James Tissot: Fashion + Faith is the first major reassessment of Tissot’s career in over 20 years. New scholarship on the artist presented in this international retrospective, co-organized with the Musée d’Orsay, and the accompanying monographic publication demonstrate that even Tissot’s most fanciful society paintings reveal rich and complex commentary on topics such as 19th-century society, religion, fashion, and politics. Below is an excerpt from art and fashion historian Justine De Young’s essay in the exhibition’s catalogue, which argues that Tissot’s fascination with ruffles, ribbons, and ruching was about more than just fashion.

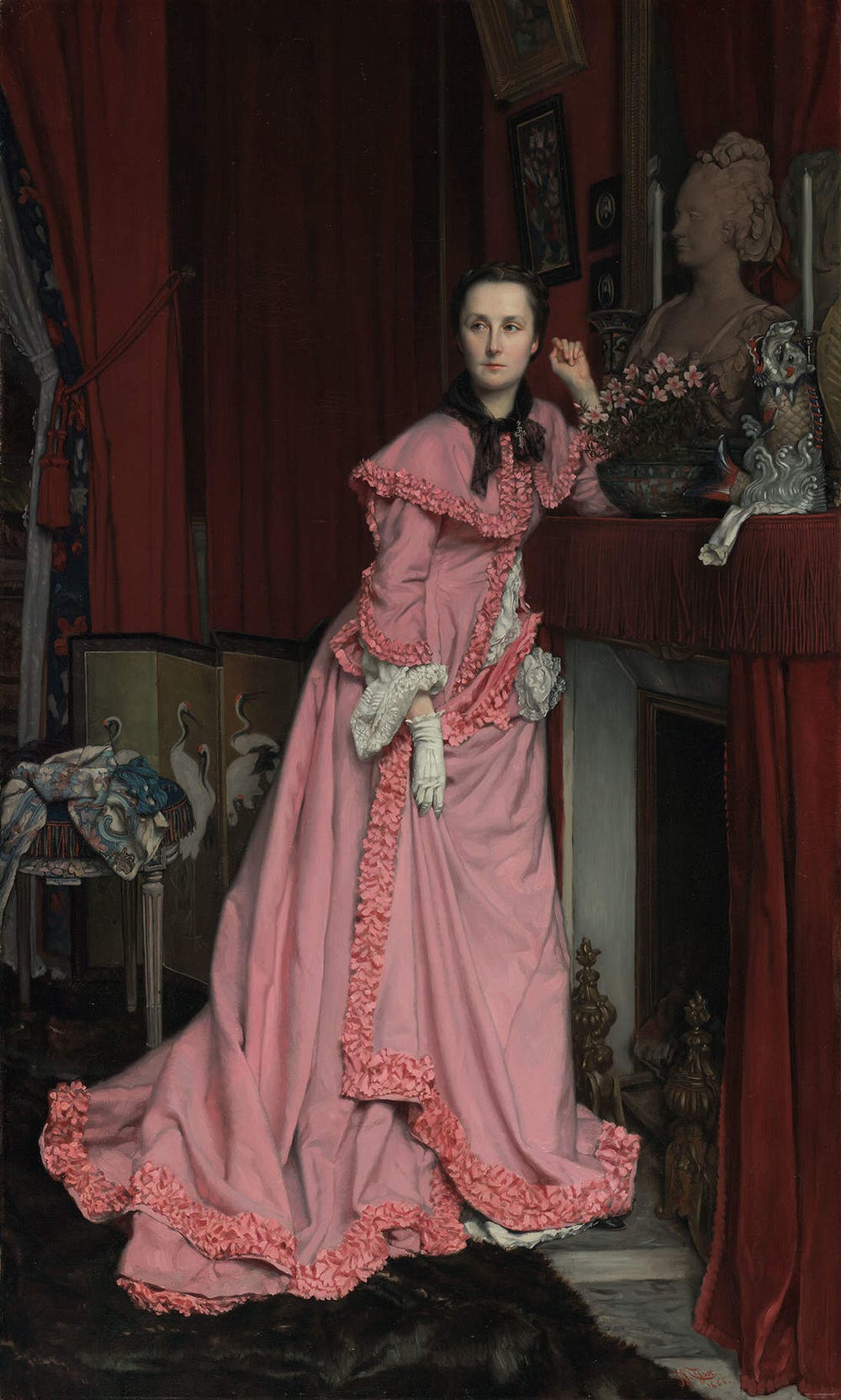

James Tissot, Portrait of the Marquise de Miramon, née, Thérèse Feuillant, 1866. Oil on canvas, 50 1/2 x 30 3/8 in. (128.3 x 77.2 cm). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, 2007.7

The son of a milliner and a marchand de nouveautés, or “seller of the latest dress items,” James Tissot grew up in a household attuned to fashion. His portraits, which he painted throughout most of his career, consistently depicted sitters in fashionable dress, and he became renowned for his highly detailed depictions of clothing. Yet, while the paintings might appear to be superficial renderings of contemporary fashion, Tissot did not merely translate detail into paint. Tissot’s repetition of dresses and accessories — and also models — suggests an artistic fascination with perfecting the familiar rather than the fashionable. Through this repetition, the paintings illustrate how the same dress or even the same woman could be perceived differently, depending on context.

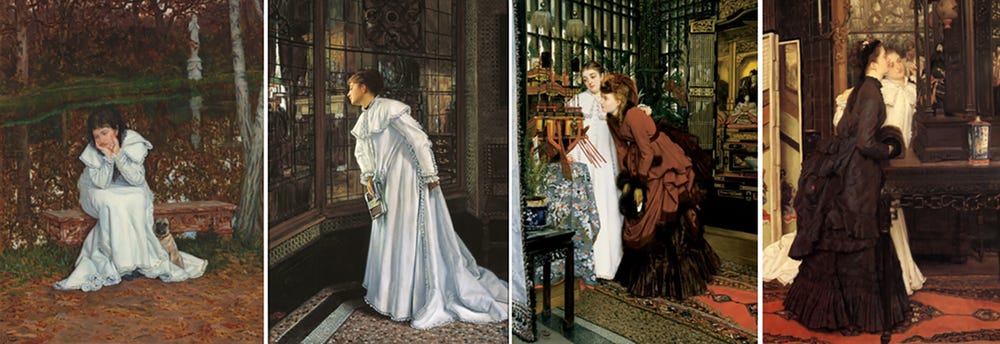

L–R: Melancholy, ca. 1869. Oil on wood panel, 19 1/2 × 14 3/4 in. (49.5 × 37.5 cm). Collection of Ann and Gordon Getty; The Staircase, 1869. Oil on canvas, 22 × 15 in. (55.9 × 38.1 cm). Colección Pérez Simón, Mexico City; Young Women Looking at Japanese Objects, 1869. Oil on canvas, 27 3/4 × 19 3/4 in. (70.5 × 50.2 cm). Cincinnati Art Museum, Gift of Henry M. Goodyear, M.D., 1984.217; Young Women Looking at the Chinese Temple, 1869. Oil on canvas, 22 × 15 1/2 in. (55.9 × 39.4 cm). Private collection

Between 1868 and 1869, for example, he created at least four paintings featuring a white-caped peignoir with fashionable ball fringe, including Melancholy, The Staircase, Young Women Looking at Japanese Objects, and Young Women Looking at the Chinese Temple. The details of both dress and décor in these works were so precise that a critic for L’Artiste declared:

Our industrial and artistic creations may perish our customs and our costumes may fall into oblivion, a painting by Mr. Tissot will be enough for the archaeologists of the future to reconstruct our era.

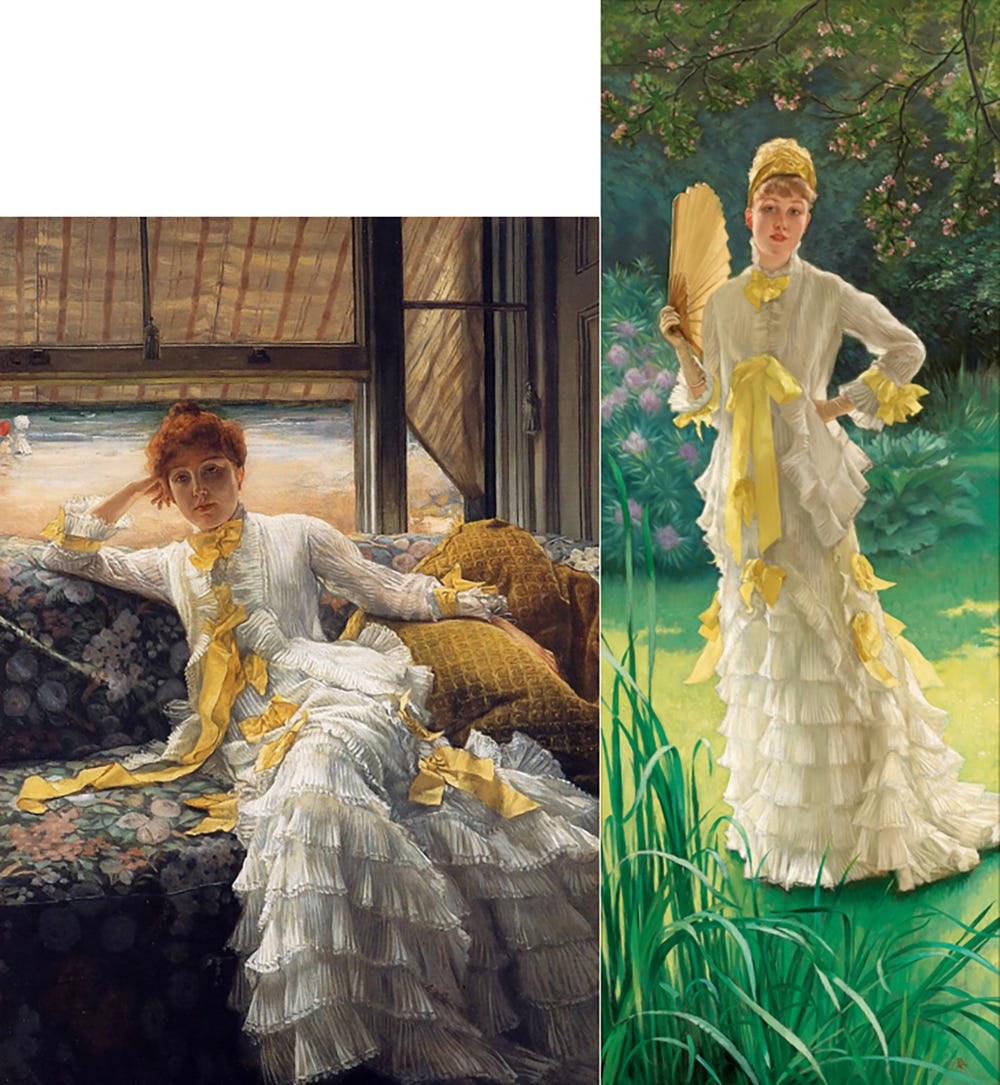

In 1871, after his move to London, Tissot began to repeat himself with greater frequency, developing a repertoire of favorite looks. He seems to have fixated on a set of dresses not for their fashionability but for their formal characteristics — he especially favored stripes, ruffles, and sheer muslin, which were challenging to paint and showcased his talent. This is perhaps most obviously demonstrated by his repetition of a white muslin dress with yellow silk ribbons, seen in Seaside (July: Specimen of a Portrait), Spring (Specimen of a Portrait), and a half-dozen other works.

L–R: Seaside (July: Specimen of a Portrait). Oil on fabric, 87.5 x 61 cm (34 7/16 x 24 in.). Cleveland Museum of Art, Bequest of Noah L. Butkin 1980.288; Spring (Specimen of a Portrait), 1877. Oil on canvas, 55 3/4 × 21 in. (141.5 × 53.3 cm); Collection of Diane B. Wilsey, San Francisco

Tissot’s tendency to repeat dresses is perhaps most dramatically on display in The Ball on Shipboard, which is remarkable for its repetitions both within the piece and for its overlap with other works; every dress represented in the painting appears in at least one other work by Tissot. One example is the gray-and-white-striped dress with a black velvet bodice seen in the left foreground of The Ball on Shipboard. The same dress also appears in Tissot’s London Visitors and Gravesend (also known as Waiting for the Ferry at the Falcon Tavern).

L–R: The Ball on Shipboard (detail), ca. 1874. Oil on canvas, 33 1/8 × 51 in. (84.1 × 129.5 cm). Tate, London, Presented by the Trustees of the Chantrey Bequest, 1937, N04892; London Visitors (detail), 1873–1874. Oil on canvas, 63 × 45 in. (160 × 114.2 cm). Toledo Museum of Art, Ohio, Purchased with funds from the Libbey Endowment, Gift of Edward Drummond Libbey, 1951.409; Gravesend (detail), 1873, also known as Waiting for the Ferry at the Falcon Tavern. Oil on canvas, 26 1/4 × 38 1/4 in. (66.7 × 97 cm). The Speed Art Museum, Louisville, Gift of Mrs. Blakemore Wheeler, 1963.41

The aspect of The Ball on Shipboard that most disturbs and attracts viewers today is what some scholars have referred to as the “decidedly unrealistic” and “strange repetition” of women in identical costumes. Many theories have been proposed to explain the repetition, from attributing it to an ironic commentary on conformity, an imitation of fashion plates, or a kind of stop-motion photographic effect. In fact, it simply was not considered strange in the 19th century for women to dress alike. Sisters often dressed identically, as can be seen in hundreds of surviving carte de visite photos and other artists’ works. While the dresses depicted in Tissot’s paintings were fashionable for the time, their repetition suggests that Tissot enjoyed the technical challenge perhaps even more than the trends themselves.

The Ball on Shipboard (detail), ca. 1874. Oil on canvas, 33 1/8 × 51 in. (84.1 × 129.5 cm). Tate, London, Presented by the Trustees of the Chantrey Bequest, 1937, N04892

Text by Justine De Young, assistant professor of the history of art at the Fashion Institute of Technology, State University of New York. Excerpted from James Tissot, edited by Melissa Buron, director of the art division at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, and published by the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco in association with DelMonico Books • Prestel.

Learn more about James Tissot: Fashion + Faith.

Further Reading

- Élie Roy. “Salon de 1869.” L’Artiste 40 (July 1869): 82.

- Tablet, June 27, 1874, 810, quoted in James Tissot: Victorian Life / Modern Love. Exh. cat. Yale Center for British Art, New Haven; Musée du Québec, Québec City; and Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, 1999–2000. Catalogue by Nancy Rose Marshall and Malcolm Warner. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1999: 15, 87.

- Francoise Tétart-Vittu. “A Summer Dress with Yellow Ribbons.” James Tissot. San Francisco: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 2019: 62-65.

- Michael Wentworth. James Tissot. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1984: 9–10.