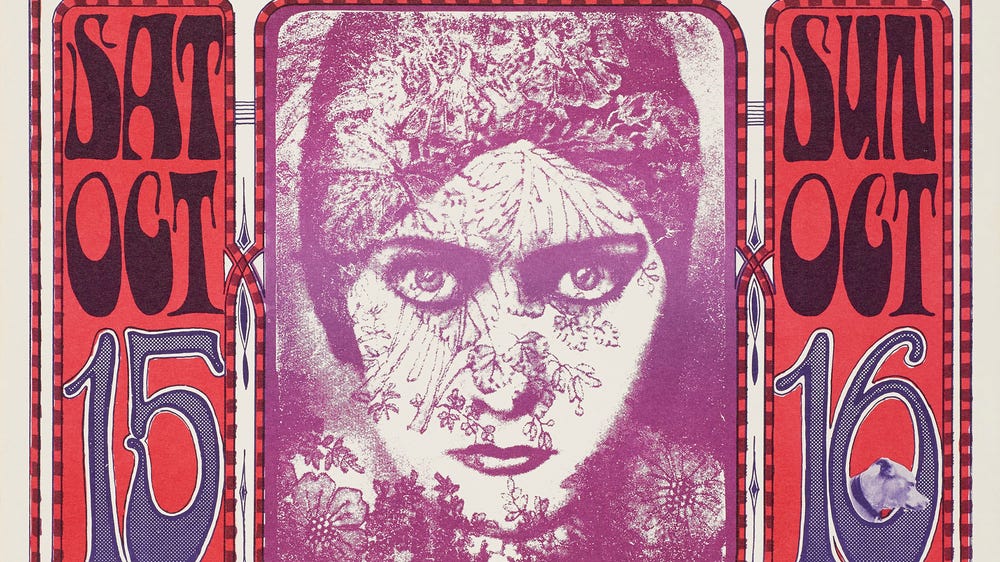

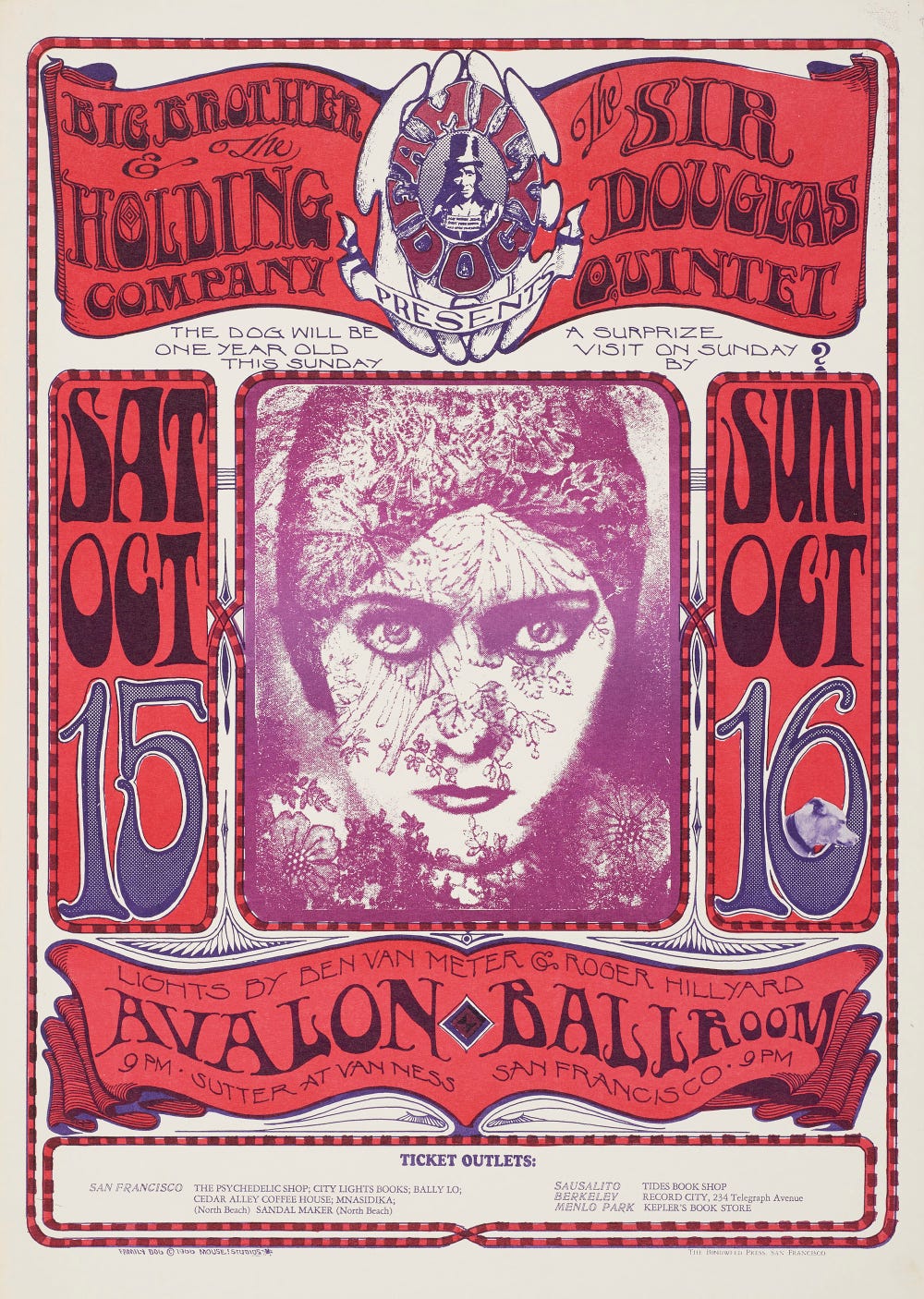

Stanley Mouse and Alton Kelley, Gloria Swanson, Big Brother and the Holding Company, Sir Douglas Quintet, October 15 & 16, Avalon Ballroom, 1966. Color offset lithograph poster. Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Gift of Mr. Julian Silva, 1997.64.12. Artwork by Stanley Mouse and Alton Kelley. © 1966, 1984, 1994 Rhino Entertainment Company. Used with permission. All rights reserved. familydog.com

On June 30, the recently launched book club of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco Page Views met to discuss The Girls by Emma Cline and its parallels to The Summer of Love Experience, moderated by professor Rob Sean Wilson (UC Santa Cruz). Cline, a native of Northern California, dropped by to visit the exhibition and graciously agreed to answer some of our Page Views participants’ questions.

You managed to really capture a lot of small details and references of the time with the familiarity of someone who lived during that period. What were your favorite methods of research?

— Elizabeth M.

Emma Cline: It was a tricky balance — how to create a vivid atmosphere while not relying too heavily on the clichés and cultural cues of 1969. I tried to focus on how this particular teenage girl would experience her own particular life, and that helped keep the book grounded in one character’s life. I definitely did a lot of fun research — from reading my mother’s teenage diary to reading biographies and watching documentaries. I lost a day or two listening to archived radio shows from 1969 — it was amazing to me that it’s possible to listen to the radio that my character might have listened to on that exact day in the summer of 1969.

Ruth-Marion Baruch, All the Symbols of the Haight, 1967. Gelatin silver print. Lumière Gallery, Atlanta, and Robert A. Yellowlees

“I waited to be told what was good about me. [...] All that time I had spent readying myself, the articles that taught me life was really just a waiting room until someone noticed you — the boys had spent that time becoming themselves.”

Evie Boyd struggled to fully form a unique, whole, authentic self during her formative years while the boys around her were encouraged to. Do you think this experience is changing for youth as we seek to equalize gender? What more can we do to support that identity formation in young women? Thanks for being such an inspiring young female artist

— Amy H.

EC: This was a lot of what I wanted to circle around in the book: why is this young woman, Evie, so vulnerable to outside narratives and influences? How much has changed for adolescent girls, or is there something universal in wanting so badly to be seen and known? This book definitely tries to account for the viewpoint of a young woman, subject to the manipulations and abuses of men around her, but I think it also talks about a group of women who’ve internalized the male gaze and inflict it on each other, while also struggling to connect with each other despite the framework of the world they’ve been given.

There was a lot about the sixties era that spoke specifically to the concerns of the novel — female relationships, the lack of sexual agency. At the same time, having a modern framing story was a way to think about what hasn’t changed since 1969, and what about this story might be universal. As opposed to Evie, Sasha is a character who has benefitted from growing up in contemporary America, with its supposed feminist progress. Writing the scenes between them in the novel was a way for me to think about what hasn’t changed, or consider what might connect this older woman and this young girl, despite the decades between them. I didn’t come to any hard or fast conclusions, which is one of the nicest things about being a novelist — I get to ask questions, create juxtapositions, without having to tie things up in any definitive way.

The Girls offers an anti-romantic and dystopian narrative of Californian communalism and the revolutionary energies of the 1960s. Are there utopian energies or values in our present that you think survived the time?

— Professor Rob Sean Wilson

EC: I’m not really sure! I wonder if the Internet has made certain kinds of collective energies impossible, because it gives people the ability to operate in their own world. It has a fracturing effect on certain movements, at least in my experience.

Stanley Mouse and Alton Kelley, Gloria Swanson, Big Brother and the Holding Company, Sir Douglas Quintet, October 15 & 16, Avalon Ballroom, 1966. Color offset lithograph poster. Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Gift of Mr. Julian Silva, 1997.64.12. Artwork by Stanley Mouse and Alton Kelley. © 1966, 1984, 1994 Rhino Entertainment Company. Used with permission. All rights reserved. familydog.com

We loved the duality of sunshine and noir underbelly in your Northern California setting. Do you plan on exploring the golden state further in your future works?

— Danielle H.

EC: I love writing about California — it’s a landscape of great beauty, but is also a place that isn’t fully safe — there are earthquakes and Valley Fever and droughts, this sense that all that loveliness comes at a very real cost. That dichotomy — great beauty and great darkness — is something I wanted to circle around in this book. California is also a place built on these fantasies of becoming someone else or living a heightened life — Manifest Destiny, the Gold Rush — and I wanted to write about those desires taken to their extreme, the end point of a certain kind of idealistic narrative. I’m writing a few stories set on the East Coast, but I’ll always love writing about Northern California in particular. It’s endlessly fascinating to me.

We were so pleased you had the opportunity to visit The Summer of Love Experience at the de Young. Were there any items on view or rooms that particularly sparked a feeling of connecting to the world you created for The Girls?

— Page Views

EC: I loved visiting the exhibit. Standouts were seeing the notes from the bulletin board, which gave such a good snapshot of a moment in time, as well as the ephemera for things I had only read about — like The Invisible Circus. And of course the music posters, which were incredible and vivid. It makes a huge difference seeing these objects in person.