From Patrick Kelly to Kanye West: Reappropriating and Commodifying Racist Memorabilia

By Abram Jackson

October 18, 2021

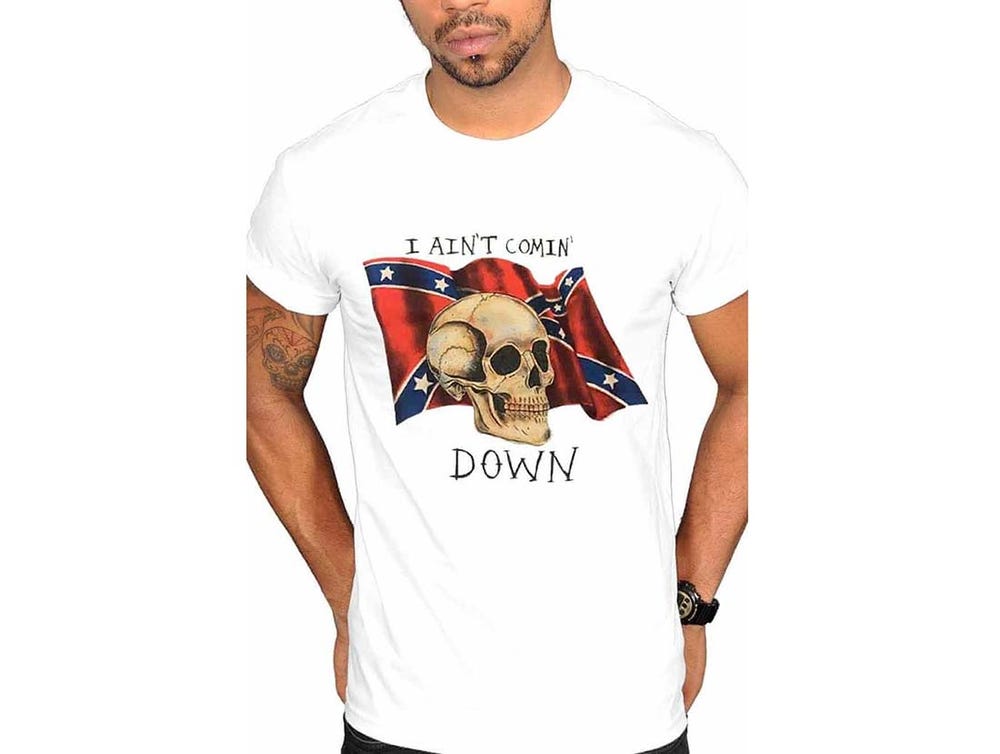

As I walked into the arena in the fall of October 2013 for Kanye West’s Yeezus tour, my heart sank at the sight of the first merchandise booth. There it was, the Confederate flag emblazoned on T-shirts and jackets, with a long line of mostly Black fans waiting to pay for the overpriced merch (cue the Twilight Zone music). I could not figure out how this reappropriation was going to work, and I did not personally feel empowered by the twenty-first-century hip-hop use of the symbol of secession, enslavement, racial terror, and white supremacy. For the entirety of the concert, I was distracted by Kanye’s choice of tour merchandise. Later, in an interview, Kanye West shared that “the Confederate flag represented slavery in a way . . . that’s my abstract take on what I know about it. So I made the song “New Slaves,” so I took the Confederate flag and made it my flag. It’s my flag now. Now, what are you going to do?”

Kanye West tour t-shirt. Photograph PR / TheGuardian.com.

Patrick Kelly’s story is one of awe and inspiration. This African American Southerner, who was born in Vicksburg, Mississippi, ultimately created an artistic vision that permeated Paris in the 1980s. His genius led to lucrative ready-to-wear opportunities that no other African American designer achieved at that time. In 1987, Kelly signed a multimillion dollar deal with Warnaco, which would enable him to manufacture his clothes to be distributed worldwide. Unfortunately, Kelly passed away from complications related to AIDS before his global fashion empire was able to come to fruition. As you engage with Patrick Kelly: Runway of Love, you will come across a variety of racist memorabilia that Kelly incorporated and commodified into his fashion lines. Depending on your positionality, you might experience those images differently. You may be triggered, traumatized, unaffected, curious, confused, and have an infinite amount of other feelings. The historical context of the images that Kelly used in his fashion is a vestige of the Reconstruction era in the United States following the 1863 Emancipation Proclamation, which attempted to end enslavement after the Civil War, even though it would be several years until the official end of enslavement. The South’s response was an all-hands-on-deck attack on Blackness. Just as African Americans began to hold positions of power in politics, business, and education, white racial terror and violence used to uphold enslavement transmuted into what is commonly called Jim Crow. This is the historical time frame that generated the Ku Klux Klan and White Citizen Councils, in addition to a racist media response that included the first feature-length film ever, D. W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation (ca. 1915). This important cinematic breakthrough of technical, narrative, and special-effect advancement portrayed Blacks as shiftless, lazy, and animalistic, and argued that granting freedom to Blacks and incorporating them into the fold of society as racial equals was a grave error. The film’s premise is the division of two families, one Union and the other Confederate, post–Civil War, and was the foundation of powerful, controlling images used to dehumanize Black people. In Donald Bogle’s Toms, Coons, Mulattoes, Mammies, and Bucks, he describes the characteristics and purpose of specific portrayals of African Americans. The pickaninny image, which Bogle describes as a character who was “a harmless little screwball creation whose eyes popped, whose hair stood on end with the least excitement and whose antics were pleasant and diverting” (Bogle 16), appears under the category of “coon.”

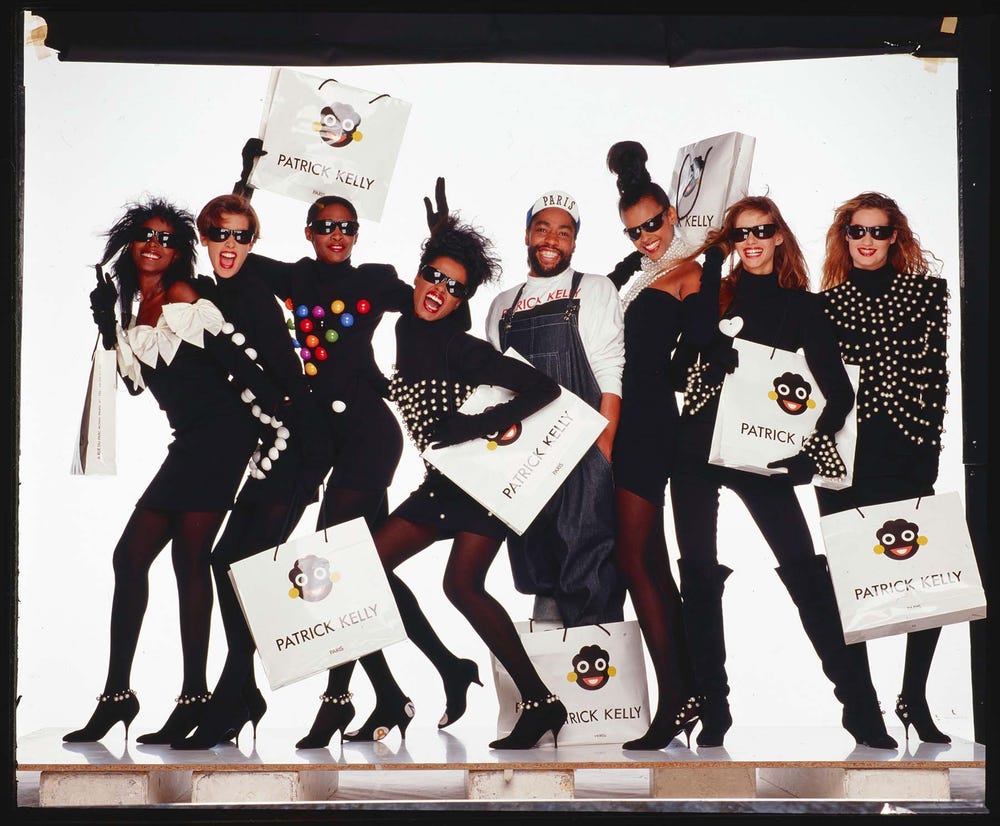

Patrick Kelly’s favorite Black American racist memorabilia was the golliwog, which is a subcaricature of the coon and pickaninny. The story of this caricature, like Kelly, has both American and European connections. The golliwog was the name of a blackface minstrel doll in Florence Kate Upton’s 1895 book, The Adventures of Two Dutch Dolls. Though the book was published in London, the golliwog doll was inspired by the pickaninny minstrel dolls that Upton played with when she lived in New York. Ultimately, the tale and the golliwog were a hit in England and were used commonly in storybooks, also leading to the mass manufacturing of golliwog dolls by several toy companies (Pilgrim). During the late eighties, Patrick Kelly was known for incorporating a golliwog image on dresses, bags, hats, and stickers, just to name a few items. He would sometimes give them away at shows and to random people on the street. On his tombstone, a golliwog resides above a bright red heart. Arguably, the intention of any controlling image is to dehumanize. In this case, a golliwog suggests that Black people are childlike and implies that a paternalistic relationship with white America is necessary for order. So why might Kelly be drawn to the image? Kelly once said in an interview, “If we can’t deal with where we’ve been, it’s gon’ be hard to go somewhere.” Kelly was the first Black American fashion designer to sign a multimillion-dollar fashion deal. His designs and work were going to be globally distributed, and he was and continues to be heralded for his dynamic artistry.

Patrick Kelly’s tombstone depicting the golliwog. Pierre-Yves Beaudouin / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 4.0

The reappropriation of symbols and words by those targeted by racism themselves does not have the same sting as when those images and words are used by people in power. One easy example is the N-word. A Black person saying it to another Black person in the spirit of reappropriation does not hurt in the way that it does when a white person says it to a Black person. In fact, for many African Americans, the remix of the word is empowering and a reflection of an insider signification of camaraderie. But what happens when that reappropriation goes mainstream? Arguably, it often opens the door for global use of words and, in the case of fashion, a global use of the symbol in everyday wear. This might be why Warnaco prohibited Kelly’s use of racist imagery in their fast-fashion production. In thinking about Kanye’s Confederate flag merchandise, I had a similar concern. I could not imagine seeing a young white fan, or Black fan for that matter, in the streets of San Francisco donning a jacket bearing a Confederate flag. I imagined that it would go terribly wrong when encountering a Black person of a certain generation. I worried that it would inflict deep pain, anguish, and harm on the Black people they encountered. This might be the danger of reappropriation in the fashion world; however, a fashion exhibit is the place for a deeper dive.

Patrick Kelly collection. Photograph by Oliviero Toscani. Courtesy of the Estate of Patrick Kelly. Scan by Randy Dodson / Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

The beauty of a museum exhibition is that it allows for context and conversation about cultural phenomena that need more time and attention than a thirty-second encounter on the street. Museums work to contextualize and curate the story of what was happening and ask the question, what do you think? This is the exciting part of having Patrick Kelly’s fashion and legacy available for view at the de Young. It allows visitors to understand Kelly’s hopes and to investigate the implications of those images. In thinking about the power of racist symbols, words, and iconography, performance studies scholar E. Patrick Johnson asserts, “When white Americans essentialize [B]lackness, for example, they often do so in ways that maintain ‘whiteness’ as the master trope of purity, supremacy, and entitlement, as a ubiquitous, fixed, unifying signifier that seems invisible. Alternately, the tropes of Blackness that whites circulated in the past—Mammy, Sapphire, Jezebel, Jim Crow, Sambo, Zip Coon, pickaninny, titute, rapist, drug addict, prison inmate, etc.—have historically insured physical violence, poverty, institutional racism, and second-class citizenry for [B]lacks” (Johnson 4). This assertion leads me to wonder, what does it mean when a Black person has the power to circulate racist images or symbols to the masses? Whether it is for reappropriation or satire, does it perpetuate the many forms of violence against Blackness or does it empower and topple white supremacy? These are the questions that Patrick Kelly: Runway of Love inspires, and I hope you consider them in experiencing the exhibit.

Works Cited

Bogle, Donald. Primetime Blues: African Americans on Network Television. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2002.

Johnson, E. Patrick. Appropriating Blackness: Performance and the Politics of Authenticity. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2004.

Pilgrim, David. “The Golliwog Caricature.” Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia, Ferris State University, November 2000, https://www.ferris.edu/jimcrow/golliwog/

Wilson, Julee. “Kanye West Explains Those Confederate Flag Concert Shirts.” HuffPost, October 29, 2013, https://www.huffpost.com/entry/kanye-west-confederate-flag-shirt-explained-_n_4173200

Text by Abram Jackson, ethnic studies and humanities educator.

Patrick Kelly: Runway of Love is on view at the de Young from October 23, 2021 until April 24, 2022.