A Legacy of Illumination: Medieval Manuscripts at the Time of the Pre-Raphaelites

By Bryan C. Keene

September 7, 2018

The shimmer of gold and the brightly colored pages of medieval handmade books inspired some of the most creative artists in Britain in the late nineteenth century. Six illuminated manuscripts (so called because they were often embellished with gold or silver leaf), on loan from the renowned J. Paul Getty Museum collection and included in the exhibition Truth & Beauty: The Pre-Raphaelites and the Old Masters (on view at the Legion of Honor through September 30), give us a luminous glimpse into this connection that spanned centuries.

The Annunciation, Master of the Llangattock Hours and Willem Vrelant, in the Llangattock Hours, Ghent-Bruges, Belgium, 1450s. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Ms. Ludwig IX 7 (83.ML.103), fol. 53v

Although the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, founded in 1848, was better known for its affinities with artists of the Italian Renaissance, their principles equally drew from fifteenth-century Netherlandish painting, including the Annunciation (1434–1436), by Jan van Eyck (ca. 1390–1441). In this work, Van Eyck depicted an archangel visiting the Virgin Mary to tell her she will bear the son of God, an event similarly pictured in the illuminated manuscript Llangattock Hours (ca. 1450).

Mariana, John Everett Millais, 1851. Oil on panel. Tate, London, accepted by HM Government in lieu of tax and allocated to the Tate Gallery, 1999, T)7533

Though its subject is secular, the 1851 painting Mariana, by Pre-Raphaelite cofounder and artist Sir John Everett Millais (1829–1896), aesthetically echoes these two earlier works. Inspired by the character from Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure, Millais’s Mariana wears a dress in the same vivid blue as Mary’s. Standing with her back arched above a work table, she emits a solitude as palpable as the divine presence by the Virgin’s side. Mariana’s chamber features a Gothicizing stained-glass window that depicts The Annunciation, while the draped cloth on the table and painted walls recall the floral borders of the Getty’s Llangattock Hours. This new medievalism, as scholars refer to it, was in vogue at the time of Millais’s painting.

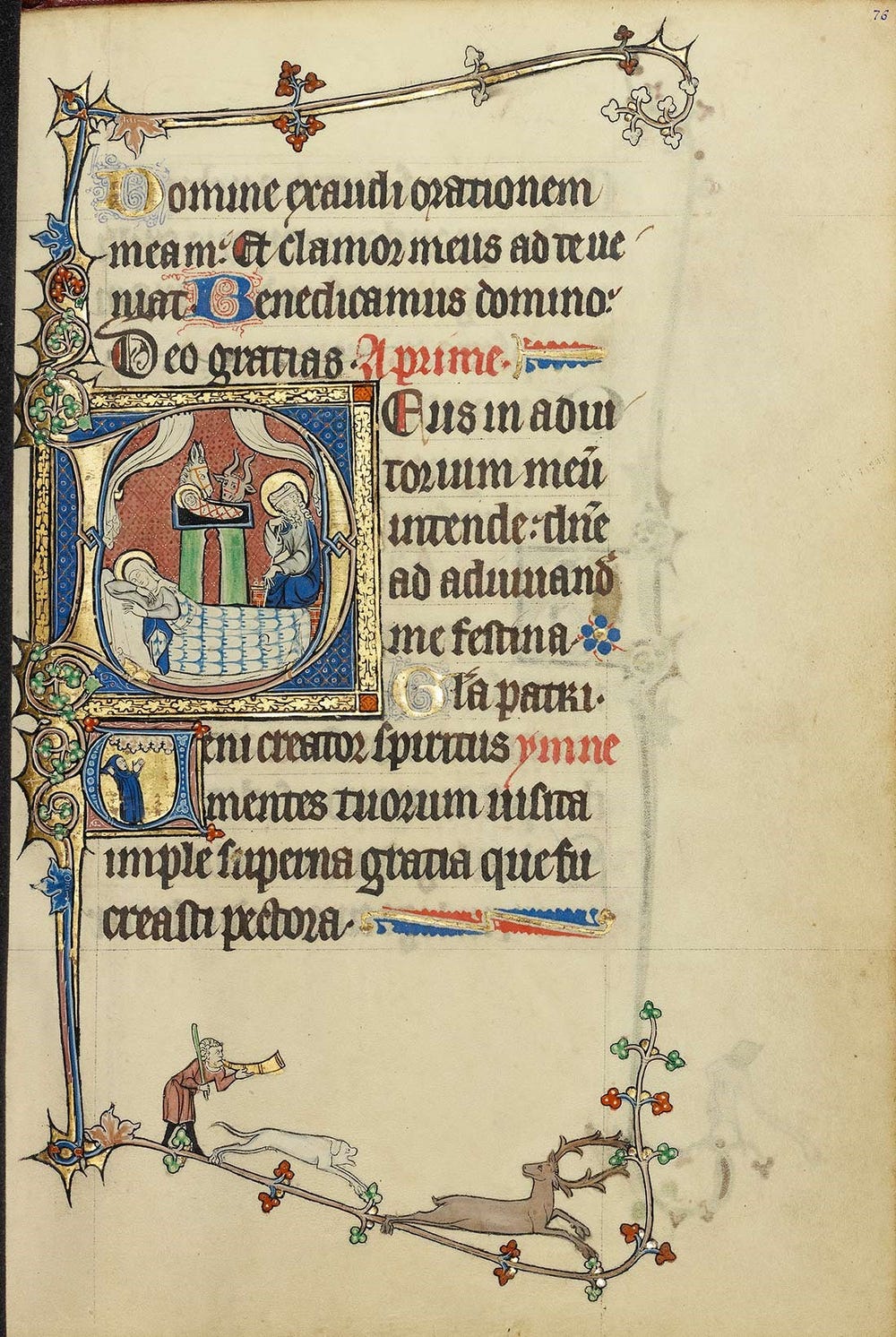

Initial D: The Nativity; Initial V: A Monk in Prayer from the Ruskin Hours, French, about 1300. Tempera colors, gold leaf, and ink on parchment, 10 1/8 x 7 1/16 in. (26.4 x 18.3 cm). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Ms. Ludwig IX 3 (83.ML.99), fol. 76

Living during a period of great mass production, Victorian art critic and collector John Ruskin (1819–1900) turned to the Middle Ages for inspiration. An influence on and champion of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, Ruskin once owned an early fourteenth-century French book of hours filled with delicately painted narrative scenes from the lives of Christ and the Virgin Mary. The manuscript now bears his name as the Ruskin Hours.

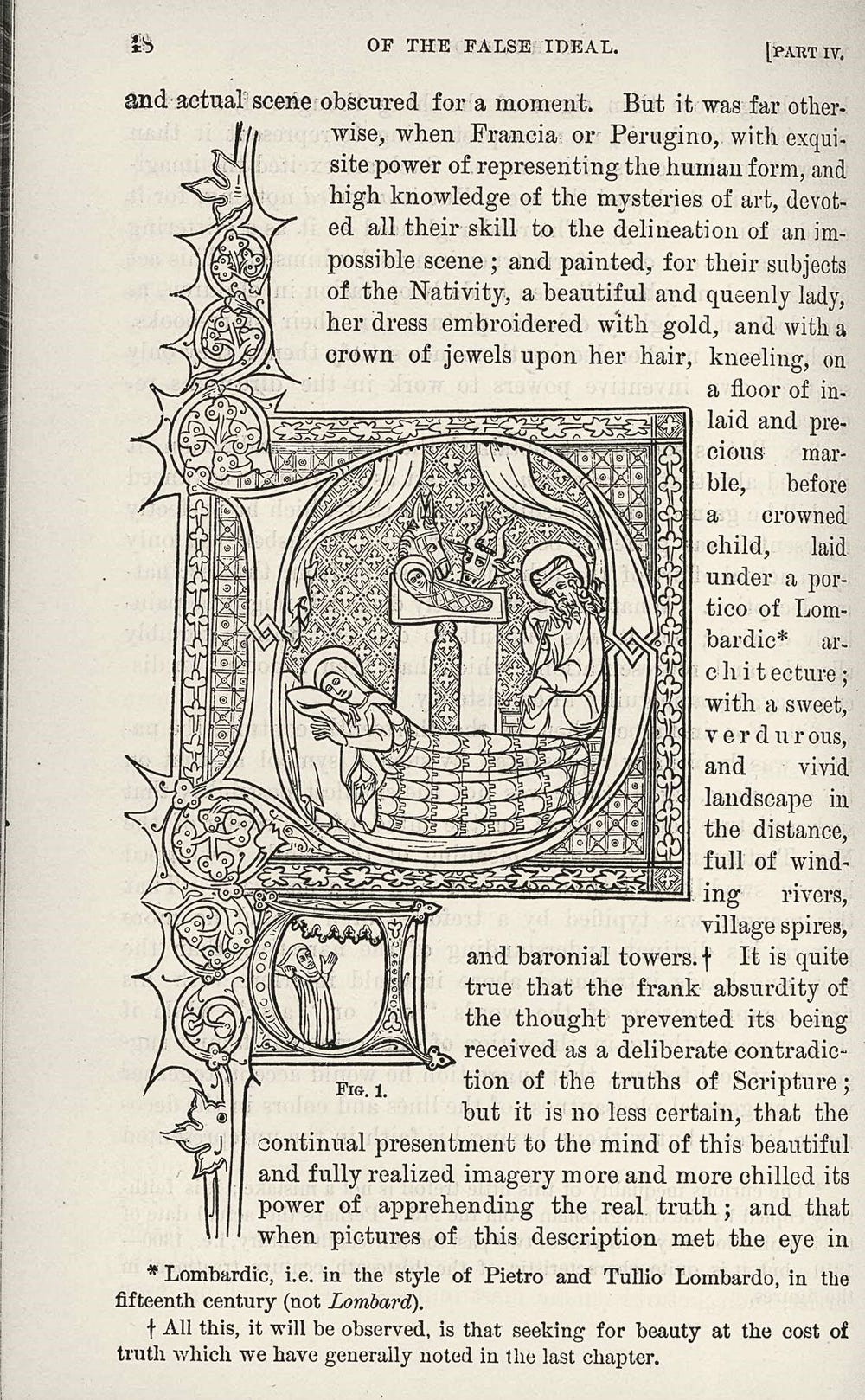

Of the False Ideal, in John Ruskin’s Modern Painters, vol. 3, pp. 52-53. The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, ND1135.R8 1903

Ruskin used an image of The Nativity from this medieval devotional manuscript (above left) to illustrate the third volume of Modern Painters (1843–1860). In the five-volume book, Ruskin praised the skill, imagination, and clear narratives of early medieval and Renaissance painting while celebrating the tempera revival of the Pre-Raphaelites and the carefully observed paintings of J. M. W. Turner.

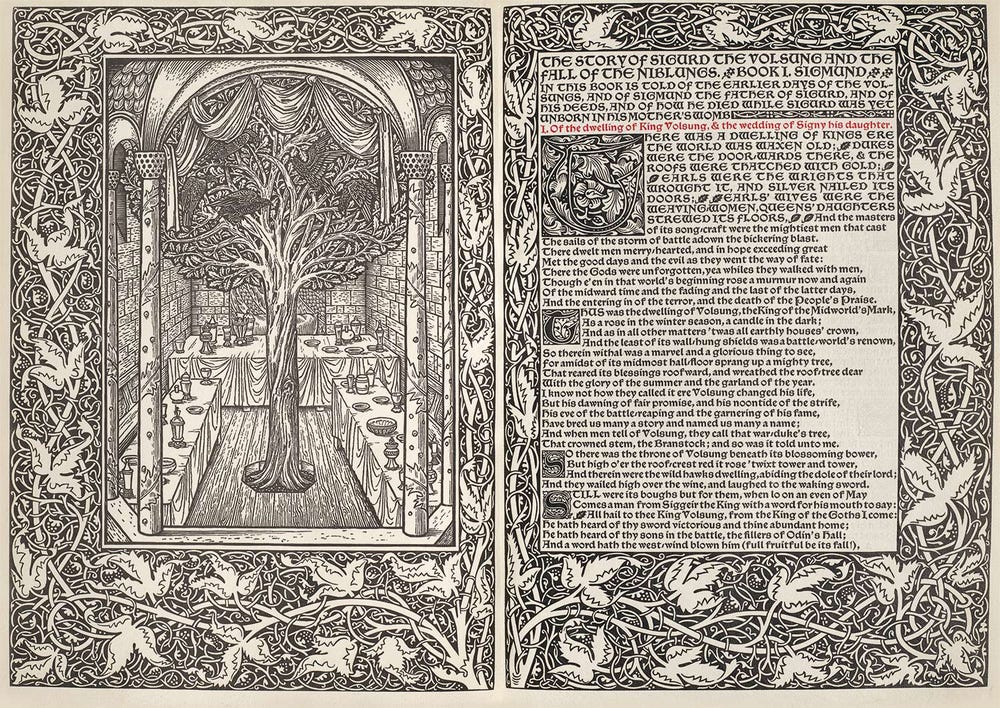

Page from The Story of Sigurd the Volsung and the Fall of the Niblungs, illustration by Edward Burne-Jones with border decoration by William Morris, printed by William Morris at Kelmscott Press, Hammersmith. Woodcut, 12 ¼ x 9 ¼ in. (32.5 x 23.5 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Achenbach Foundation for Graphic Arts, Gift of the Reva and David Logan Foundation, 1998.40.109.1-2

The second-generation Pre-Raphaelite William Morris (1834–1896) often collaborated on his projects with artists Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828–1882), Edward Burne-Jones (1833–1898), and William Harcourt Hooper (1834–1912). The latter two produced the engravings for Morris’s The Story of Sigurd the Volsung and the Fall of the Niblungs (1898; above). Like Ruskin, Morris collected illuminated manuscripts, including two large Bibles from France, both of which are part of the Getty collection. These works are now on view in the exhibition at the Legion of Honor, alongside medieval revival decorated books by Morris (from the collection of Ann and Gordon Getty) and stained-glass windows designed by Burne-Jones.

Leaves and Cuttings

In the nineteenth century, there was a sensation across Europe for manuscripts, as the so-called “scissor men” cut apart the pages of medieval and Renaissance books so that collectors and connoisseurs could own a piece of this brilliant past.

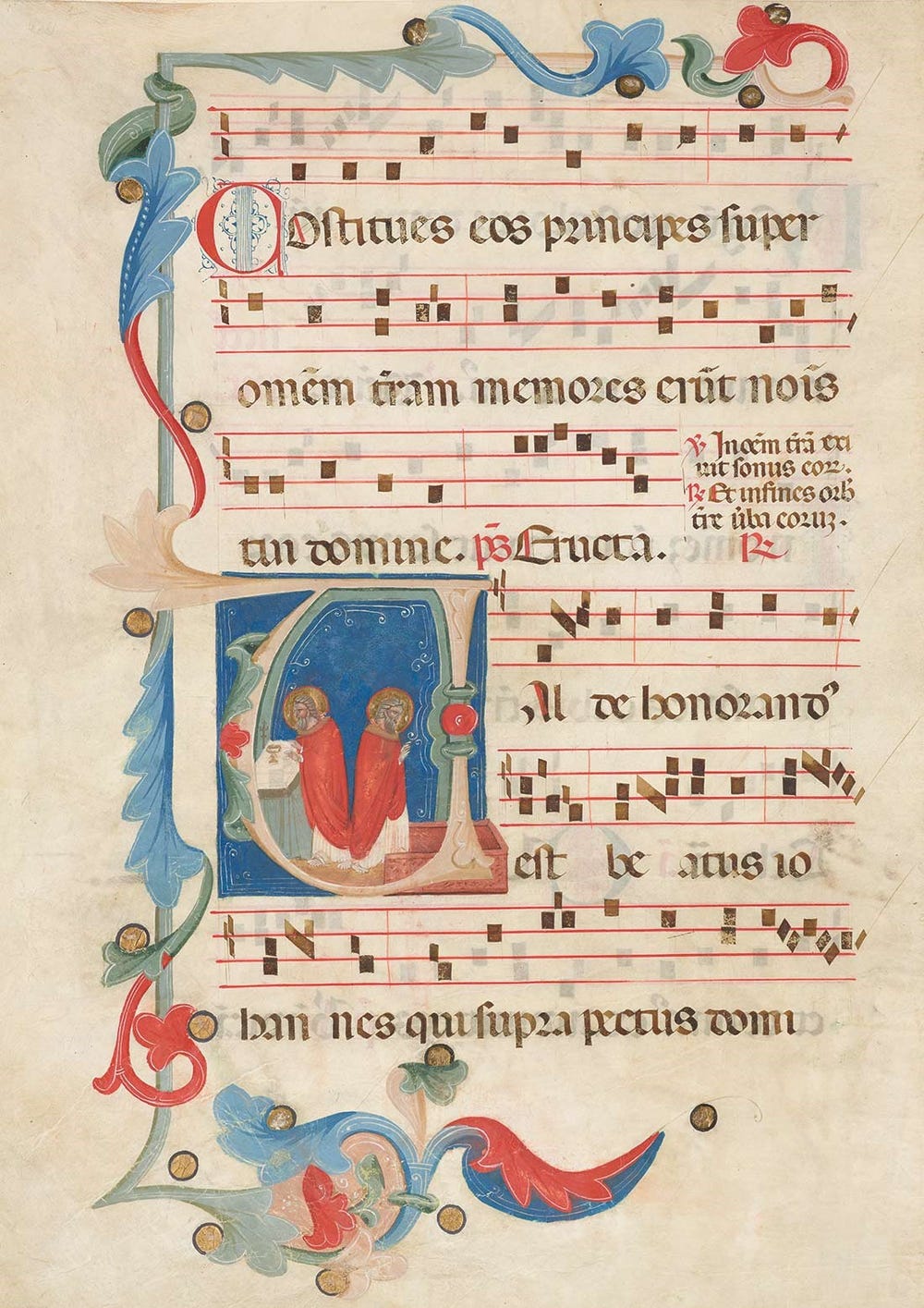

Saint John the Evangelist Celebrating Mass, Maestro del 1328 (Maestro Pietro?, formerly the Quarto Maestro di San Domenico), from a Gradual for the Church of San Domenico in Bologna, 14th century. Tempera, ink, and gold leaf on parchment, 20 ½ x 14 ¼ in. (52.1 x 37 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Joseph M. Bransten, 1959.115.2r-v

The Achenbach Foundation for Graphic Arts at the Legion of Honor includes a little-known but impressive array of such leaves and codices, including an unpublished page from a fourteenth-century Bolognese choir book, part of the Fine Arts Museums’ collection of nearly twenty-five premodern manuscripts and among the illuminated manuscripts on view in Truth and Beauty. The page was bequeathed to the Legion of Honor by collectors Joseph (1929–2001) and Renata Bransten (1933– ). Another exciting discovery among the group is a cutting from a Benedictine gradual by Don Simone Camaldolese.

Text by Bryan C. Keene, assistant curator of manuscripts at The J. Paul Getty Museum.

I am grateful to Melissa Buron, Colleen Terry, Jim Ganz, and Victoria Binder for their generosity in allowing me to study the FAMSF manuscripts.