Victoria Dubourg and the Louvre: The Museum as School for Female Artists

By Isabella Holland

March 1, 2022

The year 1793 witnessed both the execution of King Louis XVI and the transformation of the Louvre from a palace into an art museum. In its postrevolutionary reorganization, the former royal residence offered the public access to a collection predominantly formed by the deposed Bourbons. A new generation of artists flocked to its galleries, seeking to draw inspiration and fine-tune their technical skills by studying the art of the past. For the rising number of female artists in the 19th century, the Louvre provided an alternative space to further their artistic education, as they were barred from studying at the official École des Beaux-Arts (School of Fine Arts). Victoria Dubourg Fantin-Latour (1840 – 1926), whose Still Life with Pink and White Stock, 19th or 20th century, hangs at the Legion of Honor, was among the women who secured a permit to paint directly from the masterworks at the museum.

Victoria Dubourg, Still Life with Pink and White Stock, late 19th century. Oil on canvas, 22 x 18 1/2 in. (55.9 x 47 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Gift of Mrs. Ralph K. Davies, 1975.8. Photograph by Randy Dodson

Dubourg trained privately in the studio of artist Fanny Chéron (born 1830) and established her independent practice in Paris by the early 1860s. Archival records place Dubourg at the Louvre in 1866, when she received an 800 franc commission from the Ministry of Fine Arts to execute a replica of Pietro da Cortona’s 17th-century painting Virgin and Child with Saint Martina. This assignment coincided with an extensive arts initiative undertaken during the reign of Napoleon III to expand and reorganize the Louvre’s collection. As part of the state’s oversight, the institution’s holdings were copied and sent to churches and administrative offices throughout the country. Dubourg later fulfilled a similar request to copy Titian’s Pilgrims of Emmaus, 16th or 17th century, no doubt granting her some financial independence to study and copy artworks in the Louvre’s collection for her own personal development.

The Louvre provided a gateway to art history outside the confines of a formal educational body. This proved advantageous to emerging female artists like Dubourg, who were not eligible for admission into the École des Beaux-Arts until 1897. Crucially, the museum also provided a rare forum for women — whose training was typically conducted in a very private setting — to form connections with fellow artists whom they painted alongside. In 1869 Dubourg met her future husband and collaborator, Henri Fantin-Latour (1836 – 1904), while both were copying Correggio’s The Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine of Alexandria, 1526 – 1527. Perhaps their encounter was inevitable, as both socialized with a circle of progressive artists that frequented the museum, including Édouard Manet (1832 – 1883), a guest at their 1875 nuptials, Berthe Morisot (1841 – 1895), and Edgar Degas (1834 – 1917), who painted Dubourg’s portrait, below.

Edgar Degas, Victoria Dubourg, about 1868–1869. Oil on canvas, 32 x 25 1/2 in. (81.3 x 64.8 cm). Toledo Museum of Art, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. William E. Levis, 1963.45. Image courtesy Toledo Museum of Art via Wikimedia

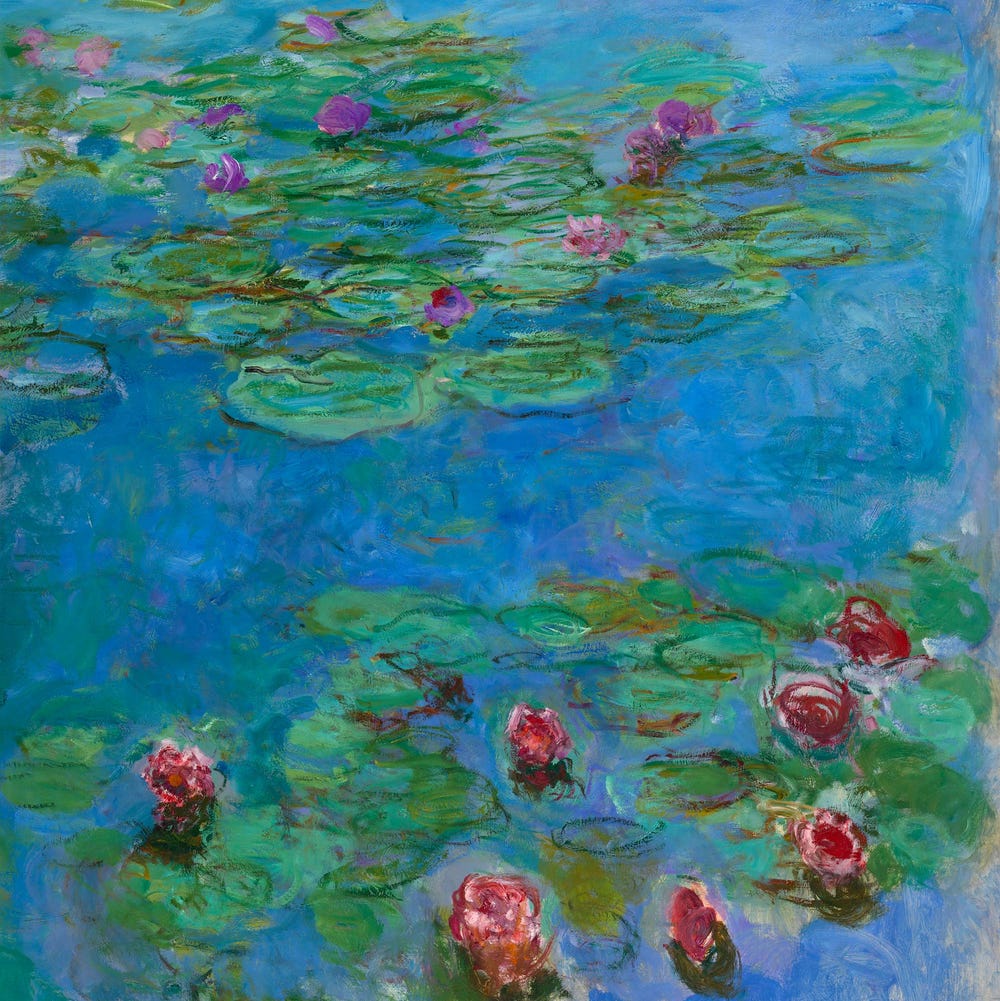

Although they shared a well-documented interest in religious painting from the Italian Renaissance, Dubourg and Fantin-Latour became some of the most dedicated practitioners of flower painting in the latter half of the 19th century. The artists’ attraction to still-life painting paralleled both the genre’s resurgence throughout the 1850s and 1860s and the Louvre’s acquisition of older paintings in this vein. Notably, the museum began to display more works by the 18th-century still-life painter Jean Baptiste Siméon Chardin, like La Brioche, 1763, which entered the collection in 1869. Dubourg’s Still Life with Pink and White Stock may offer an homage to Chardin in its simple arrangement of colorful garden flowers that emerge from a subdued brown background.

Modern study of Dubourg’s production has been somewhat limited and has often explored her biography through that of her husband, whose works Dubourg fastidiously documented in a catalogue raisonné published in 1918, seven years after Fantin’s death. They shared a studio space at 8 Rue des Beaux-Arts in Paris and together sourced fresh blooms to paint from the family estate in Buré, Normandy (which Dubourg inherited from an uncle). Though Dubourg and Fantin-Latour developed a similar style from working side by side, Dubourg signed the prodigious number of pictures she displayed at the annual Paris Salon and other international art exhibitions with her maiden name, perhaps in an effort to hold on to a discrete artistic identity.

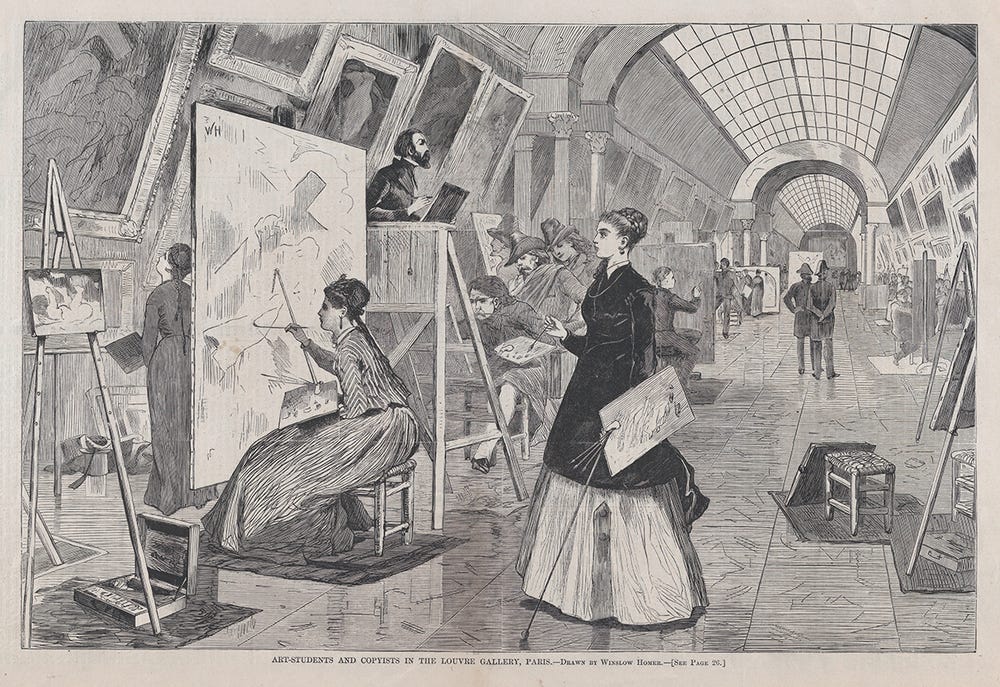

Further scholarly research could reveal more names of the women copyists and students, like Dubourg, brought to the Louvre through governmental patronage or independent study. Literature and visual material from the era certainly document them. Winslow Homer’s 1868 engraving Art Students and Copyists in the Louvre Gallery, Paris prominently features female copyists and students in front of Eugène Delacroix’s The Death of Sardanapalus, 1827. Yet despite a widening 19th-century art world, the notion of women taking up space to work prompted the ire of critics like Léon Lagrange, who disparaged the amount of “petticoats perched on the ladders” he found during a visit to the Louvre in his 1860 article “On the Rank of Women in the Arts.”

Winslow Homer, Art-Students and Copyists in the Louvre Gallery, Paris. Wood engraving, 9 1/16 x 13 3/4 in. (23 x 35 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1936, 36.13.13(1). Image courtesy the Met

Lagrange’s belittling remarks nevertheless showcase that the Louvre provided a space for female artists to be recognized publicly in their profession and a resource to further their advancement in a competitive Parisian art world. Museums of today can offer the same kind of visibility to women artists through the display of their artworks: the recent addition of Victoria Dubourg’s Still Life to the Legion of Honor’s Gallery 19 surfaces a fascinating connection between the rise of both public art museums and women artists in the 19th century.

Text by Isabella Holland, curatorial assistant, European paintings.

Want to learn more? Watch Victoria Dubourg at the Louvre: A Conversation with Curatorial Assistant Isabella Holland: