Kehinde Wiley, Ariadne Asleep on the Island of Naxos, 2021. Bronze, 11 13/16 x 29 1/2 x 59 1/16 in., 158.73 lb. (30 x 75 x 150 cm, 72 kg), base: 35 7/16 x 29 1/2 x 59 1/16 in. (90 x 75 x 150 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Museum purchase, Phyllis C. Wattis Fund for Major Accessions, 2022.56.1. © Kehinde Wiley. Courtesy of Galerie Templon, Paris. Photo: Ugo Carmeni

Archaeology is the study of human history and prehistory through the excavation of sites and the analysis of artifacts and other physical remains. It’s an interesting word to use to describe images of Black people at rest, in repose, and embodying the iconography of death. The art of Kehinde Wiley is often rooted in history and this exhibition is no exception. These images modeled after European art are allegories for contemporary Black life, Black possibility, and Black futures, especially in relation to urban existence and state violence. It is the privilege of Blackness that allows Kehinde Wiley to do something no white artist could: present iconography of dead Black people as art.

Kehinde Wiley, Ariadne Asleep on the Island of Naxos, 2021. Bronze, 11 13/16 x 29 1/2 x 59 1/16 in., 158.73 lb. (30 x 75 x 150 cm, 72 kg), base: 35 7/16 x 29 1/2 x 59 1/16 in. (90 x 75 x 150 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Museum purchase, Phyllis C. Wattis Fund for Major Accessions, 2022.56.1. © Kehinde Wiley. Courtesy of Galerie Templon, Paris. Photo: Ugo Carmeni

Choosing archaeology — this academic word steeped in a history of Western imperialism — to describe something so intensely Black is just one juxtaposition among many that the collection creates. In these works, Blackness is both complex and simple, ancillary and at center. Each piece is familiar and foreign for many of the same reasons. We have seen Black bodies lying in this conspicuous way before throughout history. From enslaved Africans to the Tulsa Race Massacre, Michael Brown to the unhoused people asleep under freeways and in parks across the city. And yet, these people have never been afforded sainthood, never been allowed to be treated with the dignity of martyrs, saints, clergy, and royalty. If they are lucky, they are afforded T-shirts and sidewalk shrines as testimony of their transformation into ancestors. They are more likely to be remembered by social media posts, stuffed teddy bears, nativity candles, and bottles of Hennessy than by iconic sculptures in museums of contemporary art.

And what of the forgotten, those whose rest is not afforded and death is not recorded, those who are not even remembered? What happens when the body is all we have left, with no kin to attach it to, and no history behind it? Does it not become object? It feels anti-Black to consider the image of a dead Black person to be beautiful or worthy of reverence. Is it only through symbol that we can understand how our dead should be remembered?

If taken as allegory, the hidden meaning behind each piece is the silence mentioned in the title. It is akin to the silence of complicity when we pass these bodies on the street on our way to the museum. It is the silence we as Black people receive when we complain about systemic anti-Black outcomes across so many domains in this city and so many others. It is the silence of state violence that results in hungry grieving children or youthful bodies lying prone on the concrete in the richest country in the history of the world. It is an excavated silence, from the depths of Black suffering and Western imperialism. It is an artifact both in symbol and in representation of the inevitable consequence of Western civilization itself. Here artist Kehinde Wiley presents physical remains to be analyzed and contextualized and we are all invited to bring our baggage with us and try to understand. We are the archaeologists and though we have a right to, we cannot remain silent.

Installation view of Kehinde Wiley: An Archaeology of Silence, de Young, San Francisco, 2023. Photograph by Gary Sexton. Image courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

We have a right to the dignity shown to the martyrs of others; we have a right to sainthood. I wonder if the experience of witnessing this transformation from person to body, victim to saint, subject to object, casualty to symbol, is as painful for them and theirs as it feels for me. I wonder if they cried when they saw images of their family members lying lifeless on the ground. I wonder if they were discomforted by the witnesses who seemed more moved by the art than by what it represented. More inspired by the actions of the artist than by the suffering of the muse. More fascinated with the lines and form than the subject itself. Black people have always been more valued for our talent and for our bodies than we have been for our ideas.

Kehinde Wiley has replaced the heroic rider of the imperial steed, Sir Francis Drake, Christopher Columbus, George Washington, etc., with his victim, his captive, the inevitable result of his conquest. This horse in the signature piece of the exhibition is American exceptionalism, manifest destiny, and the myth of 1776. It is the legacy of the Atlantic Slave Trade and the colonization of the world that followed. More than a symbol, this rider is a signal of past, present, and future, an antihero whose posture reflects a timeless focus on the individual as both the burden and braveheart of Western imperialism. An Archaeology of Silence is the namesake of this piece, arguably the most breathtaking of the collection. For whiteness in general and white America specifically, the piece is a mirror, an entanglement of glory and suffering, discovery and erasure, settlement and displacement. For Indigenous and Black America it is a symbol of futures that allow us to look to the past to move forward. It is a relic of our origin story, an artifact of our epistemology, and where should it live if not in museums? Where else could our suffering be looked upon with honor and quiet reflection, with reverence and respect?

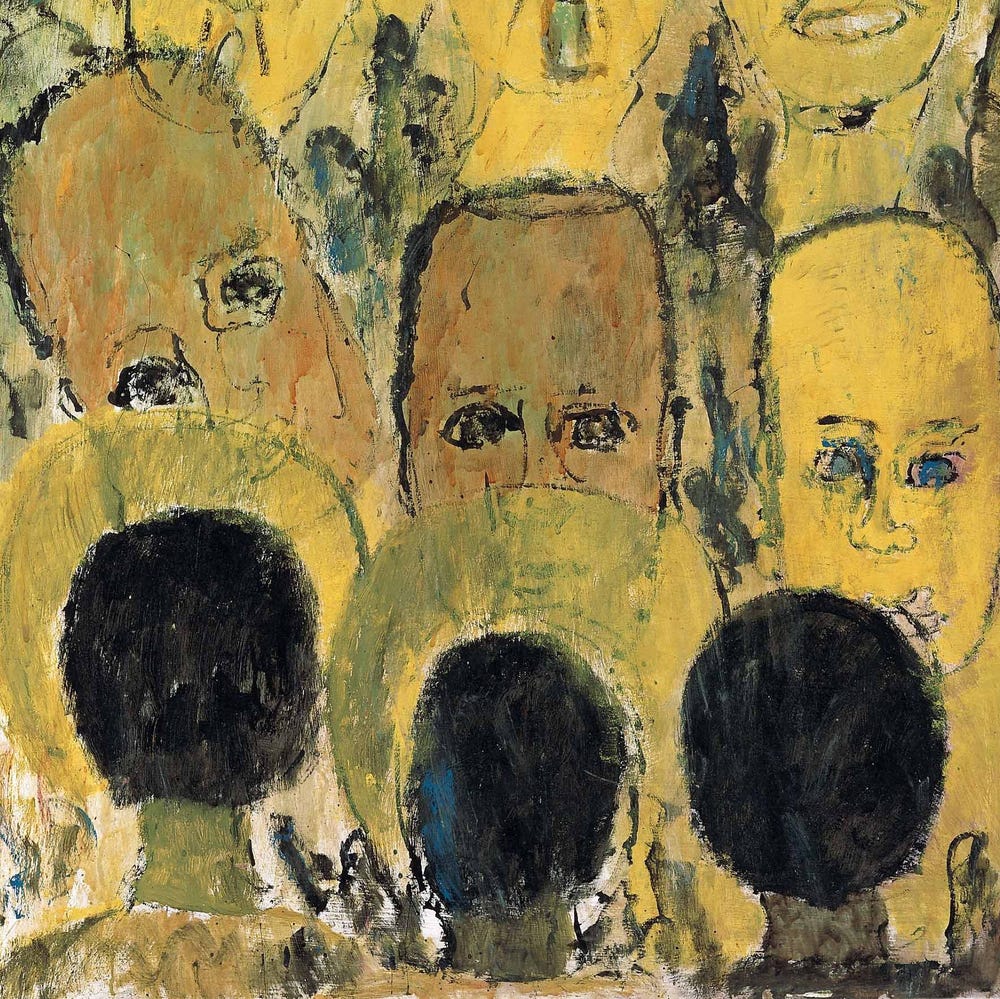

Kehinde Wiley (American, born 1977), Sleep, 2022. Oil on canvas, 69 15/16 x 107 15/16 in. (177.7 x 274.2 cm), Framed: 70 7/8 x 118 7/8 x 3 15/16 in. (180 x 302 x 10 cm). © Kehinde Wiley. Courtesy of Galerie Templon, Paris. Photo: Ugo Carmeni

It is interesting to note that the posture of rest and death are often very similar. Most of the positions we see in art are mere reflections of the ways we move our bodies to fall asleep. Much of the art in this exhibition plays with this blurred line to provoke in the consumer a question about the source of their discomfort. How should we feel about Black people resting? Why should images of Black bodies at rest feel so unsettling? Looking past the postures of the bodies, the majority of the pieces project life and a reverence for the living symbolized by the vibrant colors and vines that appear to hold these bodies in place. But eminent and unspoken in every piece, even without the signal of wounds or blood, is the lifelessness of most of the people lying before us. Why does lifelessness on these Black faces look so peaceful, like a long-awaited well-deserved rest? We live subject to systems producing outcomes that mirror the death Kehinde’s pieces mimic, inequities and injustices that are implied in this deeply moving work. As we walk by these bodies, let us be so moved as to refuse to walk idly by the dying Black people we see. Let this exhibition inspire us to examine the causes of this suffering and to affirm ourselves as the saints we imagine others to be.

Text by Hodari B. Davis, poet, educator, and chief innovation officer of Edutainment for Equity.