download anything she sent me or take screenshots of her messages. Yet she continued to send me footage of people in the streets chanting and women removing their headscarves.

On October 6, the Basij (one of Iran’s brutal police militias that reinforce the religious ideology of the state) invaded Sharif University (considered the most prestigious of all Iran’s universities) and cornered students in the parking lot, beating and arresting many of them. The next day, my friend messaged: “Professors of Sharif are gathering to condemn what they (the police) have done to their students. People are planning to go out. We are planning strikes. We have tried every other possible way. We tried voting, even when there were few acceptable candidates. The next time there were fewer people nominated. We tried to make reforms. Corruption is a huge barrier to achieving any results. We have tried dialogue. They do not listen. They think this country is theirs. They have imprisoned us. This land belongs to the people who live in it.”

What my friend is saying is that over the four decades of her adult life, she has witnessed many attempts to effect change, for citizens to participate in civil society in Iran, and it has amounted to little. We previously corresponded in 2009, during the major protests that grew out of the election fraud that was associated with the reelection of the president, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. She was hopeful then, but those protests were met with a violent crackdown that led to thousands of young people being arrested, sentenced to prison, or executed. At each juncture, peaceful protest has been met with state violence. The net effect is a form of continual humiliation of the Iranian people at the hands of their government and a hopelessness that has suffocated the dreams of young people. It is the frustration of this combination of lack of freedom and constant humiliation that has led to the protests.

Bay Area Iranian-American muralist and painter Farnaz Zabetian works on a mural for “Woman. Life. Freedom.” on the corner of Masonic and Solano Avenue in Albany

The paltry news coverage in the West cannot be solely blamed on the lack of internet access inside Iran, which makes it difficult to communicate and receive news footage. The way Iran has been viewed in the West is through the tired and stale dynamic of US-Iran relations, whereby Iran — the culture, the people, and even its art — is conflated with its government. Similarly, the driving engine behind most representations of Iran in the US media have been foreign policy initiatives that are designed to punish the Iranian government, but instead punish the Iranian people.

Through social media, we continually try to find news about Iran and keep it in the consciousness of the American people. The effort to shine a light on the protests have been amplified by many individuals, organizations, artists inside Iran and within the Iranian diaspora, and even outside of Iranian communities. The role of art in keeping these protests alive and visible is worth noting, particularly in the absence of on-the-ground journalism or substantive analysis in the US media.

Muralist Farnaz Zabetian paints a mural in Clarion Alley in San Francisco

Thousands of Iranians — both inside and outside Iran — have been producing art that speaks to this moment and the significance of the slogan that emerged in response to Mahsa Jina Amini’s death: “WOMAN. LIFE. FREEDOM.” Art has spoken to this moment in the proliferation of images found in graffiti on walls in Tehran; posters; memes; art installations here locally; and murals across cities and towns in the United States, Europe, and beyond. These images are not only found in physical spaces but also on social media. Protests are being staged by young people in courageous acts of resistance: in the cutting of hair, in removing headscarves in front of images of the Supreme Leader, and in singing of the informal anthem of this protest movement, Baraye (translated as “for”).

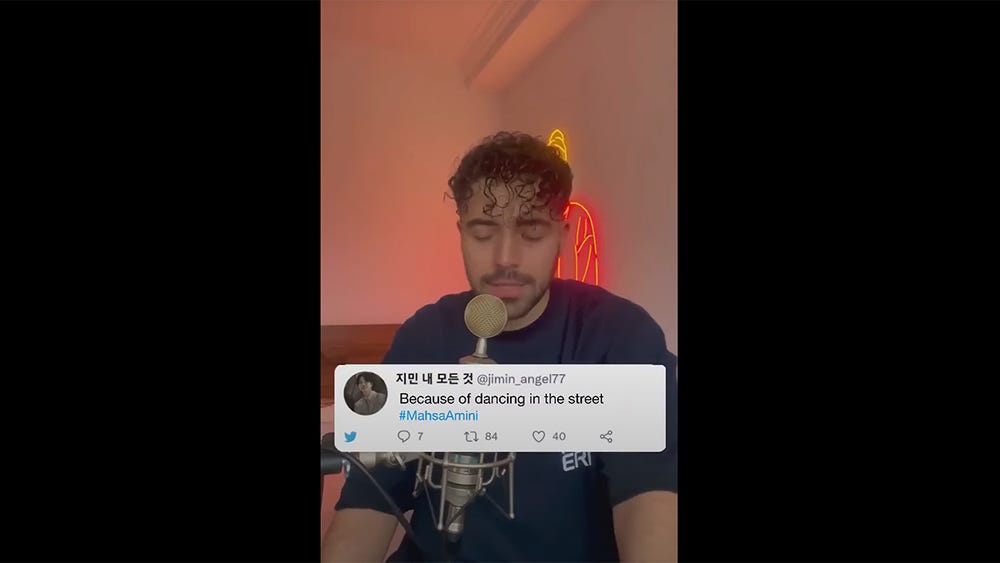

Shervin Hajipour – Baraye

The anthem was composed by the young singer-songwriter Shervin Hajipour in the early days after Mahsa Amini’s death from tweets he got in response to the prompt “why do we protest”? Hajipour was arrested and is out on bail. The song has received more than 95,000 submissions for a Grammy nomination, has been viewed by millions, and has been sung regularly at protests around the world.

The unfettered and urgent response for change, is echoed in the small gestures of joy, release, and defiance being led by brave women and girls, and now their male peers and friends but also those who are older — parents, religious people, and workers. It is a moment of inspiration and admiration for their courage but also a moment for us to watch and learn, and also remember that we have our own struggles for women’s bodily autonomy and the rights of marginalized and oppressed people right here in our country. And, like my friend in Tehran, I am trying to remain hopeful. On October 9, one of the only text messages I received from my friend in weeks, she wrote, “We are very hopeful. This time feels different. I can sense it in the air. Your support from all over the world is a great help. We won’t give up. You don’t give up. Your support is a great help to us.” I will try not only to keep hope for the Iranian people but also to keep them on the minds of my fellow citizens in this country.

Text by Persis Karim, director, Center for Iranian Diaspora Studies, San Francisco State University. In 2017, she collaborated with the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco on “Teaching Art of the Middle East and the Islamic World: An Art Education Conference.”

Photographs courtesy of Persis Karim.