Episode 2: So Many Details!

Raquel: What do you think of when you hear the word density? The word itself means compactness of pieces coming together. But what about in terms of art?

Noelle: When I think of density and art, I think of busy paintings that have many pieces that are a part of a bigger puzzle.

Zune: Density to me feels like a crowded room with no space to breathe. The busy-ness in our chosen artwork actually serves many purposes. They can represent ideas that the artists want to put forward. It can also reveal deeper meanings.

Raquel: Yes, the detail is what makes the artwork so unique. All the parts work together to create an interesting and rich work of art.

Noelle: Hi, I'm Noelle and I'm 13.

Zune: And I'm Zune. I'm 17.

Raquel: And I'm Raquel. I'm 19. And we're museum ambassadors at the Fine Arts Museums here in San Francisco. In this episode, we are discussing density in art and how it can reveal the artwork's meaning.

Noelle: I personally love seeing density and detail in artwork. It makes me want to know more, to look closer and gives me a chance to connect with it on a deeper level.

Zune: Totally. But other people might feel overwhelmed with all the details.

Raquel: Throughout this podcast, think about what density means to you. How does it make you look at an artwork?

Noelle: In case you have no idea what a sarcophagus is, don't worry. I didn't either. Here's some facts to bring you up to speed. Roman sarcophagi are essentially coffins that were mostly used in the second century, which was almost 2000 years ago. Sarcophagi were made of stone, lead, wood and for those with wealth or those who could afford it, marble.

We're going to discuss how each detail on the sarcophagus relates to the deceased and how it reflects different aspects of their life. It's actually very surprising how much you can learn about a person just by studying their sarcophagus.

The reason I was drawn to this piece initially when thinking of the theme density is because of all the things going on in it. There's just so many details to soak in. Something that you may be wondering is what kind of person would have the sarcophagus. I asked Louise Chu and Renee Dreyfus, ancient art curators, how much skill had to be put into making this.

Renee Dreyfus: This is a very intricate and very beautiful sarcophagus, a very impressive one, meant that the artist would have been a very fine sculptor working in marble. What is amazing is that you get this sense of three dimensionality on a work like this sarcophagus where figures stand out in the front and others are in the back. As I say, some of the arms, some of the actual figures are standing out away from the surface.

Noelle: My next wonder was who could afford such a beautiful and luxurious thing?

Renee Dreyfus: This sarcophagus, this burial box, was bought for, would have had to have had a lot of money. The person for whom it was bought is the woman in that circle, in the middle of the sarcophagus. She is a noble woman coming from one of the fine Roman families that had the resources to be able to purchase a box like this. Also, and it's so extraordinary to think about, she's holding onto her cloak with her right hand. And in her left hand, the woman holds a scroll, which is what they used for writing on. So it's showing off in some ways that not only was this woman wealthy, but she was literate.

Noelle: So what I was wondering at this point was, what role did a sarcophagus have in their culture if people were willing to pay so much to have such an ornate one?

Renee Dreyfus: Well, on the one hand, these very intricate and very beautiful sarcophagi would be used to impress anyone. The actual sarcophagi would be placed in a niche and in a place where others could see it. So much of Roman culture is kind of showing off what you can afford.

Noelle: The carvings and designs are of the farming year and things related to Dionysus who’s the God of wine, vegetation, and resurrection. They were very popular themes at the time. Bare figures are standing all around holding fruits according to the season. Little, almost childlike wingless gods, similar to Cupid are playing below with animals which is a panther, which is linked to Dionysus. The inclusion of the seasons and Greek symbols show beliefs and the constant progress of time in the nature of life, death, and the wish for rebirth. Even though this isn't exactly a narrative, you can tell that the owner was educated and held beliefs that dated back to ancient Greece. Speaking of which, how did these carvings represent their beliefs?

Renee Dreyfus: The sarcophagus, all of these images, the ones in the front, the ones in the back, all of them have something to do with fertility. The sarcophagus also is a very strong way of depicting what is hoped for in the next world or in the life to come, in the hereafter. Just like certain times of the year, the plants grow forth and in other times of the year, they die out. But don't worry because they will come back again fresh and renewed the next time around. It was hoped that the way the fertility of the land and the fragility of the crops happens over a period of time. So likewise, this woman would experience a rebirth.

Noelle: What kind of customs would go along with it to honor the deceased?

Louis Chu: That stratum of a Roman society, as Renee was saying, there will be funeral feasts and rites, and sometimes likely over inside the chamber, that burial chamber.

Noelle: This made me think about what people today might have to say about ancient Roman funerary practices and how that compares to what we do today. I asked student and former de Young Museum community representative, Blair Thomas, what they thought. How do you think these ancient sarcophagi compare to our funerary practices today?

Blair: The only thing I can really compare it to, especially here in the US, is having large funerals, large processions with a lot of people coming and burying ornate coffins is what I can compared to the real world today. I think one thing, especially now with contemporary work, is many people are not necessarily trying to show detail, trying to show their skill, but trying to show emotions, trying to show the work that went into it.

It's very interesting how we've come to that now. We're moving away from just the Western idea of funerals, which is a very small percentage of what it actually is. Not a lot of people actually use those as their idea of what a funeral is supposed to be. It's a very Western idea of what a funeral is supposed to be, of just a very clean, very solemn, very quiet moment when many of the people celebrate. They're loud. It's colorful. It's bright. There's flowers. There's songs. There's dancing. There's music. There's food. There's celebration.

Noel: What are your thoughts on death?

Blair: As last thoughts, just I do appreciate the passage of time that's being depicted. I believe that's something that us here need to really start doing, because I think as a whole, we've kind of have this idea that death isn't something that should be talked about when death is a beautiful thing. It's just the ending of the story, which is not a bad thing. A story can not go on forever.

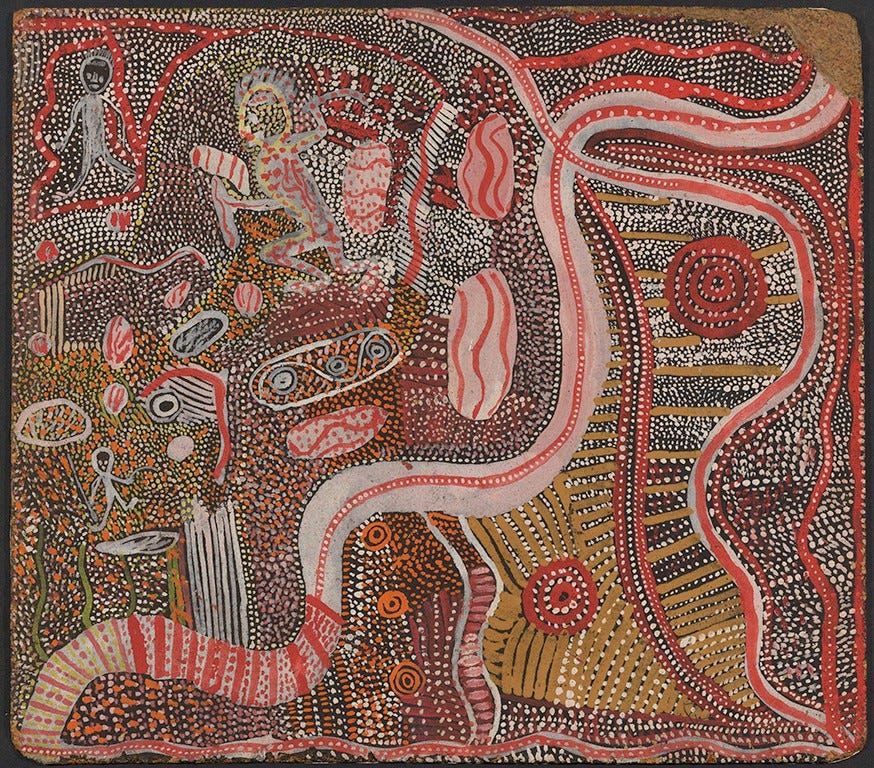

Raquel: Hi, it's Raquel, the density in Johnny Warangkula Tjupurrula's painting, Children's Story (Water Dreaming of Two Children), had me constantly looking at something new. I would say that's what attracted me to this piece. I felt like I couldn't look away for if I did, I would miss something. At first glance, I wanted to capture the piece as a whole and soak it all in. I really liked the pinks and reds that were used as a highlight color, but also saw the whites yellows and blacks standing out. The fields of dots is separated by lines dividing them into sections with random swirls placed in different parts of the piece. I was almost distracted with all the detail that I could have missed the human-like figures in the upper left hand corner and thought that that's how the scene was given its name.

The artist, Johnny Warangkula Tjupurrula, grew up in an Aboriginal community in a desert region in Australia that had a traditional ritual that were intended for initiated men to partake. Initiation rituals may not be shared by people outside the community. So viewers just have to accept that they can't know what it is to be initiated. Some images and ritual objects are not meant for uninitiated boys or even women to see.

An art teacher named Geoffrey Barden had arrived at the settlement that Warangkula lived at to teach at a school and encourage the children to paint, and this led to adults painting as well. Many of them painted stories about their ancestors and their lands. Out of that came Children's Story (Water Dreaming for Two Children). I asked my older sister who is an artist about her thoughts on Children's Story.

Rebecca (Older Sister): One, the color stood out. And then the use of what almost looks like tiling to me. That's what I first said when I first saw this, that there's a lot of dots. Lines, so use of type of lines and dots and such like that. But colors, he has yellow, white, black, and red. So just say, yeah, the use of media and how it's used.

Raquel: She described the piece as . . .

Rebecca: At first, I would not have seen the people at all, which I think is part of the reason as to why the artists did that, is to make it not super viewable and not the first thing you see. First I saw a huge white swirly line in the middle, which I think is their way of distracting the viewer of what's going on. It looks more abstract than it does really look like a scene. But once you look into it further with more time, it looks like a scene.

Raquel: She was really able to see the purpose of the details and use of colors that made this piece as busy as it looks. From her perspective as an artist, she is able to react to Tjupurrula's intentions with understanding. Now, let's hear from Christina Hellmich, curator in charge of the Department of Africa, Oceania and the Americas at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Christina Hellmich: So one of the things that interested me about this piece when I saw it, most of the paintings I had seen that were Aboriginal art paintings were on canvas. So what was interesting about this painting, this is on this composition board and it's actually one of the earlier paintings. I had seen paintings that were created almost a decade later. So the first thing that interested me was also the scale, the scale of the composition and the material. And then, of course, with any Aboriginal painting, there's this wonderful experience of trying to decipher or glean what you can from the composition and in terms of what you make of it.

Raquel: What can you tell us about the dotting technique Tjupurrula used?

Christina Hellmich: The dotting, the over dotting, the lines that you see that are so characteristic of Australian Aboriginal painting, these developed as the dotting in particular and Johnny Warangkula Tjupurrula was one of the first to actually use the dotting that became described as dot paintings. It was used to cover some of the information that they were putting on the paintings in other words. So they were creating landscapes with fields of color. These circular areas might be features on the landscape. So they were using the dots in a way to obscure information that they didn't want people outside of the community to have.

Raquel: Can you tell us a little bit about Aboriginal art?

Christina Hellmich: Well, absolutely. So Aboriginal art, there's amazing cave art. A lot of art was performative. There were compositions on people's bodies during ritual ceremonies. So you have this transference from all these three-dimensional surfaces onto these two-dimensional surfaces. All of these are stories. All of these are community stories. They're stories of creation, stories of land and landscapes. So they're very much, for Aboriginal communities, very narrative. Raquel: Who would've been considered an insider in this community?

Christina Hellmich: So an insider, it might be someone just within a language group or a small family group. It could be a very small network of people that would understand the stories. Also, when Geoffrey Barden first started to work with these men in the community, at first the men started to paint stories that had sensitive information, community information in it. So it might be seen as ritually sensitive. Very quickly, they started to either change, change the visualizations so that they didn't contain that, or they were also encouraged to paint children's stories which were more widely available to people outside the community. Except for maybe some of the very earliest paintings, everything that we see that we would consider Aboriginal art has been created for outsider consumption.

Raquel: Can you talk about the density in the piece from a curator's perspective?

Christina Hellmich: Well, the density, and I think I mentioned that this artist was one of the first men to use these surface layers and over dotting to conceal. So the layers are integral to his formation of the composition. There are fields of color below the dots. So the whole landscape is clear probably to the artists, but to us, obviously the density makes it hard to discern potentially some of the features of a landscape or some of the aspects of the painting.

Raquel: Can you speak about Tjupurrula's history?

Christina Hellmich: So he was born in one place near this lake. He did live there as a child in this desert environment. But later, the family was moved to a mission. There, he worked as a laborer. He was initiated at that time and then was moved to another location for construction work. Finally, I guess it was around the late fifties, he was moved to the settlement of Papunya. That was a settlement that included people from different language groups. These were forced government settlements.

Raquel: Who is Geoffrey Barden?

Christina Hellmich: I think I mentioned that I've been drawing from the work of Judith Ryan and she's the senior curator of Indigenous art at the National Gallery of Victoria. She has advised us in the past, and she's certainly one of the experts in the world on Aboriginal art. She talks about the early establishment of the Papunya art. It's Called Papunya Tula Art Cooperative and the role of Geoffrey Barden. So she talks about his arrival at the settlement. When he arrived, I think I mentioned that he arrived to work at a school. The school had 14 teachers at that time. There were about 1,300 people residing in the settlement. He was a young art teacher who was really enthusiastic about teaching the children in the community. So he started by teaching the children and ended up working really closely with a lot of the adults in the community. This was the beginning of this artist cooperative that went on for decades and certainly catapulted Australian Aboriginal art into the marketplace and into the world art scene.

Raquel: What can you say about the colors used?

Christina Hellmich: For me, they do mirror the colors that would be used on body painting and other forms of ritual painting. So you have ochre, this ochre color, clay, colors that would be possible to create from natural sources. So white, people make from burnt shells and other materials and then ochre and clay. So I guess what I see in this painting are colors that you have seen in ritual painting.

Raquel: Would you like to say anything else about Children's Story?

Christina Hellmich: For me, what's really compelling is thinking about how three-dimensional artworks become two-dimensional. So that these compositions, which were on bodies or actually etched into sand or on the surface of a landscape, then become a two-dimensional composition. So I think that's really compelling. And I think that for so many until the advent of airplanes, Aboriginals were making compositions on surfaces and they're seeing things from a bird's eye view without ever flying or having been in airplanes or above the earth. But this ability to see the breadth of the landscape and in such an incredible way, I find really compelling.

Zune: What you're looking at is a Soundsuit by Nick Cave. When I first saw this artwork, I couldn't make out what it was and why the artists made it. To me, this artwork fits perfectly with the theme density because of how busy it is. The artwork itself seems to have metallic textile with explosive colors from purple to green and gray. The artwork also has many eye-catching patterns like small squares, circles that look like eyes and a pattern that looked like a mustache. What's interesting is that the Soundsuit covers a person inside from head to toe leaving no body parts visible. I'll assume this Soundsuit is tall because all the Soundsuit Nick Cave have made are life-sized and some Soundsuit are even 10 feet tall. But do you know that when Cave made his first Soundsuit the meaning behind it was a lot more serious and dark? His first Soundsuit was made out of his frustration as a black man in America after Rodney King's beating.

Nick Cave: The first Soundsuit came out of frustration and my concern as a black male in America feeling devalued, discarded, dismissed.

Zune: It was made out of twigs that he found on the ground. He connected the twigs to Rodney King's flat body on the ground. When Nick Cave put on the Soundsuit, it made rustling sounds from the twigs and he connected it to the role of the protests where in order to be heard, you need to speak louder. From then, Nick continued to make many more Soundsuit and with some Soundsuit referencing the miter hat form and the KKK uniform to show the ideas of power and its abuse. The Soundsuit you're looking at seems to reference the miter hat worn by the popes and clergy judging from the shape of the head. Cave transformed materials that are often seen as unimportant to represent the experience of being black in America. The reason why the Soundsuit covers a person from head to toe is because Cave wanted to conceal gender, race, and class to have the audience see something without judgment. Looking at the Soundsuit's interesting, but seeing the Soundsuit come to life through movement is even better. Just imagine hearing the rustling sounds the suit makes while seeing this other worldly figure come to life dancing in front of you. On some occasions, Soundsuits are worn by dancers to perform for the public. This makes me wonder how I might feel to put on the suit.

Interviewer: What was it like when you first put on the Soundsuits?

Interviewee: Out of body experience. Well, you put on this costume and you become this thing that's like an animal almost.

Zune: To Cave, putting on the Soundsuit makes you work outside of your comfort zone and you have to be willing to become this figure when you perform.

Nick Cave: It frees you from inhibitions and you have this, again, this opportunity to work outside of your norm and your comfort zone. But it can be tough, very tough. In terms of whether or not you're able to make that transition, you can't put it on and just remain yourself. You have to be willing to transition and become this other thing, whatever that is.

Zune: After knowing all this information, I have a lot more respect for the artist as he was able to take inspiration from something horrible and turn it into something breathtaking. I wonder what other young people like me have to say.

Christie: Hello, my name is Christie. I'm 16 years old.

Zune: What do you think is happening in this artwork?

Christie: What I think is happening is it's a story that has a lot of ups and downs. What I mean is that you don't know where it begins, you don't know where it starts, and you obviously won't know what the uprising or the conflict is because there's so many things going on. You don't even know where to start looking. You don't know what you should examine first because there's so many things that you want to look at, but it's just everywhere.

Zune: What patterns did you notice first?

Christie: The patterns that I noticed first were the squares. It pops out like little waffles to me. Another design that popped out at me is the big circles, how it's like eyeballs looking at me as if it's like a creature of some kind.

Zune: Christie and I can both agree that the patterns, like small squares and eye-like circles, are very striking. What about you? What catches your eye when looking at the Soundsuit?

Noelle: Isn't it amazing how our pieces are literally from different corners of the planet, yet they're all connected because of its visual density?

Raquel: And the cool thing is they all have a meaning and a reason behind all the rich details, patterns, and embellishments.

Zune: To displaying wealth, to hiding secret narratives, to creating a world where race and gender don't divide us. There's definitely something to think about in all of these artworks.