Carrying Baskets: The Seeds of Pomo Life in California

By Sherrie Smith-Ferri

December 16, 2021

This gleaming woven vessel with its spiraling design is an archetype of Pomo basketry. Pomo women created and used a variety of baskets to gather and prepare native plant foods for themselves and their families to eat. Some of the most important of these foods were the seeds from native grasses and wildflowers. Though small, these seeds are loaded with flavor and high in fiber, oil, complex carbohydrates, and protein. They served as seasoning, snack, hearty porridge, and travel food. Their modern equivalent might be the PowerBar.

Carrying basket, early 20th century. Fiber - Willow And Redbud Shoots, Sedge Grass Root, 19 1/2 x 19 x 19 in. Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Gift of Mr. H.H. Welsh, 51973.1. Photograph by Randy Dodson

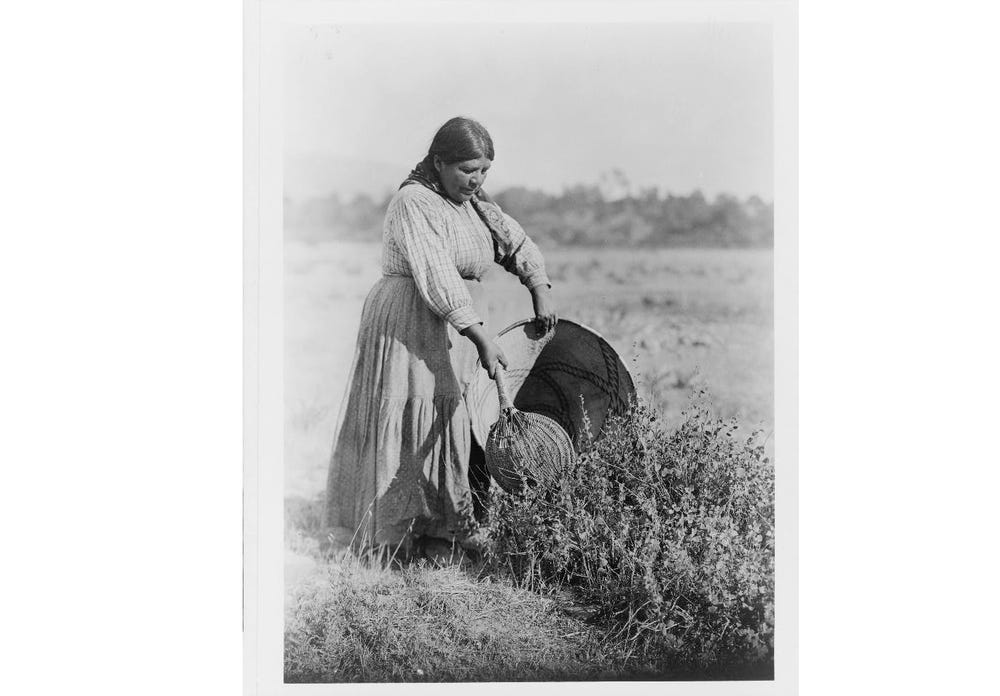

Beginning in early summer, Pomo women harvested different types of seeds, from more than thirty species of plants, as each ripened in turn. This particular type of basket—large-mouthed, tightly woven, and conical—was called a “carrying basket.” It was paired with a big, handled, spoon-shaped, twined seed beater. Together these two tools were employed by Pomo women to gather vast quantities of edible seeds. Women hit stands of mature plants with the seed beater, knocking their ripe seeds into the mouth of the carrying basket held below, slowly filling it. During this process, some seeds fell outside the carrying basket onto the earth, increasing the spread of these food plants and helping to ensure their future abundance. After long hours spent gathering, women would place their full basket of harvested seeds into a net held by a woven strap. The net secured the heavy basket against the wearer’s back, while the strap helped suspend the basket from the wearer’s forehead or shoulders as she walked home.

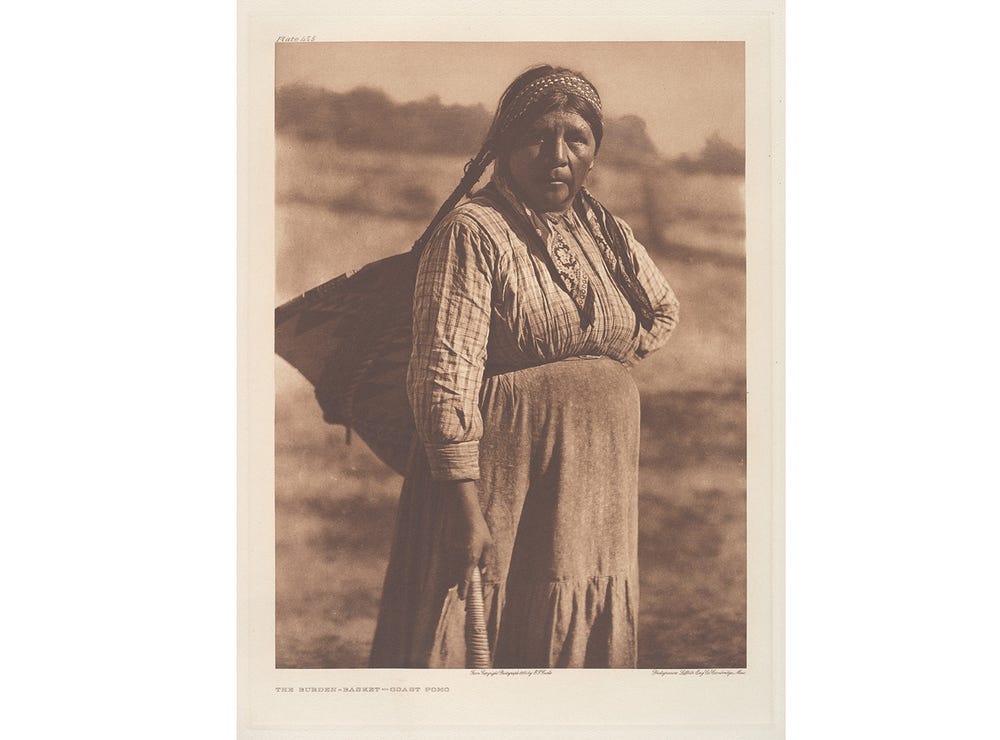

Edward Sheriff Curtis, The Burden-Basket— Coast Pomo, Plate 475, 1924. Photogravure. Rogers Fund, 1926, transferred from the Library, 1976.505.14.4. Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Once home, more specially created baskets came into use. Pomo women first separated the seeds from their dried husks, and from the stems and leaves that had fallen into the carrying basket during gathering. They accomplished this by first rubbing handfuls of the seed mixture against the inside of a large, shallow, pan-shaped basket, loosening the seeds from their husks. Women then tossed this mix into the air so that the wind helped separate the lighter chaff, which was blown away, from the heavier seed kernels that fell back into the basket. Next, they added embers to these cleaned seeds to toast them, giving the seeds a deeper, nuttier flavor. The cook skillfully kept the whole mass in constant motion, tossing it into the air and shaking the basket vigorously so that the glowing coals mixed among the seeds without scorching them or the basket.

Cecilia Joaquin from Hopland is collecting edible seeds by striking the plant with the seedbeater in her right hand and knocking the ripe seeds into the carrying basket held by its rim in her left hand. Edward Sheriff Curtis, Gathering Seeds--Coast Pomo, 1868-1952. Photographic print. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Photograph by Edward S. Curtis, courtesy of the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2002695450/

Women used stone mortars and pestles to grind the roasted seeds into a fine meal, or flour, named pinole. Sometimes this seed meal was eaten dry, often by sprinkling it over another food. Today pinole is enjoyed dusted over watermelon slices or popcorn. Other times, a little water was added to the flour, allowing it to be pressed into small, flat cakes or balls, which were then dried. Flours made from different seeds each had a distinct flavor and consistency. Cooks mixed them together, according to their own taste preferences, and might modify them further by adding salt or dried berries.

California Brome Grass, one of the native seeds/grains Pomo women harvested for eating. © 2017 Gareth Jensen, licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

Native oral traditions and archaeological studies confirm that grass and wildflower seeds were a Pomo dietary staple for many thousands of years, although their importance has been overshadowed by the emphasis placed on another primary food source, acorns. This is largely because as early as the 1830s, invasive, non-native grasses had replaced the indigenous grasses and wildflowers throughout much of the state. Thus, by the beginning of widespread white settlement of Indigenous homelands, these seeds were scarcely available for Pomo people to eat. Today, when looking at the golden grasses carpeting California’s hills, people think they see an undisturbed natural ecosystem. However, the state’s native grasslands, which once covered at least 20 million acres, have almost entirely vanished. The plants now found in its meadows and hillsides are invasive European grasses that arrived with white settlers and their livestock.

These new species are usually annuals, while the older native species were perennial bunchgrasses. What is the difference? Annual grasses only live for one year. They develop from a seed, flower, disperse their seeds, and then wither and die. Perennial bunchgrasses, however, can live for over a century. Bunchgrasses send up vegetative shoots every year from a central crown. These also flower, develop and disperse their seeds. But while most of the vegetative stems then dry up, the plant itself stays alive.

The dry outer blades of bunchgrasses often bend over to form a sort of silvery skirt that provides the plant with its own mulch and shade and gives them their characteristic tufted look. The circles of space around each “bunch” provide room for other plants to grow. This helps explain why native grasslands supported about 40 percent of the state’s total native plant species. On the other hand, invasive annual grasses carpet an area, creating an impenetrable forest of grass stems that prevents other plants from establishing themselves. Thus, as California’s native perennial grasslands have vanished, so too have many of the plant and animal species that were at home in these grasslands.

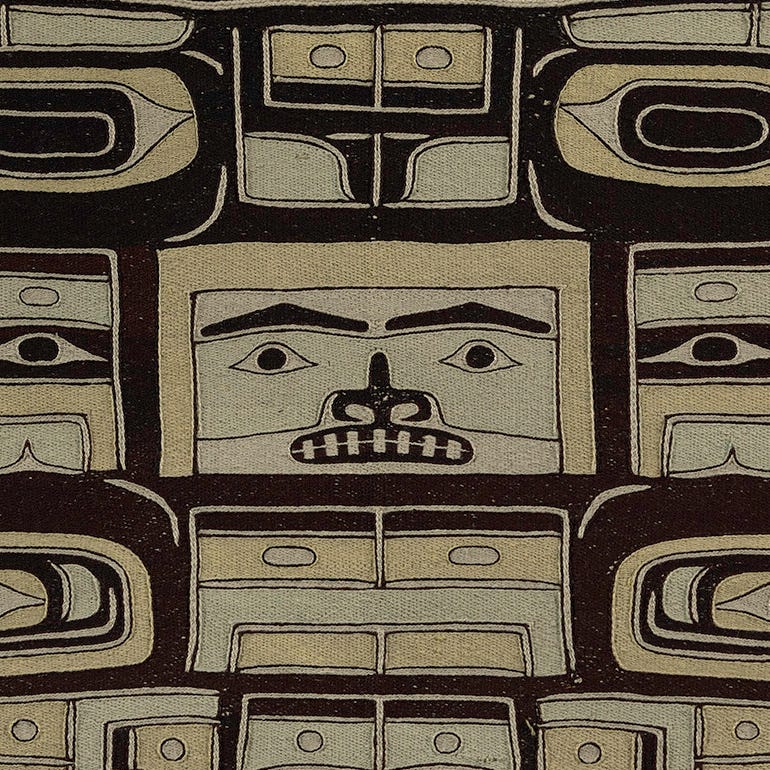

Jules Tavernier, Dance in a Subterranean Roundhouse at Clear Lake, California (detail), 1878. Oil on canvas, 48 × 72 1/4 in. (121.9 × 183.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Marguerite and Frank A. Cosgrove Jr. Fund, 2016 (2016.135). Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

I have ventured far afield, pun intended, from the initial introduction to the Pomo carrying basket. Yet, I hope that this brief examination demonstrates how enmeshed its maker was with the natural environment around her. This basket was shaped from and for this particular and abundant environment, whose beauty mirrored the rich lives of the Pomo people who called it home.

Text by Sherrie Smith-Ferri, PhD, Dry Creek Pomo / Coast Miwok Tribal Scholar.

Jules Tavernier and the Elem Pomo is on view at the de Young museum from December 18, 2021 to April 17, 2022.