Gathering of the Clans: Tavernier’s Encounter with the Lakota

By Arthur Amiotte

April 7, 2022

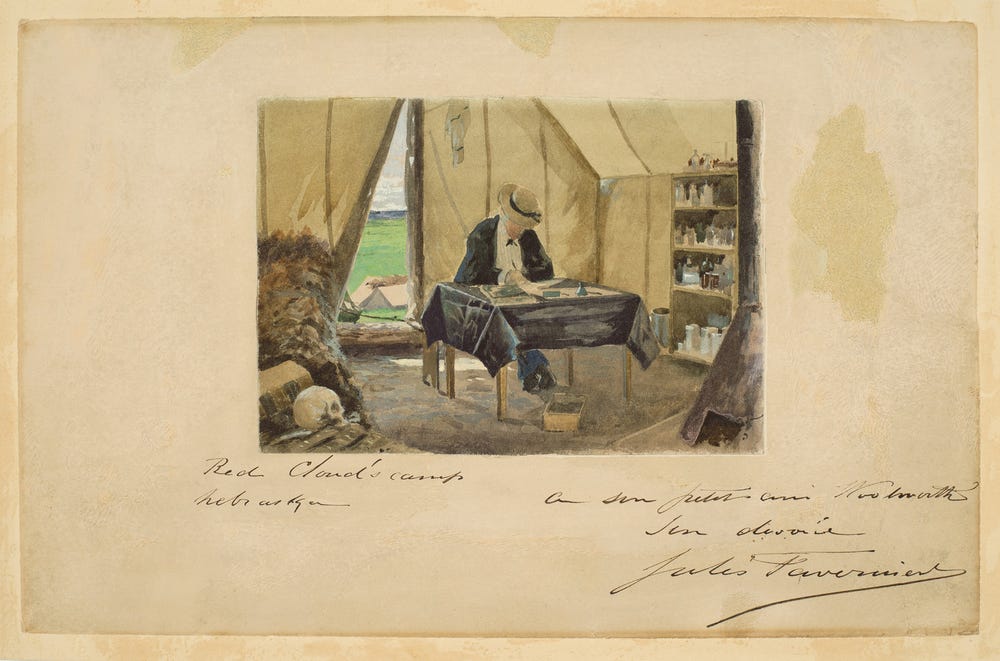

Artist Jules Tavernier’s encounter with the Lakota (also known as the Sioux) in 1874 came at a critical time in the tribe’s history. The painting Gathering of the Clans, ca. 1876, is an interpretation of what Tavernier saw during his stay at the Red Cloud Agency in May of that year. The depicted scene took place in northwestern Nebraska, a state since 1867. It was the site of a US military installation to warehouse (in a newly built stockade), administer, and distribute the provisions of the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie between the United States and the Sioux. According to a March 1874 census report, about 6,900 people of the Oglala band of Lakota (not the whole Sioux Nation), under the leadership of Red Cloud, had already been in residence there since 1871, along with 1,200 Cheyenne and 800 Arapahoe, both allies of the Lakota. This enclave camped in the remnants of tipis made of bison hide and agency-issued canvas, forming a stationary village designated by the government as the Red Cloud Agency, and was thus a much more significant community than Tavernier’s watercolor Red Cloud’s Camp, Nebraska, ca. 1874, suggests.

Jules Tavernier, Red Cloud's Camp, Nebraska, ca. 1874. Transparent and opaque watercolor on paper, 8 1/2 × 13 in. (21.6 × 33 cm) Framed: 14 1/4 × 18 3/4 in. (36.2 × 47.6 cm). Collection of Nancy and David Ferreira.

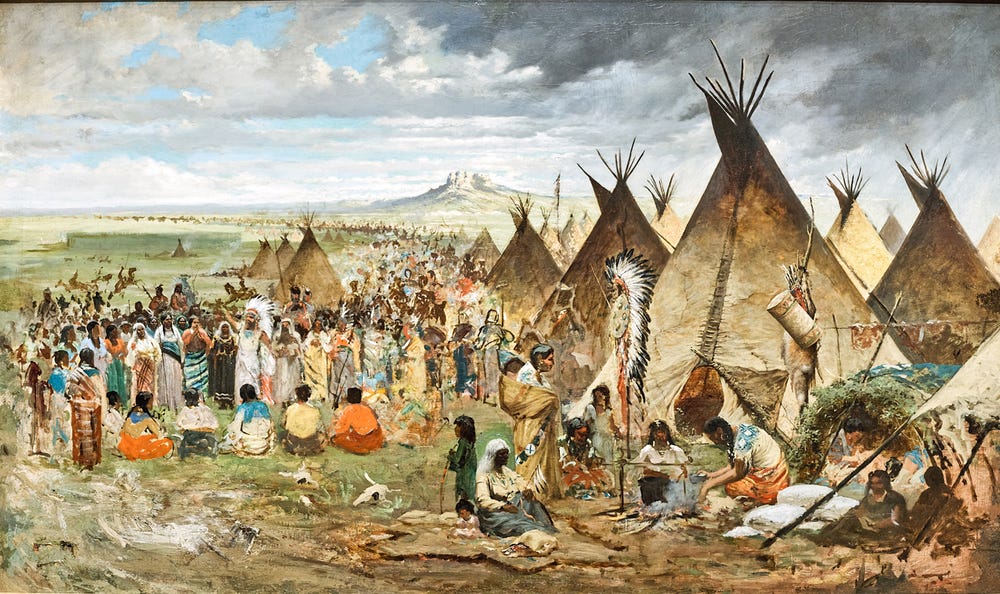

In Tavernier’s grand oil painting Gathering of the Clans, also known as Lakota Encampment, a massive parade of mounted people advance from the distance. These “gathering clans” may have more accurately been representatives from some of the bands at large on the plains, who were still leary of appearing at the agency. The advancing mass also may have been a contingent from the Spotted Tail Agency of Lakota, located 43 miles northeast of the Red Cloud Agency.

Jules Tavernier, Gathering of the Clans, also known as "Lakota Encampment," ca. 1876. Oil on canvas, 41 × 69 in. (104.1 × 175.3 cm), Framed: 48 1/2 × 76 1/4 × 5 1/2 in. (123.2 × 193.7 × 14 cm). The Oakland Museum of California, The Oakland Museum of California Kahn Collection. Photograph by Randy Dodson

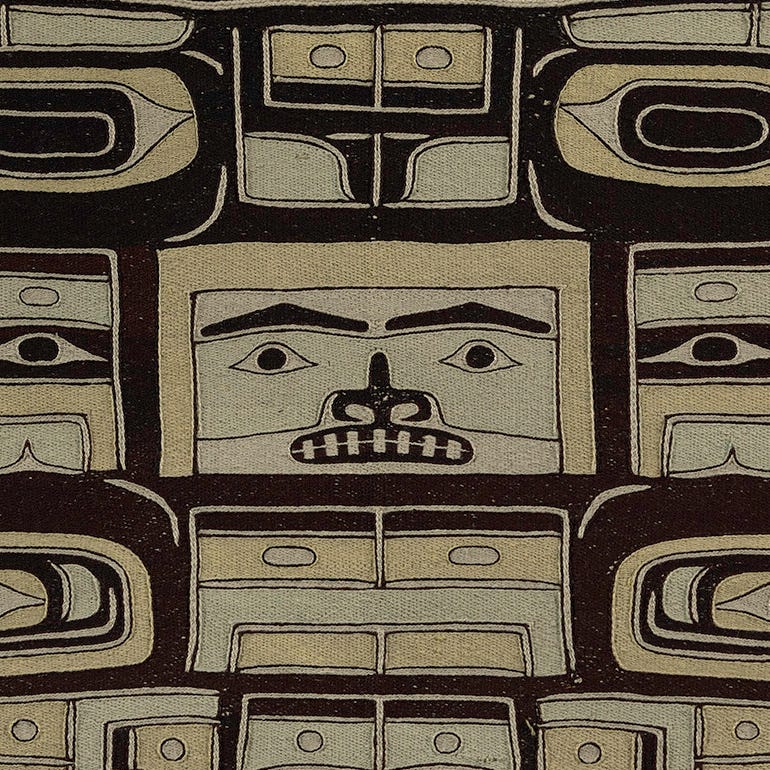

When Tavernier visited, the Lakota were nearing the end of their tenure, evolved over millennia, as free, far-ranging gatherers and hunters of the bison on the northern plains; the US government and white settlement posed threats to their very existence. At the time, the Lakota were composed of seven major bands and sub-bands, ranging in size from hundreds to thousands of people. The bands and sub-bands, each with its own cohort of leadership, were related through kinship and common cultural lifeways, languages, and customs as gatherers and mobile bison hunters. They shared an ethos and belief that they were descended from the same original, spiritually and mythologically defined ancestors; their traditions were generated over thousands of years and embedded in a shared Lakota tribal heritage.

These sub-bands and bands spent the major part of the yearly seasonal cycles separated, hunting bison and other wild game to sustain the size of their group. They traversed the vast yet familiar territories of the northern plains, camping for longer periods during the winter, when they were snowbound for months. When spring and summer returned, these bands might meet, and this mutual Lakota ancestral knowledge of the world was celebrated in great tribal reunions, such as the Sun Dance ceremony. In Tavernier’s painting, the tribes are seen camping together in welcome reunion, shared hospitality, and customs of social renewal and bonding.

The Sun Dance ceremony was an expression of faith and a solemn occasion. Tavernier’s depiction of the ceremony, Indian Sun Dance—Young Bucks Proving Their Endurance by Self-Torture, published in Harper’s Weekly (January 2, 1875), is on view in the exhibition. The wood engraving is in the genre of journalism illustrations of this period that sensationalized what was perceived to be the “savagery” of the Western tribes, influencing public opinion about how the “Indian problem out West” should be dealt with. Tavernier treated many of the subjects in the scene with historical accuracy, including the tribal members wearing both Indigenous and European attire, but he took artistic license with others, conflating events that occurred over several days into this last day of a complex and episodic drama.

The structure in the center left of Gathering of the Clans is identified as the sacred lodge of the Sun Dance. As it’s portrayed here, appearing behind a nearby tipi and in perspective from the vantage point of the artist, it would have been extraordinary in height and scale and an exaggeration of historical reality, similar to the exaggeration of the interior in the Harper’s Weekly engraving.

The male figure addressing the group of women in the foreground was not the more famous historical Sitting Bull of the northern Lakota but an Oglala lieutenant headman by the same name. He was probably one of the appointed heralds or official announcer-messengers addressing the women about details of the forthcoming Sun Dance ceremony.

The structure in the lower left, next to the tipi, is not a sweat lodge but rather a temporary structure for shading and sheltering visitors and guests during large gatherings. The presence of a metal kettle and cloth sacks of flour on the right accurately portrays the effects of agency existence. Tavernier also fittingly represented a shield and headdress on a pole in front of a tipi, signifying it as the residence of a prominent leader and thus indicating it should be approached with appropriate protocol. Figures in the painting are correctly depicted wearing Euro-American garments. This amalgamation of cultural materials, such as tailored garments, patterned blankets, and colored cloth dresses, attests to their availability as government treaty annuities and at trading posts located near the agency and frequented by the Lakota.

Tavernier rendered the landscape and sky in Gathering of the Clans, with extraordinary skill and technique, capturing the dramatic presence of the Crow Butte landmark in the distance, still a spectacular and dominant feature of the region. Today it towers above cultivated fields of wheat and pastures dotted with Black Angus cattle.

Tavernier made sketches that reflect the impacts of rapid expansion of white settlement and the US government’s forced relocation of Indigenous communities from their ancestral lands to reservations, scenes that later became paintings in his studios in California and the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi. Sold for $1,000 in 1884, Gathering of the Clans is one of Tavernier’s largest canvases, though he never fully finished it. Tavernier completed at least 30 paintings of Native Americans over the course of his 18-year career. While they were often colorful scenes of ceremonies and gatherings, they also visualized the struggle of Indigenous peoples to maintain sovereignty over the land and resist settler encroachment.

Text by Arthur Amiotte, Oglala Lakota artist, art historian, and educator from the Pine Ridge Reservation, South Dakota.

Jules Tavernier and the Elem Pomo is on view at the de Young from December 18, 2021 through April 17, 2022.