Never has the ritual of washing our hands been more critical than today, as we battle the Coronavirus pandemic. Washing our hands can be a pleasurable experience, involving warm water, fragrant soap, and a soft towel, and it leaves us with a satisfying feeling of cleanliness. More importantly, it is one of the few measures we possess to prevent infection—it is a means of shedding pathogens, of removing from the skin’s surface contaminants acquired in the perilous world we inhabit.

It was only during the mid-nineteenth century that hand hygiene, advocated by Hungarian physician Ignaz Semmelweis (1818–1865) and British nurse Florence Nightingale (1820–1910), became standard practice in medical settings. Bacteria were not identified as agents of disease until the 1880s, and viruses were not discovered until the 1890s. But long before hand washing was advocated by the medical profession, it had been an element of cultures throughout the world for centuries.

Aquamanile (ewer), Hildesheim, Germany, ca. 1250–1300. Bronze, 9 5/8 x 8 3/8 x 4 in. (24.4 x 21.3 x 10.2 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Purchased with funds from various donors, 54.22

In 1954, the Legion of Honor acquired a curious bronze vessel called an aquamanile. Made between 1250 and 1300 in what is today Germany, the Legion of Honor’s aquamanile, or ewer, is fashioned in the shape of a lion, its elongated tail functioning as a handle and its mouth as a spout. An aquamanile (plural: aquamanilia) is a vessel that was used for pouring water during hand washing in both spiritual and secular contexts during the late Middle Ages. Its name derives from the Latin words for “water” and “hand” (aqua and manus). Aquamanilia were primarily employed by clerics while administering the mass, but they also adorned the tables of the wealthy during banquets.

The origins of aquamanilia can be traced back to eighth-century Iran and, indeed, ritual washing or ablution holds great significance in each of the Abrahamic religions—Judaism, Islam, and Christianity—as a means of achieving physical and spiritual cleanliness.

Although aquamanilia first appeared in Iran during the Early Abbasid period (ca. 750–861), ritual hand washing in the Abrahamic tradition can be traced back to ancient Jewish practices. Various Jewish texts prescribe hand washing as a means of spiritual cleansing. The Babylonian Talmud (ca. 500), a text that interprets the Torah (the Old Testament) and expounds Jewish law (halakha), requires hand washing prior to eating bread, a ritual called netilat yadayim. Water is first poured over one hand and then the other (the number of repetitions varies), often using a special two-handled cup called a natla. Because one hand is purified before the other, the cup’s second handle removes the need for both hands to touch as the cup passes between them. A blessing is also recited: “blessed are You, Lord our God, King of the Universe, who has sanctified us with Your commandments, and commanded us concerning the washing of the hands.” The Talmud and other texts also mandate hand washing after eating, upon waking, prior to worship, and prior to reciting blessings during worship. Historic examples of natla cups are rare, and there is likely no kinship between them and aquamanilia, but the Jewish association between washing and spiritual purity recurs in both Christianity and Islam.

In the Islamic tradition, hand washing is a component of the ablution ritual wudu, in which the hands, forearms, face, head, and feet are washed or wiped with water. The Quran mandates wudu prior to worship: “O you who believe! When you stand up for ritual prayer, wash your face and your hands up to the elbows, and wipe a part of your head and your feet up to the ankles” (5:6). The ritual’s finer points are elaborated in hadith, or accounts of the Prophet Muhammad’s teachings, including when wudu is required, how to wash each body part and in what order, acceptable sources of water, and the conditions that subsequently nullify the purity of wudu. Many mosques contain wudu facilities, ranging from a fountain to a row of faucets.

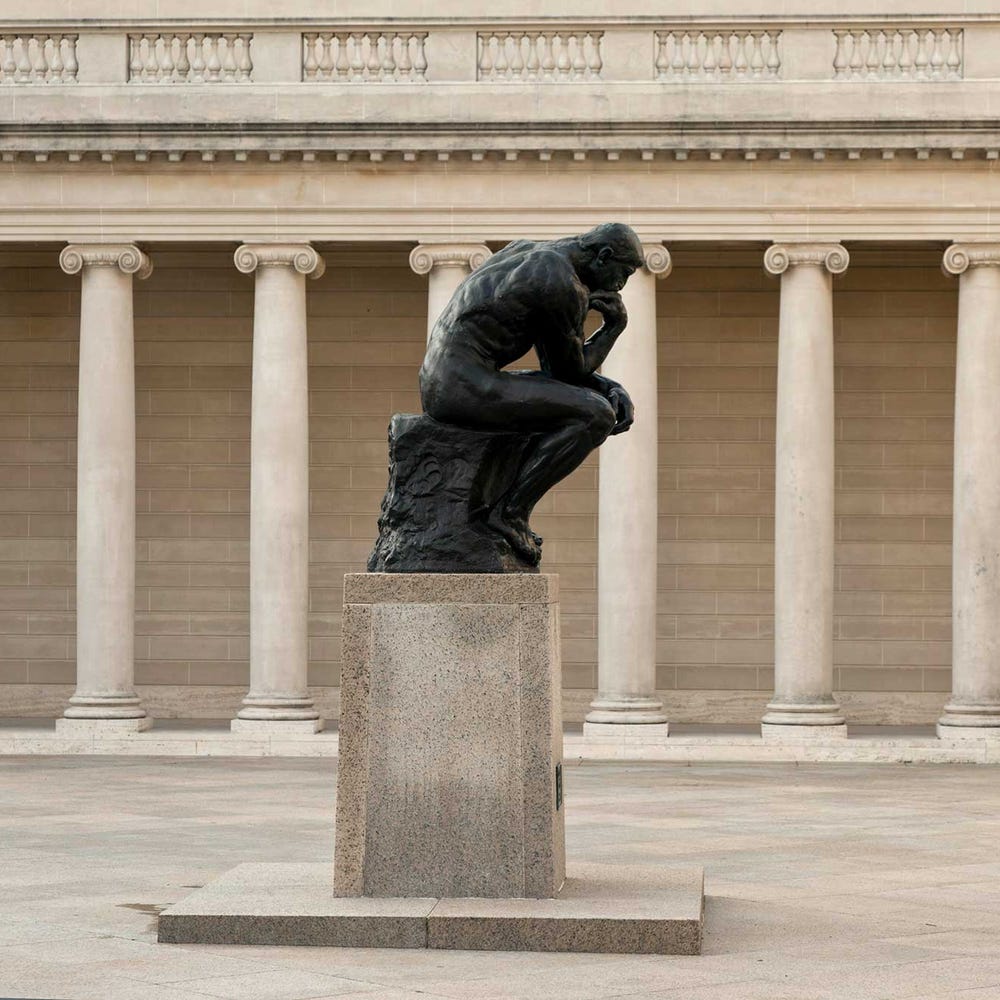

Aquamanile Shaped like an Eagle, Iraq (?), ca. 796-797. Bronze (brass), silver and copper, h. 15 in. (38 cm). State Hermitage Museum, ИР-1567

It is unclear whether aquamanilia were originally devised for religious ablution, but they are among the earliest surviving works of bronze produced in the Middle East following the advent of Islam in the seventh century. Displaying exceptionally refined metalwork for that period, aquamanilia were often commissioned by individuals as a symbol of their wealth. The oldest precisely dated example (above), probably made in Iraq or Syria in 796 or 797 and now in the collection of the State Hermitage Museum in Russia, bears the inscription “In the name of Allah the All-Merciful, the Mercy-Giving. Blessings [from] Allah. This was made by Suleiman in the city of…in the year one hundred and eighty” (796/797 AD). Although the name of the city has not been deciphered, this devout dedication suggests a possible religious function. The aquamanile is in the shape of a standing eagle, its body inlaid with silver in a lobed pattern recalling feathers. The eagle form could likewise denote an association with Islam, as the flag flown by the Prophet Muhammad during his campaigns, the ‘Black Standard’ (ar-rāyat as-sawda), was also referred to as the ‘the Eagle’ (al-uqāb). This interpretation is far from conclusive, but argues that parallel religious significance between Islamic and European aquamanilia is possible. Regardless of their function, aquamanilia produced in the shape of animals in the Muslim world declined around the thirteenth century, probably due to Islam’s proscription of imagery.

Aquamanile in the shape of a dove, Iran, ca. 1101-1300. Bronze,10 1/4 x 3 1/4 x 8 in. (27.4 x 8.4 x 20.3 cm). National Archaeological Museum, Madrid, INV.2005-72-1

During the eleventh century, trade via the Silk Road introduced the aquamanile to Western Europe, where it assumed clearer religious and secular functions. Imported Islamic aquamanilia were sometimes repurposed for Christian worship, as is thought to be the case for a dove-shaped Iranian example (ca. 1100–1300) in the National Archaeological Museum of Madrid (above), superimposed with a twelfth-century Latin inscription: ‘He was sacrificed and died’. Europeans also began to make aquamanilia, and the Mosan region (spanning modern Germany and Belgium) became a major center of production. Aquamanilia were used by clerics to pour water during a ritual called lavabo, in which the hands are washed three times: prior to donning clerical vestments, prior to administering the eucharist during mass, and after the conclusion of mass. Lavabo can also describe a set of objects used to perform the eponymous ritual, typically an ewer and a basin, of which an aquamanile would have been a part. Just as mosques are equipped with wudu facilities, some churches are endowed with a lavabo niche to house these objects, or with a fountain called a cantharus.

As in Judaism and Islam, an association between washing and spiritual purity is deeply rooted in Christianity. Perhaps the most significant expression of Christian ablution is the sacrament of baptism. Based on the gospels’ accounts of Christ’s submersion in the River Jordan by his cousin, Saint John, baptism is a ritual by which inherent, or “original” sin is washed away with water. However, aquamanilia do not seem to have figured in baptism; rather, a fixed basin called a baptismal font was used. Concerning hand washing more specifically, the term ‘lavabo’ is derived from the Latin translation of psalm 26, verse 6: ‘I shall wash (lavabo) my hands in innocency; so will I compass Thine altar, O Lord’.

Aquamanilia were also used for washing hands before and after feasts and to adorn aristocratic tables. Unlike the aforementioned Jewish ritual of netilat yadayim, hand washing in this context would have been a social custom rather than a religious act. The intended use of the Legion of Honor’s aquamanile is unknown, but its lion form corresponds to both spiritual and secular iconography. Mosan aquamanilia were produced in a variety of animal forms and, more rarely, human shapes, but lions were overwhelmingly popular. Lions appear in a few Biblical narratives, such as that of Samson slaying a lion (Judges) and that of Daniel surviving a night in a lions’ den (Daniel). The Book of Revelations refers to Christ as the ‘Lion of the tribe of Judah’ (5:5) and the lion is an enduring symbol of God in both Jewish and Christian traditions. Lions also figured prominently in Medieval secular culture. Bestiaries, books listing real and fantastical animals and their qualities, attributed courage, strength, and nobility to lions, rendering them a popular choice for heraldic imagery. In the context of a banquet, the Legion’s aquamanile could have signified the power and status of its owner. With the advent of the Renaissance in the fifteenth century, animal-shaped aquamanilia gave way to more elaborately ornamented vessels derived from Classical forms, but the ritual of lavabo and the use of ewers during banquets continued.

Lions (detail) in the Northumberland Bestiary, England, ca. 1250-60. Pen-and-ink drawing with translucent washes on parchment, 8 1/4 x 6 3/16 in. (21 x 15.7 cm). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 100, fol 8

The ritual of ablution is not exclusive to Abrahamic cultures. In the Hindu tradition, immersion in a sacred river, especially the Ganges in India, washes away impurity, and the entrances to Japanese Buddhist temples and tea gardens typically feature a stone washbasin (tsukubai) fed by a bamboo spout (kakei), with a ladle for scooping and pouring water over the hands. Aquamanilia were transported by Portuguese traders to West Africa during the fifteenth century. A leopard-shaped bronze example (below) from the eighteenth-century Kingdom of Benin (today southern Nigeria) and now in the Minneapolis Museum of Art, is thought to have been used by kings, or obas, for hand-washing ceremonies. Aquamanilia were even incorporated into local beliefs: In the fifteenth-century, King Ewuare of Benin was believed to have received aquamanilia from the sea god Olokun in his underwater palace.

Water pitcher, Nigeria, 18th century. Bronze, 17 x 26 in. (43.18 x 66.04 cm). Minneapolis Institute of Art, The Miscellaneous Works of Art Purchase Fund, 58.9

The Legion of Honor’s aquamanile offers a window into the long and diverse history of hand washing as an aspect of religious and social conduct in Abrahamic cultures and throughout much of the world. The ewer is on view in the Legion of Honor’s newly reinstalled Gallery 2 alongside other medieval treasures. It serves as a reminder that, each time we wash our hands, we are not only preventing disease but also sharing in a culturally significant human tradition.

Text by Thomas Wu, curatorial assistant, European Decorative Arts & Sculpture, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.