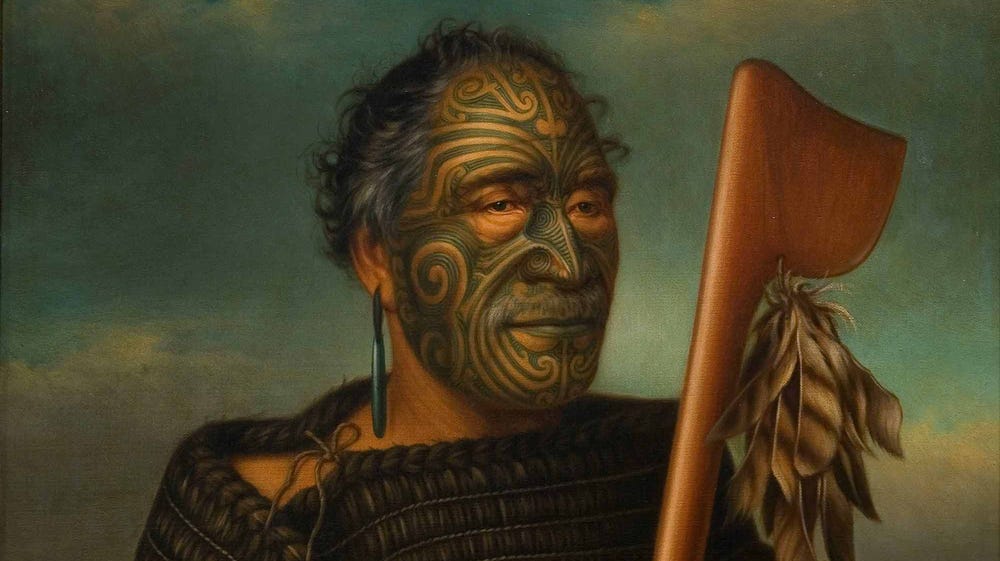

Gottfried Lindauer, Tamati Waka Nene (detail), 1890. Oil on canvas. Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, gift of Mr H E Partridge, 1915

The Māori Portraits: Gottfried Lindauer’s New Zealand

Jump to

Come face to face with the leading Māori protagonists of nineteenth-century New Zealand in a series of arresting images by the country’s most prolific portrait painter, Gottfried Lindauer. These paintings, revered embodiments of Māori ancestors, capture the fascinating personal stories of his subjects as well as the complex intercultural exchanges occurring at a time of great political, cultural and social change.

Thirty-one compelling historic portraits of Māori rangatira (men and women of esteem and rank) are on view in The Māori Portraits: Gottfried Lindauer’s New Zealand. Painted by a Bohemian-born immigrant artist who created the largest number of Māori portraits in existence, these finely detailed and powerful images pay tribute to the individuals who served their communities and the emerging country of New Zealand when colonial settlement was forging cross-cultural interactions between Māori — the indigenous people of New Zealand — and Pākehā, European settlers and their descendants. They document peacemakers and warriors, politicians and diplomats, tour guides and landholders, entrepreneurs and global traders painted between 1874 and 1903.

In depth

Gottfried Lindauer (1839 – 1926) was born in Pilsen, Bohemia (now the Czech Republic), and privately trained for the artistic profession in Vienna. He left few clues as to why he immigrated to New Zealand in 1874, but there he quickly gained popularity for his lifelike portraits and became the best-known painter of eminent Māori. Lindauer attracted clients by advertising for private commissions in local newspapers and presenting his Māori portraits in shop windows. He had several important patrons, including Henry Partridge, a businessman who commissioned more than eighty paintings and established a gallery for the display of his work; and Walter Buller, a lawyer who promoted Lindauer’s work through personal introductions. Photography was integral to Lindauer’s practice. He predominantly worked from studio photographs in addition to painting from life, and most of his Māori portraits were painted posthumously.

Lindauer’s portraits of eminent Māori were prominently displayed in private homes and marae (meeting houses) and at tangihanga (funerals), practices that continue today. The images are seen as powerful embodiments of ancestors that contain mana (prestige) of the people depicted. These Māori leaders and revered chiefs led their tribes during battles for land and resources after European settlement began, or acted in defiance or defense of the British colonial government during the New Zealand land wars of the mid-1800s. A number of them signed New Zealand’s founding document, Te Tiriti o Waitangi (Treaty of Waitangi), in 1840. These individuals were leading protagonists whose actions and influence determined the rich unfolding of colonial, political, diplomatic, mercantile, military, and spiritual life in newly established New Zealand.

Lindauer revolutionized painted portraiture in New Zealand by basing many of his representations of Māori — both living and deceased — on studio photographs. The developments within photography during the 1870s made studio portraits more affordable, and a large market developed for photographic images of Māori as tourist mementos. Such portraits also circulated internationally as part of a growing market for ethnographic photographs. The hand-sized carte de visite was an inexpensive and popular format that was easy to reproduce and transport. Lindauer collected a significant number of cartes de visite by photographers from throughout New Zealand as well as creating his own in the studio. Photographs used by Lindauer for his portraits were taken in the studios of Samuel Carnell, Foy Brothers, Elizabeth Pulman, and others. Lindauer also painted over photographs on board, calling these works “bromide” paintings, a reference to the silver bromide contained within photographic prints.

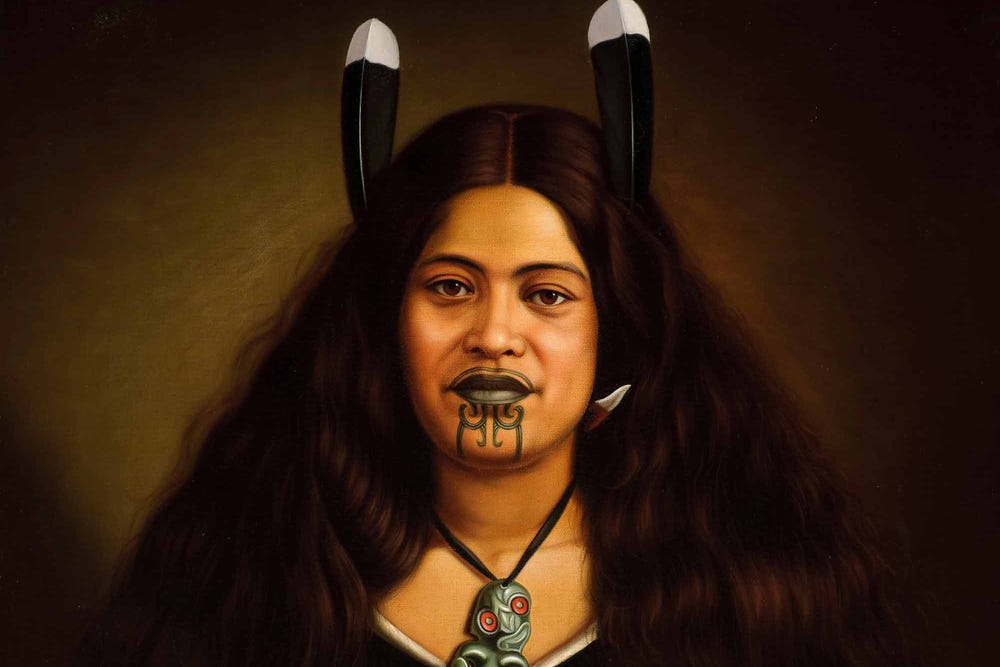

Lindauer’s paintings feature many men and women in customary Māori clothingand adornments at a time when European-style clothing and accessories were worn as daily dress by Māori and Pākehā alike. For the artist and his patrons, the portraits documented not only the prominent Māori figures but also their clothing and personal adornments signifying status, wealth, and esteem. Many of the sitters have flax kākahu (cloaks) draped around their shoulders while others are shown with prized kahu kiwi (kiwi-feather cloaks), which are worn only by those of high rank and lineage. Highly valued greenstone heitiki are worn around the neck, and huia bird feathers are in the hair. Māori clients selected what they wore and how they were represented, but in portraits painted from photographs, the artist sometimes added elements such as huia feathers or Māori clothing. He also used kākahu and taonga (treasures) as props, some of which he received as gifts.

The ultimate chiefly symbol of a Māori man is his rangi paruhi, or full-face tattoo; for women it is the moko kauae (chin tattoo) and ngutu pūrua (fully tattooed lips). Two forms of tā moko, the art of Maori tattooing, are detailed by Lindauer. In the first, designs on the face were formed by using greenstone or bone chisels to incise the skin, forming grooves for the application of ink. In the second, needles of bone (or later, metal) were used to pierce the skin and insert ink under the surface for lip and other tattoos. Lindauer took great care to accurately portray the forms of facial moko. His paintings document the range of facial tattoos at a time when the practice was key to asserting tribal identity and social status.

After a period of sustained contact between Māori and Pākehā in the late eighteenth century, the British began extracting New Zealand’s natural resources to support their colonies in Australia. Firearms were introduced to Māori chiefs as trade items in the early 1800s, and intertribal warfare to settle longstanding disputes shifted from hand-to-hand combat toward deadlier gun battles in the “musket wars.” In 1840 the Treaty of Waitangi between representatives of the British Crown and Māori chiefs was signed. The agreement, contested to this day, is the foundational document establishing New Zealand as a colony under British law and government. Native Land Courts were established and facilitated the transfer of Māori property to settlers and the Crown. In 1858, the Kīngitanga (Māori King movement) was founded with the aim of uniting Māori under a single sovereign and to resist colonial policies. Lindauer’s paintings represent Māori on all sides of these decisions and disputes.

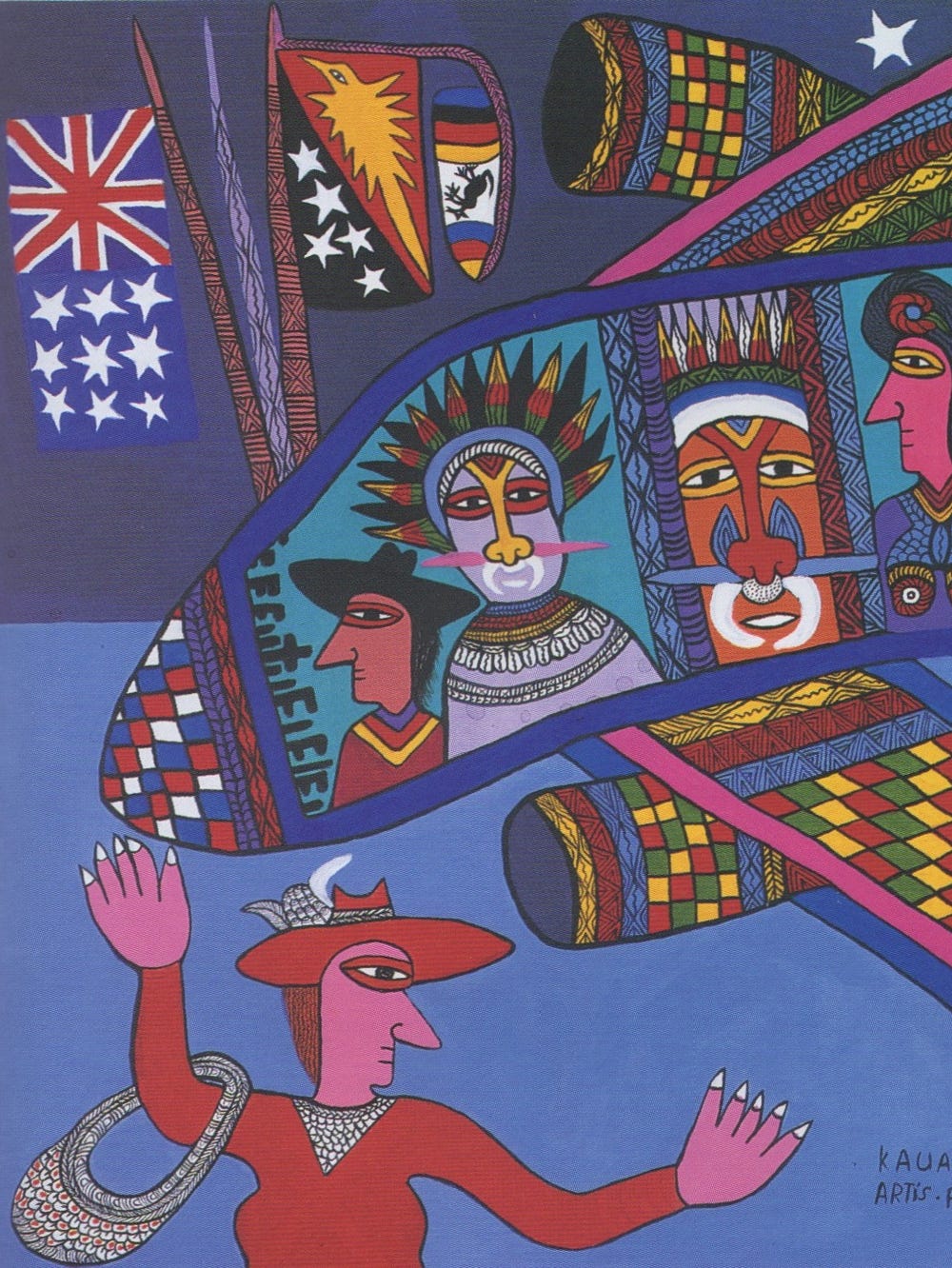

During the 1880s, Lindauer’s paintings were included in several international exhibitions showcasing New Zealand as a British colony. Displays of natural resources and commercial products were highlighted along with works of fine art and natural history specimens to show social, political, and economic development in hopes of attracting settlers and visitors. The Land Court attorney Walter Buller served as the commissioner for the 1886 Colonial and Indian Exhibition in London and showed twelve Lindauer paintings from his collection. He presented one painting to the Prince of Wales, the future King Edward VII, who admired it and subsequently rewarded Buller with the first knighthood to a citizen born in New Zealand. Along with the Lindauer portraits, Buller displayed Māori works, including a storehouse and wood carvings. Buller believed that Māori culture would not survive colonization and that the works in his collection would become important documentary remnants of the past.

In the news

Gallery

Sponsors

This exhibition is organized by Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, New Zealand, in collaboration with the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

With the support of the New Zealand Government through Manatū Taonga – Ministry for Culture and Heritage’s Cultural Diplomacy International Programme and Te Puni Kōkiri, Ministry of Māori Development

President’s Circle

Lisa Sardegna and David A. Carrillo

Curator’s Circle

The Donald L. Wyler Trust

Additional support is provided by Blossom Strong.