James Tissot: Fashion + Faith is the first major reassessment of Tissot’s career in over 20 years. New scholarship on the artist presented in this international retrospective, co-organized with the Musée d’Orsay, and the accompanying monographic publication demonstrate that even Tissot’s most fanciful society paintings reveal rich and complex commentary on topics such as 19th-century society, religion, fashion, and politics. Below is an excerpt from the exhibition catalogue, by exhibition curator Melissa Buron, which chronicles how Tissot became interested in séances and spiritualism following the death of his muse Kathleen Newton.

Holyday (The Picnic), ca. 1876. Oil on canvas, 30 x 39 in. (76.2 x 99.4 cm). Tate, N04413. © Tate, London 2019

The name James Tissot evokes depictions of fashionably dressed women and debonair men, images that seem to celebrate materiality over spirituality, yet Tissot’s most personally meaningful work was as a visionary religious artist.

Raised and educated in the Roman Catholic tradition, Tissot expressed a renewed interest in the religion as well as in Spiritualism following the death of his companion and muse, Kathleen Newton, in 1882. Spiritualism and its French counterpart, Spiritism, were complex socio-religious belief systems popular in the late 19th century that attempted to scientifically prove the existence of the afterlife. Spiritualism looked beyond Judeo-Christian concepts of the hereafter by conducting rituals such as séances and presenting “evidence” of direct communication between the living and the dead, such as table rapping and slate writing.

Summer Evening, 1881–1882. also known as The Dreamer. Oil on wood panel, 13 3/4 × 23 3/4 in. (34.9 × 60.3 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris, Bequest of William Vaughan, 1919, RF 2254. © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY

Newton died in London on November 9, 1882. It is not clear how long Newton had suffered from tuberculosis — also called consumption because it seemed to consume the invalid’s body — but witnessing her decline surely distressed Tissot. Newton’s niece, Lilian Hervey recalled that afterward, a bereaved Tissot “draped her coffin in purple velvet and prayed beside it for hours.” After Newton’s funeral, Tissot abandoned the London home they shared together, returned to Paris, and began attending Spiritualist séances in an attempt to make contact with her. According to the artist Louise Jopling, it was Newton’s death that stimulated Tissot’s Spiritualist interests:

At one time James Tissot was very hospitable, and delightful were the dinners he gave. But these ceased when he became absorbed in a grande passion. . . . After her death, he came across some spiritualists, who easily persuaded him that he could get into communication with his chère amie. He used to hold séances every afternoon, after his day’s work was over.

On May 20, 1885, Tissot attended a private séance in London, facilitated by the British medium William Eglinton. At this séance, Eglinton purportedly materialized the deceased Newton along with the medium’s spirit guide. According to Eglinton:

The figure of the One, lost and loved, appearing so distinctly as to be recognised not only by all the sitters present from her portraits . . . but by M. Tissot himself; and so much was this beyond question that he instantly transferred the whole scene to canvas, that he might retain it in his memory . . . all is shown as it happened, neither more nor less . . . a monument to the abiding truths of Spiritualism, and of the genius of one of its latest converts.

The Apparition (detail), 1885. Oil on canvas, 29 1/8 × 21 1/4 in. (74 × 54 cm). Private collection

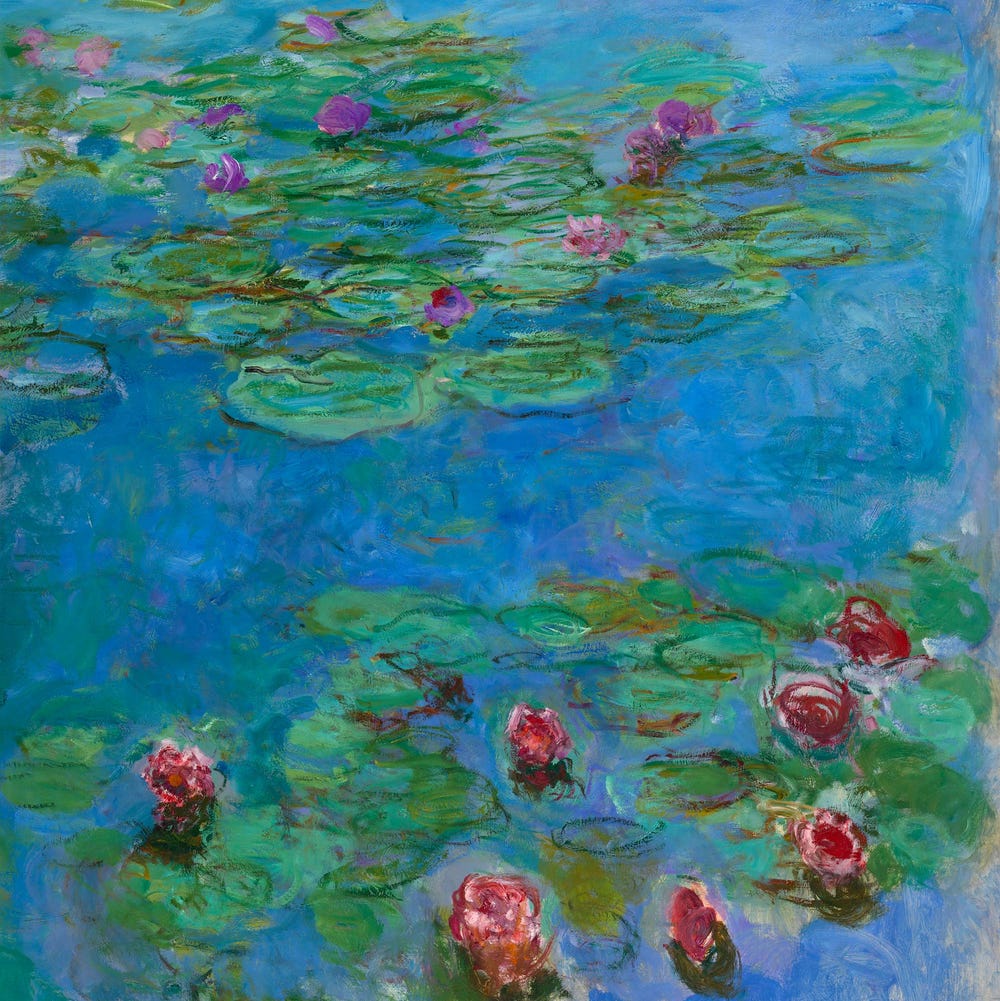

The work that Eglinton refers to, the 1885 oil painting The Apparition (also known as The Mediumistic Apparition), re-creates this mysterious event. The representation of glowing spirits wrapped in shroud-like garments anticipates the mystical themes and motifs of Tissot’s forthcoming biblical illustrations.

Contemporary accounts reveal that Tissot eagerly shared The Apparition with visitors, including Georges Bastard, one of his earliest biographers. Bastard describes “electric rays” emitting from the composition’s figures. Goncourt also reported seeing the work in a room where Tissot performed rituals:

In the dusk, refusing to look for candles, with a voice which he made mysterious and a vague gaze, he showed us a crystal bowl and an enamel panel, which served at his conjurings . . . He took up a convenient notebook, where he showed us entire pages containing the history of his conjurings, and he finally showed us a picture representing a woman with luminous hands, whom he said had come to embrace him.

Panel with theosophical symbols, 1888. Cloisonné enamel on copper, 6 3/4 × 16 1/2 in. (17 × 42 cm). Private collection

The panel that Goncourt describes may be a recently rediscovered cloisonné enamel made by Tissot that conflates Egyptian, Christian, and Chinese symbolism relating to the afterlife, demonstrating Tissot’s knowledge of international and historical spiritual iconography. Each of the panel’s corners features the symbol of one of the four Christian Evangelists. The standing winged protectors of the dead are the Egyptian goddesses Nephthys and Isis, sisters of Osiris; the central figure is their mother, Nut, goddess of the sky, who often appeared on Egyptian coffins. Tissot rendered the disk above Nut’s head as the ancient Chinese yin and yang symbol, enhanced with his own monogram, “JTJ.” This combination of diverse symbols reflects the late 19th-century European interest in alternative spiritualities, which borrowed concepts as well as iconography from a variety of belief systems.

Volumes documenting the proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research found after Tissot’s death at his estate, the Château de Buillon, confirm his sustained curiosity about Spiritualism and the occult. A newspaper report covering the 1964 sale of Tissot’s possessions described a collection of five thousand books, including publications demonstrating that Tissot:

Had a weakness for ectoplasms, turntables, esotericism and spiritualism. Several hundreds of volumes are collected dealing with these subjects. . . . One feels that James Tissot had brought back from his long stay in England a taste . . . for . . . ghosts haunting the romantic castles.

Portrait of the Pilgrim, 1886–1896. Opaque watercolor over graphite on gray wove paper, 9 1/16 x 5 5/8 in. (23 x 14.3 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Thomas E. Kirby, 06.39

Text by Melissa Buron, director of the art division at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. Excerpted from James Tissot, edited by Buron, and published by the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco in association with DelMonico Books • Prestel.

Learn more about James Tissot: Fashion + Faith.

Further reading

- Georges Bastard. “Nos Peintres. James Tissot. Notes intimes.” Revue de Bretagne et de Vendée, 2nd series, no. 36 (November 1906): 253–278.

- William Eglinton. “The ‘Apparition Mediunimique.’” The Medium and Daybreak 17, no. 831 (March 5, 1886): 153.

- John Stephen Farmer. ’Twixt Two Worlds: A Narrative of the Life and Work of William Eglinton. 2nd ed. London: E. W. Allen, 1890.

- Edmond and Jules de Goncourt. Journal: Mémoires de la vie littéraire. 3 vols. Edited by Robert Ricatte. Paris: Robert Laffont, 1959.

- Louise Jopling. Twenty Years of My Life, 1867–1887. London: John Lane The Bodley Head Limited, 1925.

- John Warner Monroe. Laboratories of Faith: Mesmerism, Spiritism, and Occultism in Modern France. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2008.

- J. Vartier. “Derniers ‘meubles’ à quitter le château de Buillon. Les 5,000 volumes de la bibliothèque de James Tissot.” Unknown publication, ca. 1964.