Behind Truth and Beauty: Paintings Conservation

By Elise Effmann Clifford

September 13, 2018

The exhibition Truth and Beauty: The Pre-Raphaelites and the Old Masters at the Legion of Honor was created by a team that came together across the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. All four conservation departments at the de Young and Legion of Honor, including objects, paintings, works on paper, and textiles, were engaged in the preparations for this installation. Colleagues in the four departments helped shed new light on select works from the Museums’ permanent collections. In this series, our conservators share a behind-the-scenes look at the numerous preparations that took place before the exhibition opened to the public.

A lens into historic painting techniques

John Roddam Spencer Stanhope’s Love and the Maiden, featured in Truth and Beauty, offers an instructive lens into the Pre-Raphaelites’ materials and techniques as well as those of the earlier artists who inspired them. The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood originated in the late 1840s, a time of flourishing interest in the techniques and materials of the old masters.

John Roddam Spencer Stanhope, Love and the Maiden, 1877. Oil, gold paint, and gold leaf on canvas, 54 x 79 in. (137.2 x 200.7 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Museum purchase, European Art Trust Fund, Grover A. Magnin Bequest Fund and Dorothy Spreckels Munn Bequest Fund (2002.176)

The founding of the Royal Academy in 1768, while raising the status of the artist within society, also precipitated a breakdown of the apprenticeship system, in which young artists were mentored in all aspects of their craft. This, combined with the ready availability of premade artists’ materials through newly established professional art suppliers called colormen, resulted in a general loss of knowledge by artists about sound practices. Stories of disastrous cracking of paints and fading of pigments in the works of Sir Joshua Reynolds and others were well known, while the good condition of many paintings from earlier centuries was increasingly recognized.

Sir Joshua Reynolds, Anne, Viscountess Townshend, Later Marchioness Townshend (detail), 1779–1780. Oil on canvas, 95 x 58 in. (241.3 x 147.3 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Roscoe and Margaret Oakes Collection, 75.2.13. The image shows the painting during a conservation treatment with the varnish and later retouching removed. The exposed cracks in the background occurred due to the poor drying qualities of the paint.

Recent research on Pre-Raphaelite techniques shows that these artists did not attempt to faithfully reproduce earlier processes or to use only period materials. Instead, they incorporated specific lessons absorbed from their fifteenth-century predecessors to inform their approach while also benefiting from materials newly available to nineteenth-century artists. Some of what they responded to was stylistic, such as meticulous attention to detail and a preference for compositions that do not direct focus on one area over another. But the most important technical similarity was the use of thin transparent or translucent paint over a white ground. They also diverged from the old masters in their preference for canvas rather than wood panel as a support, and in their eager adoption of newly synthesized pigments.

Left: John Everett Millais, Mariana, 1851. Oil on panel, 23 1/2 x 19 1/2 in. (59.7 x 49.5 cm). Tate, London, Accepted by HM Government in lieu of tax and allocated to the Tate Gallery (1999, T07553). © Tate, London 2018; Right: Jan van Eyck, The Annunciation, ca. 1434/1436. Oil on canvas transferred from panel, 35 1/2 x 13 3/8 in. (90.2 x 34.1 cm). National Gallery of Art, Washington DC, Andrew W. Mellon Collection, 1937.1

Love and the Maiden reflects the craft and optical concerns of early Italian painting while remaining very much grounded in nineteenth-century artistic materials and practice. The painting is Stanhope’s response to the early Italian egg tempera and fresco paintings that he saw on his sojourns to Italy, as well as those newly purchased by the National Gallery in London. Early Italian paintings were traditionally on poplar wood panels prepared with gesso and then painted with pigments bound in egg yolk (tempera), or on walls prepared with plaster and painted with pigments ground in water (fresco). Although similar in appearance, Love and the Maiden does not conform to either of these constructions, and close examination reveals that Stanhope’s process was more complex than has generally been portrayed in studies of the artist.

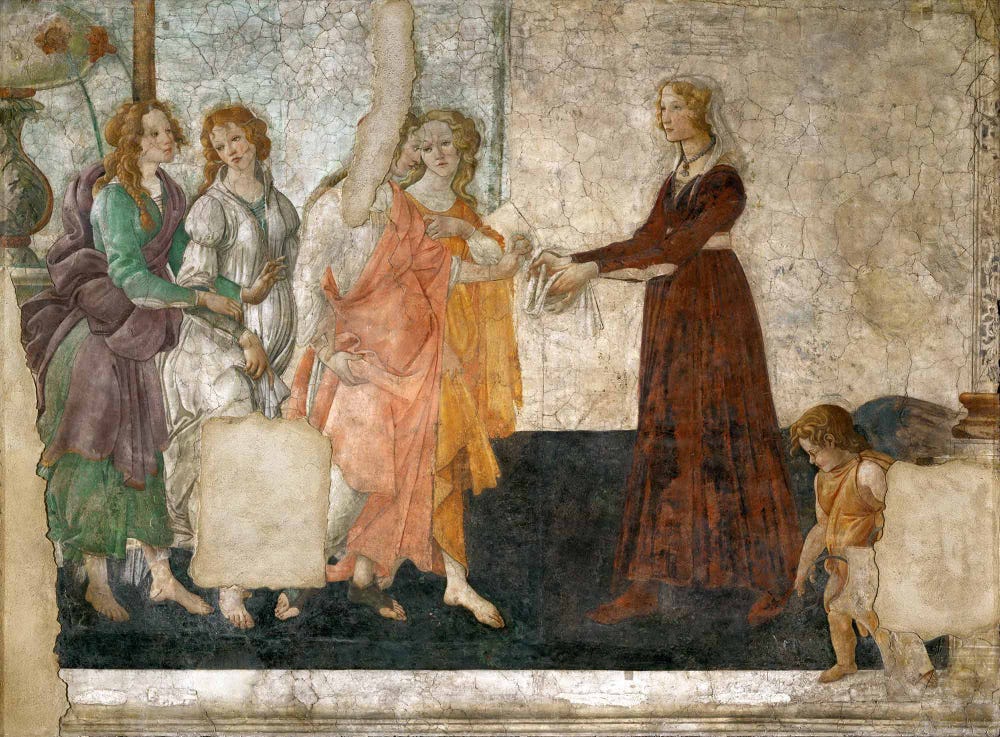

Sandro Botticelli, Venus and the Three Graces Offering Gifts to a Young Lady (detail), ca. 1483. Fresco. Musée du Louvre, Paris. An example of the type of painting that influenced Stanhope in his mature years.

Unlike the traditional Italian tempera process, in which forms were carefully modeled with individual brushstrokes, or fresco, in which color is applied directly to fresh plaster, Stanhope built up his composition in many layers. He first drew with fluid brown paint, then sculpturally undermodeled with thick white paint, and finally painted each compositional element in color.

Detail of Love and the Maiden showing white brushmarks of the textural underlayer and a round unpainted flower with the brown drawing still visible.

Stanhope used this technique to achieve a variety of effects in Love and the Maiden: the smooth but pitted surface of some flesh areas, recalling the plaster of a fresco; the brushed texture of the Maiden’s drapery; and the highly detailed flora in relief in the foreground.

Love and the Maiden detail in raking light showing texture created by the thick white underpaint.

Stanhope was regarded as “the pioneer” in the British Tempera Revival later in the century, and his Love and the Maiden, since its sale at auction in 1997, has been assumed to be an important example of Stanhope’s mastery of this medium due to the light tone and low saturation of the colors. However, recent analysis did not detect any egg protein in the paint — only oil. Although a simplified narrative of Stanhope’s development — one in which he broke from painting in oil in favor of tempera as his work became more influenced by Italian art — is tempting, the artist in fact achieved the effects that he desired, as least in some part, with the continued use of oil during the later years of his career.

Text by Elise Effmann Clifford, head of Paintings Conservation.

Further reading

Billinge, Rachel, et al., “Methods and Material of Northern European Painting in the National Gallery, 1400–1550,” National Gallery Technical Bulletin 18 (1997): 6–55.

Bomford, David, Jill Dunkerton, Dillian Gordon, Ashok Roy, and Jo Kirby, Art in the Making: Italian Painting before 1400 (London: National Gallery 1992).

Clifford, Elise Effmann, “John Roddam Spencer Stanhope and the Lessons Learned from the Masters,” in Truth and Beauty: The Pre-Raphaelites and the Old Masters, exh. cat. (San Francisco: The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 2018), 251–259.

Stanhope, John Roddam Spencer, “Yolk of Egg Tempera,” Papers of the Society of Painters in Tempera: vol. 1, 1901–1907, 2nd ed. Edited by Mary Sargant-Florence (Brighton, UK: Dolphin Press 1928), 28. Originally written for the Society of Painters in Tempera, April 23, 1903.

Stirling, A. M. W., “The Life of Roddam Spencer Stanhope, Pre-Raphaelite, a Painter of Dreams,” in A Painter of Dreams and Other Biographical Studies (London: John Lane, 1916).

Talley, M. Kirby, Jr., “All Good Pictures Crack: Sir Joshua Reynolds’s Practice and Studio,” in Reynolds, exh. cat. (London: Royal Academy of Arts, 1986), 55–70.

Joyce Townsend, Jacqueline Ridge, and Stephen Hackney, Pre-Raphaelite Painting Techniques (London: Tate, 2004).