’Hoodjabis and Muslim Dandies: How Fashion Intersects with Race, Gender, Class, and Muslim Identity

By Su’ad Abdul Khabeer

October 25, 2018

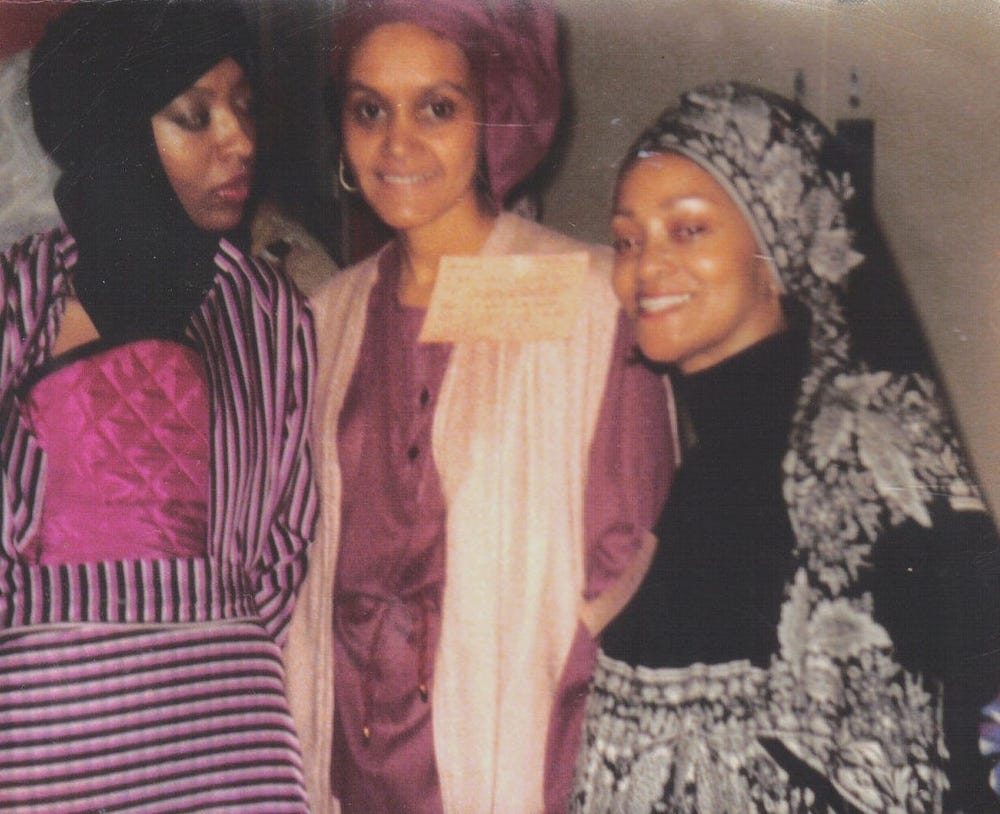

Digging through my mother’s archives, I found a photo of three Black Muslim women at a fashion show in the early 1980s. The women in the photo look fabulous. In the middle stands my aunty, Kareemah Abdul-Kareem, one of the event’s organizers. On her left is a sister (in faith), Fatimah Al-Islam, wearing a tent-style dress: its black neck, chest, and shoulders give way to a black-and-white floral design on its sleeves and lower half. This woman wears a matching khimar (headscarf), the floral print strategically placed, the scarf pinned to the back with the ends hanging past her shoulders. On Kareemah’s other side is another sister adorned in a three-piece fuchsia, black, and white striped suit wearing a black turban tied over a black scarf that wraps around her ears and neck. Kareemah wears a silky drawstring plum tunic under a long silky beige vest. Her plum scarf is tied to the side, the ends fanning out like a flower over her left ear, her right hoop earring exposed. Kareemah also wears an oversized index card on her vest’s lapel that carries a description of the outfit and its designer’s name.

Aunty Kareemah and friends, early 1980s. Courtesy of umisarchive.com

This photograph tells an important story about Muslim fashion history in the United States, one that connects to contemporary Muslim fashion in three key ways. First, it contradicts a tired mainstream narrative that being fashionable is something new among Muslim women in this country. Plenty in this photo, style-wise, could be drawn straight from a news feature about current Muslim “fashionistas,” evidence that today’s Muslim modest fashion—like all fashion—is indebted to the styles of yesteryear. Second, differences in how each Muslim woman in the photo is dressed challenge mainstream tendencies to regard the hijab as monolithic and uniform. Muslim women cover their bodies and heads in myriad ways, but it is often presumed that the hijab appears only as a burqa or as a scarf wrapped in a manner associated with the Middle East. Lastly, the photo challenges stereotypes outside and within the Muslim community. Outside Muslim communities, it refutes mainstream demonization of Muslims in the United States as “foreign” and threatening; within Muslim communities, it questions hierarchies of racial and ethnic privilege within the US Muslim population.

The author (in white) with her mother (in pink) in the 1980s at India House, a restaurant that was the site of many celebrations for Black Muslims in Brooklyn. Photo courtesy of Majida Abdul-Karim

The racialization of Muslims in the United States and elsewhere is a defining characteristic of the contemporary moment. Along with many others, I use the term anti-Muslim racism to describe forms of discrimination that specifically target Muslims because of their religion in racial ways. Such discrimination often focuses on what Muslims “look” like as part of a wider depiction of their “culture” as alien and threatening to the national and sometimes Western, or modern, culture. One consequence of such racism is the erasure of Black Muslim communities from mainstream narrations of the US Muslim experience. Black Muslim communities are a central component of the history of Islam in the United States, and their existence contradicts the positioning of Muslims as an immigrant threat. My mother’s archived photo recovers a slice of that missing story, demonstrating the prominence of Black Muslims within the Muslim US American population and as pioneers of US Muslim fashion.

Muslim Cool

My interest in Muslim fashion history is connected to my research on what I call Muslim Cool: a way of being and thinking about what it means to be Muslim in the United States. Muslim Cool engages blackness, through hip-hop, to counter anti-blackness in Muslim communities and in broader US society. I found Muslim Cool among young US Muslims, age eighteen to thirty (and even in their forties), who are Black, South Asian, and Arab US Americans engaged in hip-hop-based activism. Muslim Cool manifests in ideas and activism but also in style and fashions that draw from broader Black cool, a globally embodied form of resistance based on independent sets of aesthetic norms and ideals. My examination of Muslim Cool led me to look at fashion as a way of understanding Muslim identity: what is it composed of? what are its evolutions and contestations? and how is it represented through style? I came to understand that the US Muslim fashion landscape is a complex terrain formed by the intersections of race, gender, and class.

Artists such as Queen Latifah and Erykah Badu have popularized such head wraps as part of the Afrocentric hip-hop aesthetic.

In my book Muslim Cool: Race, Religion, and Hip Hop in the United States, I look at one particular headscarf style—a scarf tied in a bun at the back of a woman’s head—that is also tied up in the complexities of race and class in the United States. Rooted in the African diaspora, this style has a history of use among enslaved and free Black women, who used headscarves in utilitarian ways: to preserve braided hairstyles; for ritual use in Christian, Muslim, and Vodun ceremonies; and as a form of sartorial opposition to white US American norms. Today, contemporary Black women, from a variety of religious orientations, use this and other, more elaborate wrapping styles in a display of Afrocentricity and cultural pride, while artists such as Queen Latifah and Erykah Badu have further popularized such head wraps as part of the Afrocentric hip-hop aesthetic.

Photo by Evan Brown Photography

When worn by Black Muslim women, this style signals both racial pride and religious devotion. Such a connection is so powerful that one of the young Black Muslim women I worked with described feeling “odd” when she wore her headscarf in other styles not linked to the Black US Muslim experience. Another young Black Muslim woman, attracted to the style for its relationship to Black cool and popular culture, wore it to reaffirm the connection between her Muslim and Black selves. This link, between Black and Muslim identity, intervenes in the circulation of anti-blackness in US Muslim communities, in particular the racialized norms that conflate ethnic and national background with religious authority. This means that US American Muslims who have roots in the Middle East and South Asia are generally considered more authentically Muslim. The racial politics of US Muslim communities take the view that, globally, Arab Muslims are typically accorded high status for their links to the land of Mecca and for speaking the language of the Quran (this is often expanded to include Muslims from South Asia). The privileging of lineage from these countries casts the religious practices of Black Muslims as inauthentic and even religiously suspect.

’Hoodjab/’Hoodjabi

Some non-Black US American Muslim women also wear this headscarf style because they think it is cool. Accordingly, I sometimes refer to it as ’hoodjab/’hoodjabi, a term I learned from a young South Asian US American Muslim woman whose white female supervisor referred to her this way. A play on the term hijabi, which was popularized by young English-speaking Muslims to refer to women who wear a headscarf, ’hoodjabi refers not only to one’s religious practice but also to one’s race and class. Specifically, it addresses the suturing of Black identity to underclass socioeconomic status. Because of these connotations, non-Black women wearing this style can be understood as a form of cultural appropriation—adopting a cultural practice that is not one’s own without any real regard for or relationship to the people who created it.

They were drawn to this particular scarf style because they saw it as a symbol of the Black experience of righteous struggle against injustice.

But in the context of Muslim Cool, this assessment lacks nuance. I discovered that the ’hoodjab reflected not only non-Black young Muslim women’s desires to be cool but also spoke to their commitments to social justice. These young non-Black Muslim women were activists working alongside Black communities on issues of racial and economic inequality and challenging anti-Black attitudes in their own ethnic Muslim communities. They were drawn to this particular scarf style because they saw it as a symbol of the Black experience of righteous struggle against injustice. As one young woman put it, wearing the style was a way to connect to a “larger social movement” for justice. I’m not arguing that their activism places their choice of scarf style above critique, but that their choice acts as a stylistic conduit initiating the difficult work of interracial solidarity.

The multiplicity of a headscarf—its simultaneous function as something cool, a symbol of social justice, a sign of Black pride and cultural belonging, and a marker of religious devotion—expresses what is productive and problematic about fashion in general, and Muslim fashion in particular. The Muslim fashion landscape is complex ground because it reflects the multifaceted identities of Muslims in the United States and elsewhere. In this instance, the way one ties her headscarf demonstrates how expressions of Muslim womanhood reflect questions of religion and gender but also race, class, and popular culture.

Muslim Dandies

Similar themes arose in my studies of a cohort of men I call Muslim dandies. The dandy is a well-known fashion archetype: a man who dresses well, and with some flair, as a means to claim a higher social status. In classic depictions the dandy is a white man, but there is also a tradition of Black dandyism (as documented by scholars like Monica L. Miller). Historically, Black dandies, donning embellished elite European dress, used style to challenge racial norms that dehumanized Black people. Recently, Black dandyism has made a contemporary and transnational resurgence.

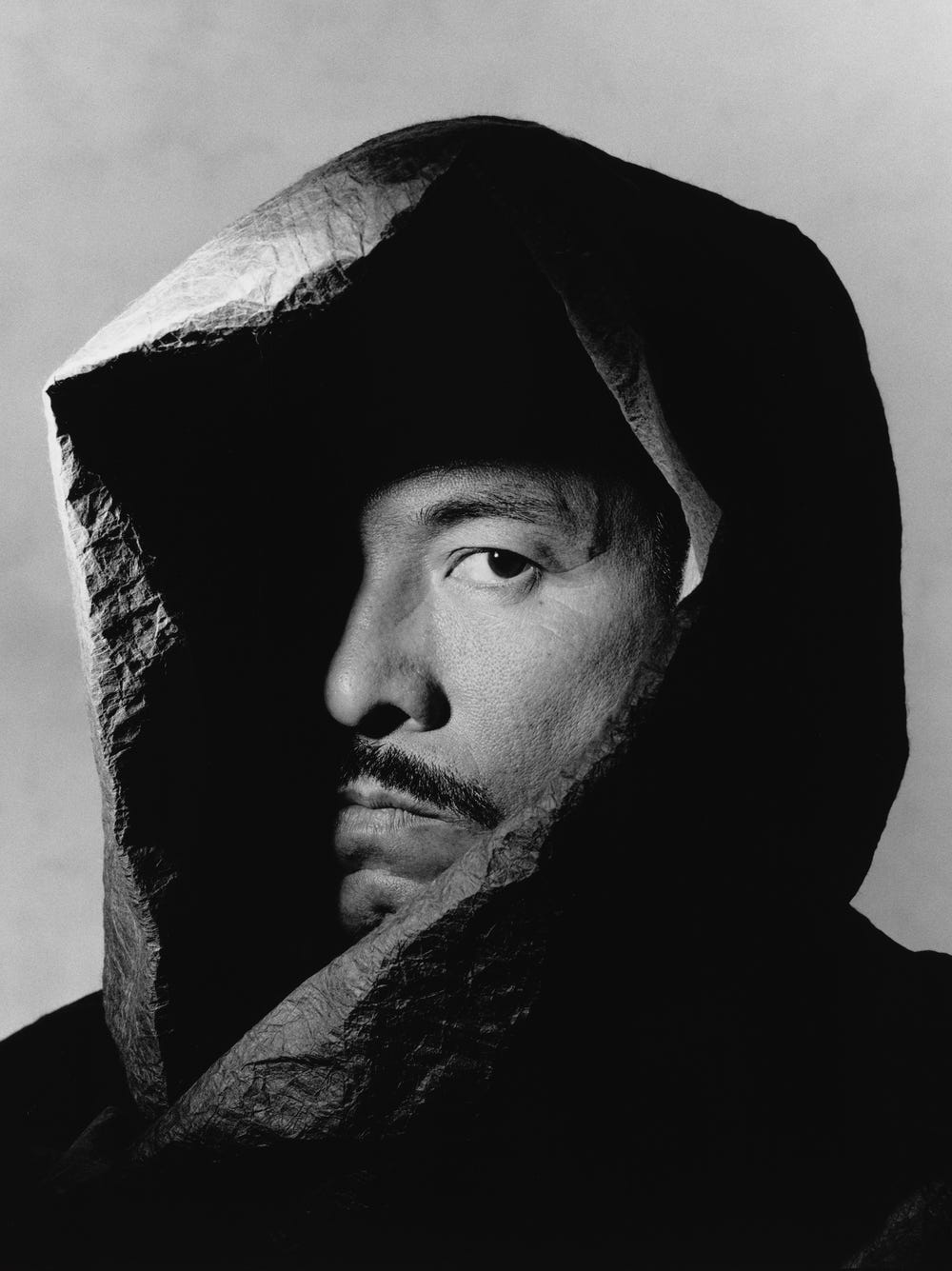

Photo by Evan Brown Photography

In her exhibition The Dandy Lion Project, curator Shantrelle Lewis focuses on cohorts of Black men in the United States, Europe, and Africa who are remixing Edwardian-era, Victorian-era, and early twentieth-century Americana styles as an expression of Afro-diasporic masculine identity. Self-consciously using colors, prints, fabrics, hemlines, cuts, and accessories, Black dandies don styles associated with white masculine power but remix them to challenge rather than mimic whiteness, making Black dandyism a form of racial resistance and redemption through style.

Muslim dandies enter the dandy landscape at the site where blackness and Islam meet—their dress acts as a form of racial and religious resistance and redemption. As part of my work on Muslim Cool, I encountered Muslim men, mostly Black Americans, who were raised in the “’hood” and used style to counter the well-worn image of young working-class men of color as thugs—hypersexual, hyperviolent, and nihilistic. The styles of Muslim dandies matched that of broader Black dandyism—through items such as tweed suits, pocket squares, and velvet slippers—while also including elements that are distinctly Muslim, such as non-silk ties (in accordance with religious law) and cuff links in the shape of the Prophet Muhammad’s sandal, a Muslim sigil.

This stylistic mix-and-match reflects Muslim dandies’ eclectic influences. These men identified their own style as a return to a tradition of looking good practiced by an earlier generation of men: their fathers and uncles, as well as the “suited and booted” Muslim men of the Nation of Islam (NOI). Founded in 1930, NOI is a Black Muslim organization best known for championing Black self-determination. Its national and international impact is driven in part by its emphasis on distinct ways of thinking and forms of living, including dress, that directly confront white supremacy. The men of the NOI are distinguished in Black communities for being impeccably dressed, either in the uniform of the Fruit of Islam or tailored suits with bow ties and well-shined boots. They challenge ideas of Black inferiority through sartorial Black excellence. The Muslim dandies I interviewed were also influenced by other types of stylish Black men, such as street hustlers and early hip-hop figures known for wearing suits. They identified their style as a return to a Muslim tradition of looking good, or ihsan, in which attention to style is a form of spiritual discipline and a demonstration of God’s magnificence.

Photo by Evan Brown Photography

The relationship between hip-hop music and US American Muslim communities is a rich one. From its inception over forty years ago, hip-hop music has drawn from the social justice teachings of Black US American Muslim communities in crafting its own principles of justice and equality. Many of the men I interviewed, converts to Islam, were introduced to the faith through hip-hop music and culture. As with all the young Muslims I have worked with, the principles of social justice embedded in hip-hop music and culture had helped these men shape their religious identities.

Yet upon entering Muslim communities, these men discovered that the things that had attracted them to Islam—its link to the Black experience and the urban, Black styles associated with it—did not garner them authenticity and authority as Muslims. For example, one Muslim dandy from Chicago told me he was considered a religious authority among his friends when they all first converted and was often asked to lead their prayers. But once he began to wear a three-piece suit rather than an Arab thobe (long male dress), his friends opted for a prayer leader who did not have as much religious training but who “looked the part.”

In many Muslim communities, men who are religious authorities tend to wear clothing that originates in cities like Cairo or Karachi rather than any US city. Black Muslim male leaders often adhere to this standard to bolster their religious authority. The need to “look the part” is tied to the ethnocentric and anti-Black norms within many US Muslim communities described earlier. In such communities, authority is given to Muslim men who wear the thobe or the South Asian shalwar kameez and denied to those who wear hip-hop gear or three-piece suits.

In the face of these norms, both those that cast urban men of color as thugs and those that question the legitimacy of Black Muslim practice, Muslim dandies’ dress is a significant intervention. It challenges mainstream ideas of Black pathology as well as narrow notions of Muslim identity. Similar to the stylistic innovations of Black Muslim women, they are designing an alternate set of stylistic norms that celebrate rather than denigrate Black Muslim identities.

From headscarves to sandal pins, stylistic choice plays a deeply significant role in Muslim self-fashioning in the United States. For both women and men, fashion is a form of self-expression and cultural intervention, a vehicle to explore and affirm the connection between racial and religious identity. It also is a means to contest which hegemonic forms of exclusion, like anti-blackness, are challenged and reproduced. Some might be inclined to frame these styles as wholly new, but contemporary Muslim fashions build upon and reiterate the stylish Black and Black Muslim past, from historic Black dandies to late twentieth-century Black Muslim women trailblazers, like my Aunty Kareemah.

This text was adapted from an essay by Su’ad Abdul Khabeer included in Contemporary Muslim Fashions, the catalogue for the exhibition of the same name, on view at the de Young through Jan. 6, 2019.

Su’ad Abdul Khabeer is a scholar-artist-activist who uses anthropology and performance to explore the intersections of race and popular culture. Su'ad is currently an associate professor of American Culture and Arab and Muslim American Studies at the University of Michigan. She leads Sapelo Square, the first website dedicated to the comprehensive documentation and analysis of the Black US American Muslim experience.