de Young Organizes Large-Scale, Traveling Survey of Precisionism

Jan 30, 2018

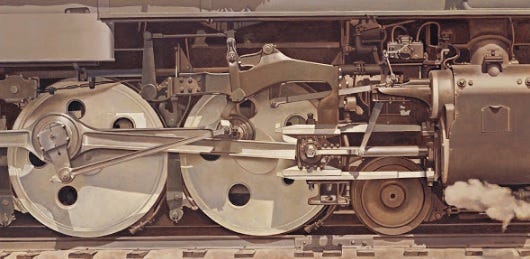

Charles Sheeler, Rolling Power, 1939. Oil on canvas, 15 x 30 in. The Smith College Museum of Art, SC, 1940:18.

de Young \ March 24–August 12, 2018

SAN FRANCISCO—The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco (FAMSF) are proud to premiere Cult of the Machine: Precisionism and American Art, the first large-scale exhibition in over 20 years to survey this characteristically American style of early twentieth-century Modernism. Organized by FAMSF and on view at the de Young, the exhibition addresses the aesthetic and intellectual concerns that fueled the development of this artistic style during the 1920s and 1930s. More than 100 Precisionist masterworks by seminal artists such as Charles Sheeler, Georgia O’Keeffe, and Charles Demuth are displayed alongside prints by photographers such as Imogen Cunningham and Paul Strand; clips from films such as Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times; and extraordinary decorative arts and industrial objects from the period—including a vintage Cord Phaeton automobile—to reflect the widespread embrace of a machine-age aesthetic by artists, designers, and the public alike. Cult of the Machine considers how the style reflects the economic and social changes wrought by industrialization and technological progress during the Machine Age in America. Visitors are encouraged to draw connections to our own technological moment, one in which optimism and dreams about what technological progress can achieve are tempered with anxiety or suspicion about its potential dangers and misuses.

“This project will resonate here in the heart of the Bay Area, at the epicenter of the emerging tech industries of Silicon Valley,” says Max Hollein, Director and CEO of the Fine Arts Museums. “We, like our visitors, often reflect on how our daily lives are impacted by new technologies—much as the Precisionists did almost a century ago. Aesthetically, these works are masterpieces, but perhaps they represent something more. Like all great works of art, they transcend their historical moment and give us insights about both our present and our future.”

The majority of Precisionist works were created during the tumultuous period between the World Wars, decades when the country’s new technologies and industries were met with multiple and contradictory responses in the arts, literature, and popular culture. As today, there was a general excitement in the United States about technology’s capacity to engender opportunity and improve the conditions of daily life, yet these attitudes coexisted with fears that it would supplant human labor and deaden the natural rhythms of life. Precisionist artists reflected such contradictions and complexities in their work, capturing a sense of the beauty and the coldness, the sublimity and the strangeness of the mechanistic societies in which they lived.

“The responses to industrialization in these works are particularly fascinating and relevant to contemporary audiences who find themselves in the midst of a fourth industrial revolution,” says Emma Acker, associate curator of American art for the Fine Arts Museums. “They hold up a mirror to our own complicated responses to the legacies of industrialization and technological progress as we continue to navigate our relationships with the ever-multiplying devices that surround us and shape our daily existence.”

Precisionism emerged in America in the teens and flourished during the 1920s and 1930s. The style combined realist imagery with abstracted forms and married the influence of avant-garde European art styles such as Purism, Cubism, and Futurism with American subject matter. Artists associated with the style typically produced highly structured, geometric compositions with smooth surfaces and lucid forms to create a streamlined, “machined” aesthetic, with themes ranging from the urban and industrial to the pastoral.

Masterpieces of machine age Modernism are on loan from more than 50 institutions from across the United States, including the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Brooklyn Museum of Art, Dallas Museum of Art, Harvard Art Museums, National Gallery of Art, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Walker Art Center and many others.

Cult of the Machine is curated by Emma Acker, associate curator of American Art for the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. It is on view at de Young from March 24 through August 12, 2018. The exhibition will then travel to the Dallas Museum of Art, where it will be on view from September 9, 2018, through January 6, 2019.

In Detail

Visitors enter the exhibition through an immersive film environment, which conveys a sense of the repetitive monotony of the assembly line.

The exhibition begins with objects by New York Dada artists Marcel Duchamp and Francis Picabia that reveal the influence of their “machine aesthetic” on the development of Precisionist works—including Morton Livingston Schamberg’s 1916 suite of Mechanical Abstractions. These abstracted renderings of modern machines are paired with a screening of Ralph Steiner’s 1930 film Mechanical Principles, a meditation on various mechanisms in almost balletic motion. Gerald Murphy’s monumental, immaculately rendered painting Watch (1925)—whose composition may encode veiled personal meanings, merging man and mechanism—is a centerpiece of the gallery.

The next gallery focuses on images of industrial landscapes, including paintings by Sheeler modeled on documentary photographs he was commissioned to take of Ford Motor Company’s River Rouge plant. The smooth, streamlined aesthetic of such works—in which traces of the artists’ brushwork are often barely visible—can be seen as a response not only to the sleek forms and polished surfaces of the machine, but also to the new methods of industrial production in the early to mid twentieth century, championed by Henry Ford, that emphasized automated and “de-skilled” labor. Nearby, Sheeler’s Upper Deck (1929) is displayed alongside the photograph on which it is based, highlighting the ways in which the artist worked across media. The gallery also features a group of landscapes by Demuth based on industrial scenes in and near his hometown of Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

Iconic design objects, including a 1937 Cord 812 Phaeton automobile, that reflect the widespread embrace of a streamlined Machine Age aesthetic by artists, designers, and the public alike are displayed in the next gallery. In addition, this installation incorporates machine parts from the period that were displayed in the radical 1934 Machine Art exhibition hosted by the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

The gallery that follows features masterpieces from Sheeler’s Power series, commissioned by Fortune magazine in 1938, such as his Rolling Power (1939), as well as Ralston Crawford’s Overseas Highway (1939) and Elsie Driggs’s Aeroplane (1928). These works—which have traditionally been viewed as celebratory responses to industrialization and technological progress—are grouped with others that seem to convey a more ambivalent view of such innovations. The range and at times the ambiguity of Precisionist perspectives on modernization provide a compelling aspect of the work, and reflect the mixed emotions Americans expressed during the Machine Age towards technological innovation.

A gallery dedicated to Social Realist perspectives on American life during the 1920s and 1930s illustrates aspects of American life that are left “out of the frame” in the typically de-populated, highly aesthetic views of industry characteristic of Precisionism. These works shed light on the labor strikes, protests, and mass unemployment that affected the lives of millions of American during this period. The gallery features a wall-size projection of clips from Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times (1936) and a juxtaposition of newspaper headlines from our current era and the Machine Age that highlights the anxieties about technological unemployment that existed then as now.

The next gallery features Precisionist views of the urban landscapes of the early twentieth century, replete with soaring skyscrapers and bridges, elevated train and subway tracks, and industrial waterways. This gallery also includes a screening of Sheeler and Strand’s short film Manhatta (1920), which showcases the early twentieth-century city as its subject. The vertiginous bird’s-eye perspectives of many of the compositions in this gallery capture the dramatic scale of the buildings, which dominate the landscape both physically and metaphorically, towering over their human counterparts. Decorative arts objects that were inspired by the vertical forms of the modern skyscraper are also on display.

Rural landscapes, which were created amid the Colonial Revival movement, which was in full swing in 1920s and 1930s America and is reflected in works such as Sheeler’s Kitchen, Williamsburg (1937) are explored next. These examples point to the Precisionists’ impulse to focus on specifically American subjects, celebrating the nation’s innovations and cultural heritage, and asserting its artistic independence from Europe. Precisionist artists’ frequent representations of American rural landscapes, regional architecture, and traditional handicrafts may telegraph anxieties about the potentially dehumanizing effects of industrialization and nostalgia for a simpler way of life—concerns that were widespread at the time.

The last gallery of the exhibition showcases Clarence Carter’s War Bride (1940), which conveys the darker aspects of humanity’s relationship to technology. This final section includes an interactive feature that encourages visitors to consider more generally the relationship between humans and machines in our own era—including the ways in which we relate to, benefit from, resist, and learn to live with technology.

deyoungmuseum.org \ #CultoftheMachine \ @deyoungmuseum

Visiting \ de Young

Golden Gate Park, 50 Hagiwara Tea Garden Drive, San Francisco.

Open 9:30 a.m.–5:15 p.m. Tuesdays–Sundays. Open select holidays; closed most Mondays.

Tickets

For adults, tickets are $28. Discounts for students, youth and seniors are available. Members and children five and under receive free admission. More information regarding tickets can be found at deyoungmuseum.org.

Digital Story

How does innovation redefine humanity? Immerse yourself in the efficiently, process, and technology of the Machine Age and discover the surprising connections between past and present. dystories.org/machine

Exhibition Catalogue

Essays explore the origins of the style—which reconciled realism with abstraction and adapted European art movements like Purism, Cubism, and Futurism to American subject matter—as well as its relationship to photography, and the ways in which it reflected the economic and social changes brought about by industrialization and technology in the post–World War I world. In addition to making a meaningful contribution to the resurging interest in Modernism and its revisionist narratives, this book offers copious connections between the past and our present day, poised on the verge of a fourth industrial revolution. Published in association with Yale University Press. Hardcover, 244 pages. Available for purchase here.

Audio Tour

Exhibition curator Emma Acker and local innovators explore the excitement and tensions surrounding industrialization and technology in the early twentieth century and today. Order with your exhibition tickets (Android or iOS) or rent a player at the museum.

Exhibition Organization

This exhibition is organized by the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. Presenting Sponsors: Art Mentor Foundation Lucerne; William K. Bowes, Jr. Foundation; Clare C. McEvoy Charitable Remainder Unitrust and Jay D. McEvoy Trust. President’s Circle: The Michael Taylor Trust. Curator’s Circle: The Herbst Foundation, Inc.; Ray and Dagmar Dolby Family Fund; San Francisco Auxiliary of the Fine Arts Museums. Patron’s Circle: George and Marie Hecksher, and Burt and Deedee McMurtry. Additional support is provided by Mr. and Mrs. Charles Crocker, Maurice W. Gregg, and Dorothy Saxe. This project is supported in part by an award from the National Endowment for the Arts.

About the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, comprising the de Young in Golden Gate Park and the Legion of Honor in Lincoln Park, are the largest public arts institution in San Francisco.

The de Young originated from the 1894 California Midwinter International Exposition in Golden Gate Park and was established as the Memorial Museum in 1895. It was later renamed in honor of Michael H. de Young, who spearheaded its creation. The present copper-clad landmark building, designed by Herzog & de Meuron, opened in October 2005. It holds the institution’s significant collections of American painting, sculpture, and decorative arts from the 17th to the 21st centuries; art from Africa, Oceania, and the Americas; costume and textile arts; and international modern and contemporary art.

Media Contact

Miriam Newcomer, Director of Public Relations \ mnewcomer@famsf.org \ 415.750.3554