In the past decade, modest fashion—highly stylish dress with varying degrees of body cover—has become one of the most pervasive international fashion stories, with articles on the subject published almost daily in the press in 2016 and 2017. Reporters attribute this emerging market to the spending power of the Muslim female consumer, generally locating the phenomenon in the Gulf States. Reflecting this focus, the State of the Global Islamic Economy Report from 2016–2017, produced by global strategy research firm Thomson Reuters and DinarStandard, estimated modest fashion purchases by Muslim women at $44 billion USD per year, approximately eighteen percent of the total estimated $243 billion spent by all Muslim consumers on all clothing; global spending on apparel is expected to reach $368 billion by 2021—up fifty-one percent from 2015.

As the Western world awakens to the size of Muslim spending power, major retailers have responded accordingly. Brands such as American Eagle, Carolina Herrera, DKNY, Dolce & Gabbana, H&M, Mango, Nike, Tommy Hilfiger, and Uniqlo have all begun to offer collections that adhere to modest Muslim dress codes, while the work of emerging and established Muslim designers within the modest fashion sector has begun to garner attention on an international scale.

In the past decade, modest fashion weeks have taken place in cities around the world, including Dubai, Istanbul, Jakarta, Kuala Lumpur, and London, creating a platform for Muslim designers from both Muslim-majority and Muslim-minority countries. Such designers are also being included in mainstream Western fashion schedules in growing numbers; in 2017 Muslim modest wear featured sequentially in New York Fashion Week, Torino Fashion Week, and Paris Fashion Week as well as Fashion Forward Dubai, a showcase for Middle Eastern designers of all genres, now celebrating its tenth anniversary.

Aidijuma’s Spring/ Summer hijab collection featured at Modanisa London Modest Fashion Week, April 15, 2017. Photo by Rooful Ali/ Rooful.com

This burst of activity has drawn the critical eyes of fashion and lifestyle reporters, who have suggested several hypotheses as to why the fashion world is experiencing a modest moment. It’s imperative to note, however, that fashionable modest dress is not new, despite the commercial sector’s and mainstream media’s relatively recent awareness of and interest in it. Academic and specialist commentators have been tracking such practices for some time, and costume sociologists have been observing this cultural shift since the turn of the twenty-first century. As Alia Khan, founder and chairwoman of the Islamic Fashion and Design Council (IFDC), points out: “This kind of dressing has gone on since the beginning of time and it’s going to go on to the end of time.”

Meet some of the many designers, entrepreneurs, and analysts involved in the contemporary modest Muslim fashion sector and hear from them about the industry’s multifaceted nature and audience, its sartorial and political significance, and the reasons that modest fashion is much more than a trend.

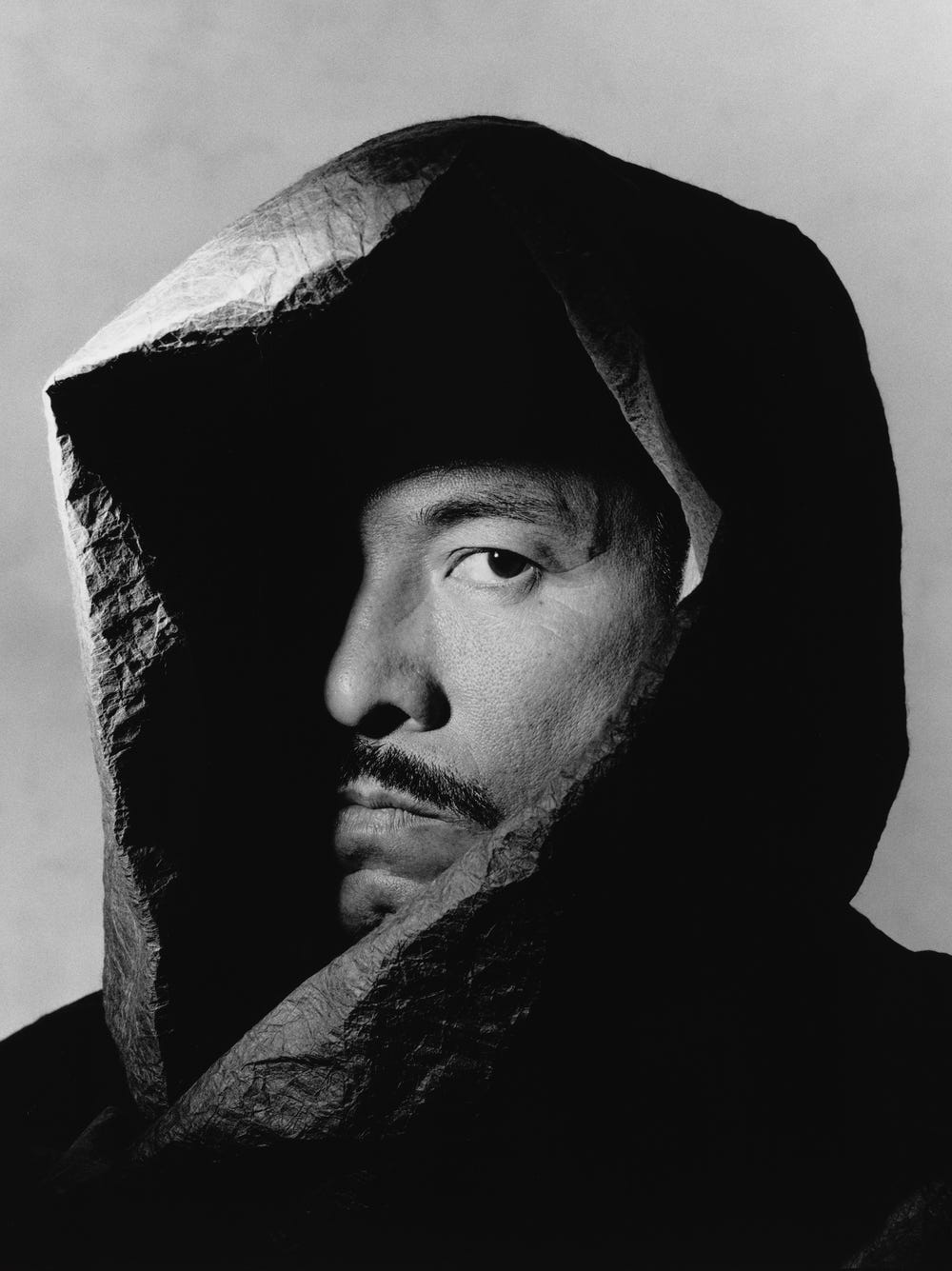

Kerim Türe, CEO, Modanisa

The growing interest in modest fashion is often attributed to the Muslim millennial woman, but in fact its aesthetic speaks to a far broader demographic, one that encompasses women of different faiths and sometimes does not concern religion at all. Kerim Türe, CEO of Modanisa, an Istanbul-based e-commerce site offering modest affordable luxury, cautions against privileging a single definition of modest fashion:

“The mistake of mainstream fashion is seeing modest fashion as a uniform or ethnic clothing. Muslim fashion and Muslim clothing is not a uniform . . . it’s more than that. What we see here are great women, open-minded, willful, strong women showing the world that they care about fashion and they have a great sense of style.”

—Reina LewisThis movement is really driven by an empowered new demographic who are expressing their presence in the modern world, and attempting to assert their place in it.

Reina Lewis, professor of cultural studies at London College of Fashion, author of Muslim Fashion: Contemporary Style Cultures, and consulting curator for Contemporary Muslim Fashions

Says professor, author, and curator Reina Lewis: “Modest fashion and Muslim fashion are no longer on the periphery of the industry, and an industry that stopped being able to afford to be elitist and exclusive long ago. This movement is really driven by an empowered new demographic who are expressing their presence in the modern world, and attempting to assert their place in it.”

From The Modist launch campaign, 2017. Courtesy of The Modist and Daniel Nadel

Ghizlan Guenez, founder, The Modist

The luxury fashion e-commerce site The Modist, which boasts a woman at its helm, has perhaps best captured the movement’s zeitgeist. The site, which identifies as being by women for women, symbolically launched on International Women’s Day in 2017. Founded by Ghizlan Guenez, a Muslim former private equity director who splits her time between London and the United Arab Emirates, the project grew out of her frustration at the lack of availability of stylish, modest clothing, even in Dubai. The site launched with seventy-five designers, and in less than a year had more than one hundred twenty. In an interview with Refinery29, Guenez discusses how modest Muslim fashion transcends traditional garments:

“There is a conversation and a momentum that is building around expressing the different nuances to modest dressing. . . . [While] one facet of dressing modestly is embodied in the hijab and abaya, it is not the only facet. Modesty is such a wide spectrum, and it is important to appreciate the diversity of the modest dresser and not peg it into one stereotype.”

With an eye for high fashion, The Modist flourishes with a uniquely broad international perspective on contemporary fashion, ranging from the clean minimalism of BOUGUESSA (United Arab Emirates) and Sofie D’Hoore (Belgium), to the bold prints of Mary Katrantzou (b. Greece, based in UK), folkloric embroideries by Yuliya Magdych (Ukraine), and accessories by Lanvin (France), plus signature oversized silhouettes from Elizabeth and James (United States).

Although Guenez created The Modist with the needs of the Muslim woman in mind, it became clear after the site’s launch that there was equal demand from non-Muslim women for high-end modest styles. The company ships to more than one hundred countries worldwide, with the Middle East, the United States, and Europe as its target markets. As of January 2018, the United Arab Emirates remains the top destination, with the second being the United States, where only ten percent of the site’s customer base is Muslim.

Mashael Al Rajhi, designer

Says Saudi fashion designer Mashael Al Rajhi, whose cutting-edge deconstructed looks continue to draw the attention of the fashion press: “Right now, if we’re looking for a more globalized view on fashion, you have to have representation from all its hemispheres. This is how we move forward, design should not be confined or boxed into restrictive mindsets, East and West needs to mesh now to create beautiful things. Fashion should be socially conscious, we have the ability to influence mindsets, and it is a form of expression and freedom. It allows us to form our identity and give people the chance to achieve their potential.”

From March 2017 Vogue Arabia: Dress and belt, Rosie Assoulin; overcoat, Rosie Assoulin for Net-a-Porter.com; vest, Frame; earrings, Céline; bag, Gabriela Hearst. Vogue Arabia, March 2017, p. 74; Courtesy of Vogue Arabia and Marcin Tyszka, photographer

Deena Aljuhani Abdulaziz, editor, Vogue Arabia

The pages of Vogue Arabia display a decidedly global approach. Launched in March 2017, the regional title is distributed in several Middle Eastern countries, including Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Qatar, Kuwait, Oman, the United Arab Emirates, Jordan, and Lebanon—all wealthy regions characterized by sophisticated high-end fashion consumers. The pages intersperse profiles of empowered Middle Eastern women with luxurious fashion spreads that blend both modest and mainstream designs with such aplomb that an unknowing eye would notice no clear distinctions. In an interview with the New York Times, founding editor Deena Aljuhani Abdulaziz explains that “Vogue Arabia is not just about appealing to our own region, but about providing a cross-cultural bridge, a beautiful source of inspiration you would want to pick up even if you were from another area.”

For example, the March 2017 issue features a long dress and shirt by the Brooklyn-based designer Rosie Assoulin, who is of Sephardic Jewish heritage and whose work has garnered the attention of both Orthodox Jewish and Muslim modest dressers, underscoring the cross-cultural commonality among faith-based dress codes. The facing page features an oversized shirt by Joseph—the London-based fashion brand founded by Moroccan entrepreneur Joseph Ettedgui and his family—paired with Stella McCartney parachute pants.

—Mariam Bin MahfouzAn abaya is a superhero’s cape and women are the modern-day superheroes.

Mariam Bin Mahfouz, founder, Sotra; founder, Haal Inc.

Saudi fashion designer Mariam Bin Mahfouz has founded two labels—Sotra, an affordable luxury label, and Haal Inc., which focuses exclusively on the abaya, a traditional loose-fitting, robe-like garment. The universality of modest dress does not surprise her. “I feel that modesty is a global theme throughout all religions, throughout time. It’s human nature to want to conceal and to cover up, and to drape something on the body. To what extent is very much dependent on the environment, the culture.”

While the recent trend in abaya design in Saudi Arabia leans toward surface embellishment and color, Bin Mahfouz’s Jeddah showroom features a refined selection of abaya in a limited palette of black, white, and cream. The designer is most interested in the shape and tailoring of the garment and the drape and feel of the cloth. “There is luxury in wearing the abaya,” she says. “I see it as an empowering garment, more than being restrictive. It feels very grand, very sophisticated.” As she told Vogue Arabia, “An abaya is a superhero’s cape and women are the modern-day superheroes.”

Alia Khan, founder, Islamic Fashion and Design Council (IFDC)

Pakistani American Alia Khan founded the Islamic Fashion and Design Council (IFDC) in 2012 as a platform to promote Islamic fashion and design within the global marketplace, and she continues to serve as the council’s chairwoman. Headquartered in Dubai, the council offers services such as designer portfolio reviews and a retail consultation management program and produces an online publication, Cover Magazine, which has an interactive feature called Pret-A-Cover Fashion Week. Khan speaks to the long history of modest fashion:

“It is not a new market at all. [For the women who choose to dress this way] it is not a fad. It is not in this season and out the next. They are going to do it for a lifetime. If you can win them over, you have a loyal audience, a loyal customer.”

Since its inception the IFDC has participated in several runway shows in Muslim-majority countries, including Jakarta Fashion Week, Istanbul Modest Fashion Week, and the Asia Islamic Fashion Week, in Kuala Lumpur. In June 2017 it partnered with Torino Fashion Week, which, for three days, showcased thirty designers from around the world who were creating Muslim-friendly collections. This was the council’s first collaboration with a mainstream fashion week, and two months later it showed during Paris Fashion Week. “Fashion is a soft language,” Khan wrote in an email correspondence with the author. It has the ability to “explain who we are and can break down sociopolitical prejudices in a better way.”

It was this outfit, by Al Nisa Designs, that reporter Hafsa Lodi was referring to in the headline “How These Hijab-Wearing Pink Ladies Stole the Show at Torino Fashion Week,” for her article in The National. Al Nisa Designs, Torino Fashion Week, Turin, Italy, June 2017. Courtesy of Al Nisa Designs

Carmen W. Muhammad, designer, Al Nisa Designs

Los Angeles–based Muslim designer Carmen W. Muhammad was also at Torino Fashion Week. There she received one of the top three designer awards from Ala Hamdan as well as the Louis Vuitton honorary brand award. A member of the Nation of Islam, Muhammad founded her clothing line Al Nisa Designs in the mid-1980s after several years of working in the business and entertainment industries.

Out of one hundred twenty-five participants, Muhammad was one of five invited from the United States and was the only black modest designer to present. In her review of Torino Fashion Week, Hafsa Lodi, lifestyle reporter for The National, referred to Al Nisa’s designs in her headline—“How These Hijab-Wearing Pink Ladies Stole the Show at Torino Fashion Week”—and described her “corporate-style pantsuits with flared trousers, knee-length, collared, button-down tunics and matching veils, all in the on-trend hue of millennial pink” as a fitting option for a professional woman seeking an ultra-modest power suit.

For Muhammad, the opportunity to show at Torino Fashion Week was about much more than fashion; for her it was about the women of the Nation of Islam whom, she said, she was both proud and humbled to represent in Italy. In a phone interview a few months after the event, Muhammad was full of optimism: “There are so many stereotypes about Islam and Muslim women as being oppressed. By exhibiting at a mainstream fashion event, the world saw a free woman, who freely expressed herself, who freely dressed herself, who freely created her designs.” She continued:

I have the belief that there are some industries that exist—sports, entertainment, music, and fashion—that are so powerful that they become ambassadors for peace. When you are operating within those industries, you have the potential to bring people together regardless of their race, social background, or economic status. This is my mission, to use my creative talents in fashion to promote peace and goodwill in the world.

Dian Pelangi (b. 1991, Indonesia), “Ereditá Srivijaya” ensemble (top, cape, headscarf, and skirt), Torino Fashion Week 2017; Silk satin, metallic braid, supplementary-weft patterning with metallic thread (Palembang songket), Thai silk. © Dian Pelangi

Dian Pelangi, designer

With 4.8 million Instagram followers, Indonesian designer and social media influencer Dian Pelangi is credited with pushing the traditional boundaries of Muslim fashion forward with her vibrant, colorful fusion of Eastern and Western cultures, which draws equally upon the rich heritage of Indonesian fabrics and techniques such as batik, tie-dye, and songket (a traditional Indonesian textile distinguished by gold-thread supplementary-weft patterning) and Western silhouettes. Like many Muslim designers, she received formal training from a Western fashion academy—she graduated from École Supérieure des Arts et Techniques de la Mode in Paris in 2008.

In 2017 Pelangi showcased her designs during the New York Fashion Week Spring/Summer 2018 collections, along with five other Indonesian designers, in a presentation titled “Indonesian Diversity,” sponsored by the Manhattan-based boutique Indonesia Fashion Gallery. Pelangi’s collection, Alurrealist, was inspired by the book Humans of New York, by Brandon Stanton. In a September 8, 2017, Instagram post, she described the collection’s narrative as centering on the busy, vibrant, and diverse metropolis. Her decision to create a collection celebrating the show’s host city is noteworthy. Rather than presenting an exoticized Indonesian export, she used traditional Indonesian textile techniques to pay homage to New York, a city whose crowded urban environment rivals her home base of Jakarta. In doing so she established and acknowledged parallels and commonalities between the two urban centers. As with other modest Muslim fashion designers, Pelangi wanted it known that “we’re not oppressed and we just want to show the world that we still can be beautiful and stylish with our hijab on.”

Vivi Zubedi, designer

Fellow Indonesian Vivi Zubedi made her decision to present her work at New York Fashion Week expressly in reaction to the executive order that President Donald Trump attempted to pass on January 27, 2017, that would have restricted immigration from seven Muslim-majority countries—Iraq, Syria, Iran, Sudan, Libya, Somalia, and Yemen. In a bold statement to The Guardian, Zubedi remarked: “Mr. President, I love your country and also I love your people, and we will not do anything to you or your people. We are all the same, it’s about humanity.”

—Jess Cartner-MorleyClothes can express what society values in women—and what it fears.

Beyond Fashion

It’s clear that the implications of modest dressing reach far beyond both fashion and Muslim dress codes. Guenez, of The Modist, defines the current universal appeal of modest fashion as a “macrotrend”—a trend that goes beyond fashion. As Jess Cartner-Morley writes in her September 2017 Guardian article, “The Great Cover Up: Why We’re All Dressing Modestly Now”: “Clothes can express what society values in women—and what it fears.” Susan Michelman, in her 2003 article “Reveal or Conceal? American Religious Discourse with Fashion,” connects modest dressing with the conservative bent of the 2000s. Writing in the years of the George W. Bush presidency (2001–2009), she observes that:

"America is in a politically conservative period, including an increased interest in more fundamental religious beliefs, which are linked to modesty. In the current social environment, the interest in modesty is much more than a shift in fashion from immodest to modest or a predictable change in the continuous cycle of fashion that discards something old for something new and trendy."

Within the context of Michelman’s thesis, we can then understand the end of the naked look that typified the 1990s through recent years as a reflection of a new age of feminism in which women are empowering themselves by choosing styles that prioritize the individual and their needs over entrenched notions of female sexuality and desirability. The move away from body-conscious fashions, which some women associate with ideas of liberation and empowerment, provides a wider context for the new market interest in modest coverage. Guenez reflects upon this shift:

"I believe there was a point in time when women associated empowerment with baring all. If you’re strong, you’re out there with 'it’s my body' and 'I should be able to show it.' And we’ve gone through that phase. I think that maybe we’re becoming a little smarter and understanding empowerment for what it truly is, which is whatever makes you happy and comfortable—and whatever your choice is, exercising it is empowerment, whether it’s covering or baring."

In the political landscape that has now taken hold in the United States—with issues of gender equality and sexual harassment at the forefront—modest fashion is also seen by some advocates as a tool to fight gender inequality. From oversized power suits, floor-length coats, and long-sleeved flowing gowns to gender-neutral clothing and swaddling layers, these fashions are being showcased in magazines and on runways worldwide in both the mainstream and modest fashion realms. It is intriguing to note that the sartorial inclinations of women in pantsuits and maxi-dresses are akin to clothing choices women made in the late 1960s, a time when issues of female equality were also at the forefront, and similarly such clothing choices were a site of social discourse.

It’s worth noting that it is the identity of the young, professional Muslim woman that has captured the zeitgeist of modest dressing. As they have gained more prominence, these women have demanded and created both a platform that suits their own faith-based needs and a market for stylish modest fashion that serves the needs of a diverse spectrum of women. Hence, their impact goes beyond fashion trends. Anthropologists and sociologists have been following the trend for at least a decade longer than the fashion press, further suggesting this is a cultural and societal shift that will not go away with the next season—certainly, not for the Muslim consumer.

Jill D'Alessandro is curator in charge of costume and textile arts in The Caroline and H. McCoy Jones Department of Textile Arts at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. This text was adapted from her essay "Global Style: Muslim Modest Fashion Today," published in Contemporary Muslim Fashions (Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco / Delmonico Books ● Prestel, 2018).