Poisons Part II: The Arsenical World of Taxidermy

By Laura L. Camerlengo and Anne Getts

July 20, 2017

Woman’s hat, ca. 1890. Silk faille, velvet, cord, jet beads, and an African starling, 10.2 cm (4 in.) crown height; 21 x 22.9 cm (8 1/4 x 9 in.) overall. Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Gift of Mrs. Caroline Schuman, 53020.6

Readers of Poisons Part I: The Mercurial World of Felt, were introduced to the world of historic feltmakers and their use of mercury. Their repeated exposure to mercury resulted in “mad hatters” disease and eventual death. But mercury was not the only poison historically used in hatmaking, nor is it the only one still present in some of the hats currently on view in Degas, Impressionism, and the Paris Millinery Trade.

When preparing for this exhibition, the Textile Conservation lab first assessed each of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco’s hats using an analytical technique called X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy, or XRF, which allows one to identify the elements present in an object. We were testing the hats for the presence of heavy metals — namely mercury and arsenic — which are known to have been used in hats of this period. It was important to identify which hats, if any, were contaminated, so that proper precautions and handling protocols could be followed in their conservation, preparation, and display.

(L) Woman's hat, ca. 1885 France Plaited straw; silk taffeta ribbon; pheasant wing 52.1 cm (20 1/2 in.) circumference; 30.5 x 28.3 cm (12 x 11 1/8 in.) The Laura Dunlap Leach Collection 1985.40.40 (R) Woman’s hat, ca. 1890. Silk faille, velvet, cord, jet beads, and an African starling, 10.2 cm (4 in.) crown height; 21 x 22.9 cm (8 1/4 x 9 in.) overall. Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Gift of Mrs. Caroline Schuman, 53020.6

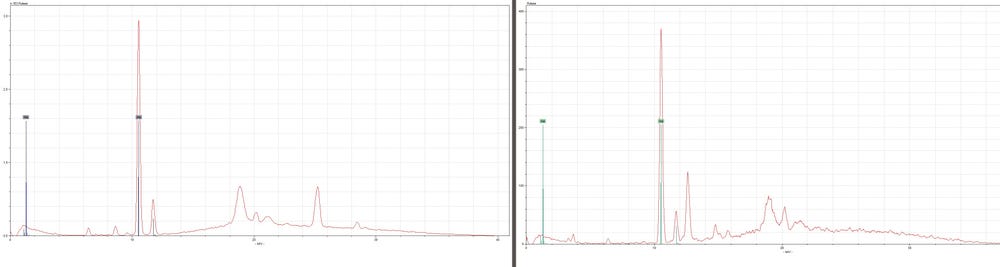

Spectra for pheasant (left) and starling (right).

In addition to the felt hat containing mercury, two hats from the Museums’ collection were found to contain arsenic: a woman’s plaited straw hat with silk taffeta ribbon band from circa 1885 and a woman’s silk hat with jet beading from around 1890. Both by unknown makers, the hats are each distinguished by prominent decorations of taxidermic fowl. The woman’s straw hat features a wing of brilliantly marbled and speckled feathers at its front, while the silk hat has an entire African starling, with wings outstretched, perched above its front brim.

Like mercury’s role in felt-making, arsenic was a key ingredient in historic taxidermy processes. The use of arsenic was popularized by the French ornithologist, taxidermist, and curator for Muséum national d'histoire naturelle, Louis Dufresne (1752 – 1832). Dufresne used arsenical soap to preserve birds for the Muséum’s collection, which became one of the finest collections of its kind in the world. The technique then migrated to England in the early nineteenth century, and reached its heyday in the Victorian age.

A taxidermic bird specimen would be prepared by skinning the bird, hollowing out its body cavity, and leaving the skull, wing bones and legs intact. The interior would then be treated with an arsenical compound — usually a powder or soap — to preserve the skin. The body cavity was filled with stuffing. Wires would be inserted into the specimen to provide support, and could also be used to attach the specimen to its mount, or in some cases, to a hat.

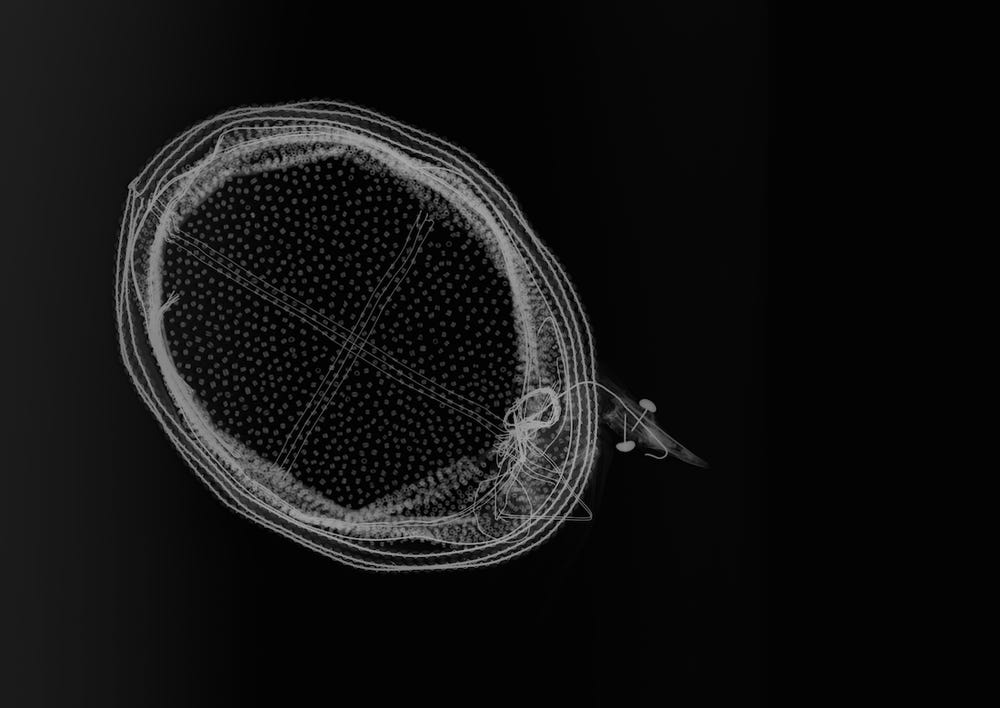

X-ray of the woman’s hat with the African starling

In addition to XRF testing, the woman’s hat with the African starling was also imaged with digital x-radiography, which allowed the interior of the bird specimen to be seen. Interior wires threading through the skull and body are clearly visible, as are the glass eyes, which are held in place with wires.

While an entire pheasant is not perched on the brim of the woman’s plaited straw hat, the wing that adorns this hat was also treated with arsenic. Because the feathers remain embedded in the skin of the wing, the specimen required preservation to prevent decay. This is an interesting distinction to make: none of the hats that are decorated with detached feathers tested positive for arsenic, as singular feathers harvested from a bird do not require the same level of preservation that a specimen containing skin does.

The harvesting of both birds’ bodies and their feathers for women’s fashion is a large and interesting topic – one that leads to the creation of the Audubon Society. Learn more and see the hats in person at Degas, Impressionism and the Paris Millinery Trade, open through September 24.

Further reading

Dickinson, J.A. “Taxidermy.” In The Conservation of Leather and Related Materials, edited by M. Kite and R. Thompson, 130-140. London: Butterworth-Heinemann, 2006.

Farber, Paul Lawrence. "The Development of Taxidermy and the History of Ornithology." Isis 68, no. 4 (December 1977): 550-566.

Péquignot, Amandine, Fernando Marte, and David W. von Endt. “Arsenic in Taxidermy Collections: History, Detection, and Management.” Collection Forum 2006: 1.

Rookmaaker, L.C., P.A. Morris, I.E. Glenn, and P.J. Mundy. “The ornithological cabinet of Jean-Baptiste Becoeur and the secret of the arsenical soap.” Archives of Natural History 33, no. 1 (2006): 146-158.

Text by Laura L. Camerlengo, assistant curator of Costume and Textiles, and Anne Getts, Mellon assistant textiles conservator.