Trigger Figure: Patrick Kelly’s Reclamation of Racist Iconography

By Kibwe Chase-Marshall

December 6, 2021

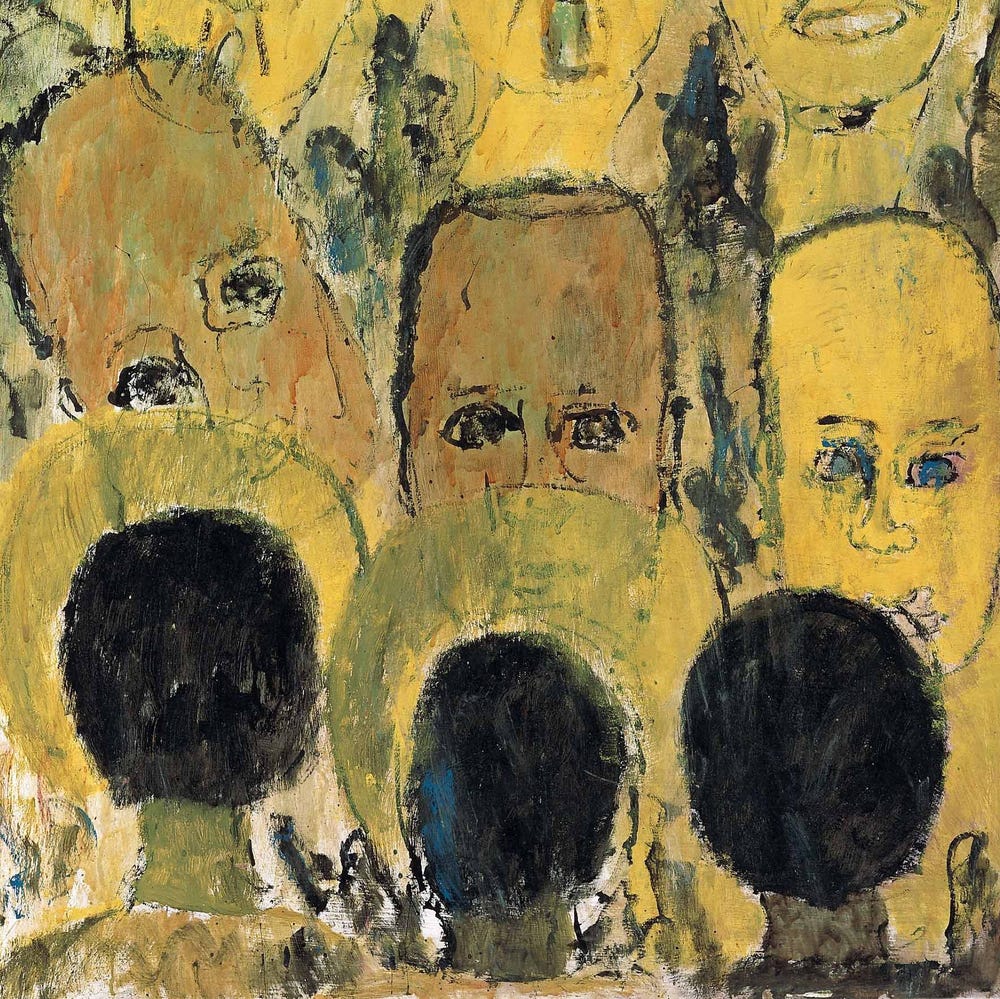

At the height of Patrick Kelly’s fame, his stylistic vocabulary—sewing notions and simple fabrics elevated to haute couture—were enthusiastically embraced by the day’s fashion zeitgeist; buttons, bows, rickrack, and refined jersey body-con shapes became the look. One central facet of the style prism that Kelly honed remained less approachable to the masses, however: the golliwog. Recurring throughout his collections in the form of silk-screened prints and cleverly interpreted button motifs, and even brazenly centered within a crest-style brand logo, was this impish confrontation with America’s (and the world’s) legacy of racist caricature. Its eyes wide, skin coal black, and lips cherry red, Kelly’s golliwog—such an embodiment of the designer’s expression that one forever adorns his Parisian gravestone—is inextricable from the imprint his clothing has left in the Alta Moda annals.

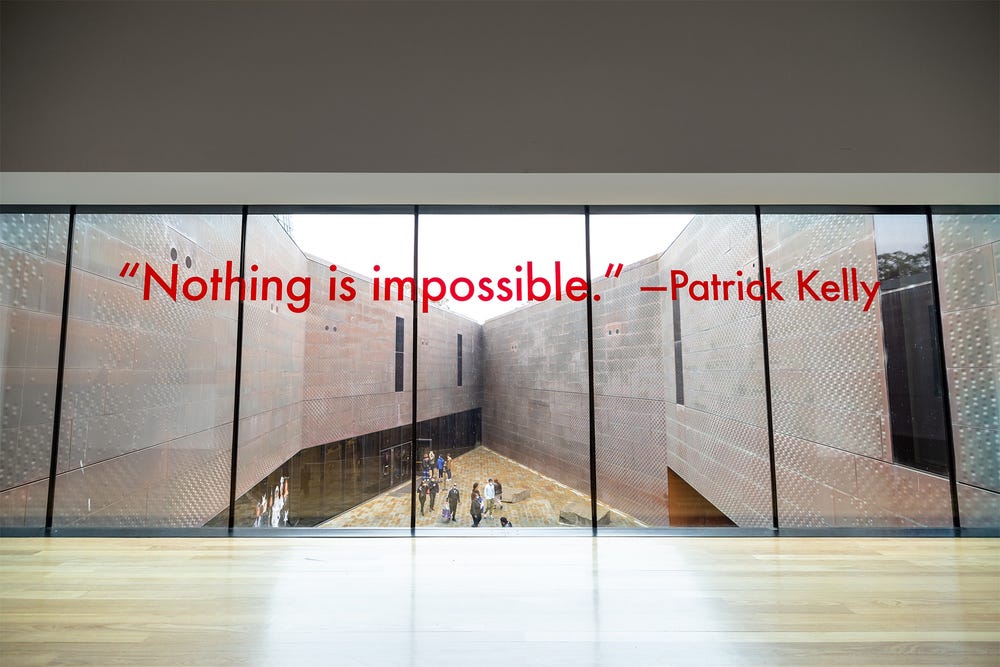

Patrick Kelly Opening Day Donor Reception. Photograph Drew Altizer. Courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

His use of such a divisive ingredient in his otherwise approachable recipe often left the fashion press tiptoeing around what could only be described as the chicest elephant in the room. Kelly dared (as a Black designer achieving international acclaim within white pantheons of cultural arrival) to use his work as a reminder of the ways Blackness had historically functioned throughout the world. Few would call him a “punk” or “political” designer—at least not a “punk” in the subcultural sense or political in the contemporary lane of woke-a-porter. Others would argue that the inherent rebellion tucked into such provocative visual language—rivaling that of Vivienne Westwood or Katharine Hamnett in their respective heydays—could not be described as anything but.

Was it not thoroughly “punk” to sartorially bite the hand of the largely white industry that fed him? He did so by playfully turning on its head an icon of his people’s oppression, demonstrating the conflicted relationship underdogs and outsiders have with cultural acceptance (think working-class tailor Alexander McQueen allegedly sewing the words “I am a c_nt” into the lining of a suit made for Prince Charles).

Industry lore regarding that kind of Trojan horsing is eclipsed by the boldness of Kelly’s hiding his impudence in plain sight. If they wanted in on the Kelly craze, collection-level fashion consumers of all races would have to grapple with the golliwog, an extreme trigger figure. Kelly knew that he had the right to deploy this sort of incendiary catalyst for conversation, even if, at the time, conversations regarding race and representation had yet to find the sophistication in language and democracy of voices they currently pursue. Having been born and bred in the South’s dichotomous culture of Black persecution and perseverance, he had an inalienable right to “go there.”

Installation view of Patrick Kelly: Runway of Love, de Young museum, San Francisco, 2021. Photograph by Gary Sexton. Image courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

Membership does indeed have—if not its privileges—its permissions. These permissions, earned by adversity, grant licenses to those (and only those) who identify as Black. It allows for the sprinkling of N-words throughout hip-hop’s lyrical canon, supports filmmaker Spike Lee’s minstrel allegory Bamboozled in its exploration of pain regularly concealed within Black performance, and permits contemporary artist Kara Walker’s cut-paper silhouettes to excavate the most horrid of antebellum truths buried under the sediment of revisionist history. None of it is easy on the eyes, mind, or soul; all of it toes liminal lines of provocation in the hope of progress.

It begs the question, can one dismantle the master’s house by forgoing his tools and opting for the avatars, iconography, and imagined identities he has assigned to the oppressed? We learn that “reclaiming” treads a slippery slope when embraced by the enfranchised.

To witness this, we must look no further than big fashion’s never-ending cycle of racially insensitive offense and apology: admiration slips into appropriation, which in turn becomes exploitation faster than yet another round of think pieces about these phenomena is penned.

But Kelly’s legacy stands in contrast to these patterns. He was a Black man attempting to almost inoculate himself and others from the disease that is Jim Crow–era racism by microdosing on its semiotic vestiges. In surveying his work, the importance of a Black artist being afforded an opportunity to triumph over trauma from these symbols of oppression becomes apparent. From blackamoor, Zwarte Piet, lawn jockey, and golliwog, to the N-word, sagged jeans, canned ghetto vernacular, and everything in between, we Black artists deserve the first (and perhaps final?) stab at the symbols of our oppression. We’ve earned it and continue to as long as they remain woven into America’s cultural fabric; Aunt Jemima’s “smiling domestic” image was only removed from the company’s syrup bottles in 2020, while Uncle Ben’s grinning deference took until 2021 to be rebranded.

Patrick Kelly quote on de Young museum windows. Photograph Gary Sexton. Courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

Today, a new generation of fashion enthusiasts visits the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco’s retrospective of the designer’s archive, rediscovering not only the exuberance of Kelly’s work but also its gravitas, steeped in complex considerations of what it is to be a Black artist “striver.” It is this writer’s hope that they push the broader fashion industry to atone for the second-class citizenship Kelly’s era of Black designers fought to defy. The most telling measure of our collective commitment to honoring Kelly’s legacy will be opportunities for skilled Black designers (with both a knack for provocation and commercially viable creations) to secure the sort of visibility and industry influence he all too briefly enjoyed. Let us open doors that allow them to walk paths as singular, innovative, and iconic as his, forging new and necessary runways of love in the process.

Text by Kibwe Chase-Marshall (@byanyseamsnecessary), cofounder of The Kelly Initiative (@TheKellyInitiative).

Patrick Kelly: Runway of Love is on view at the de Young museum from October 23, 2021 to April 24, 2022.