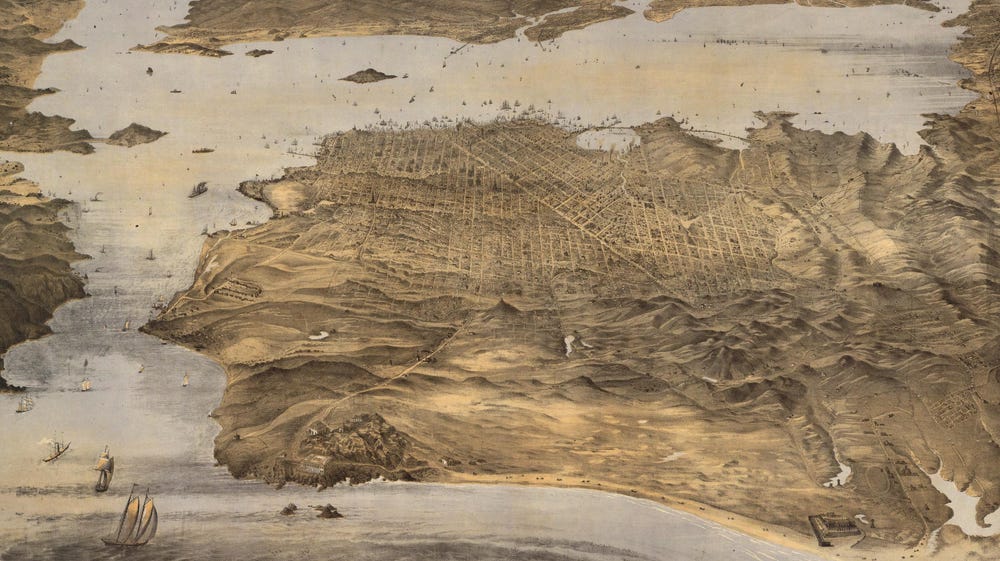

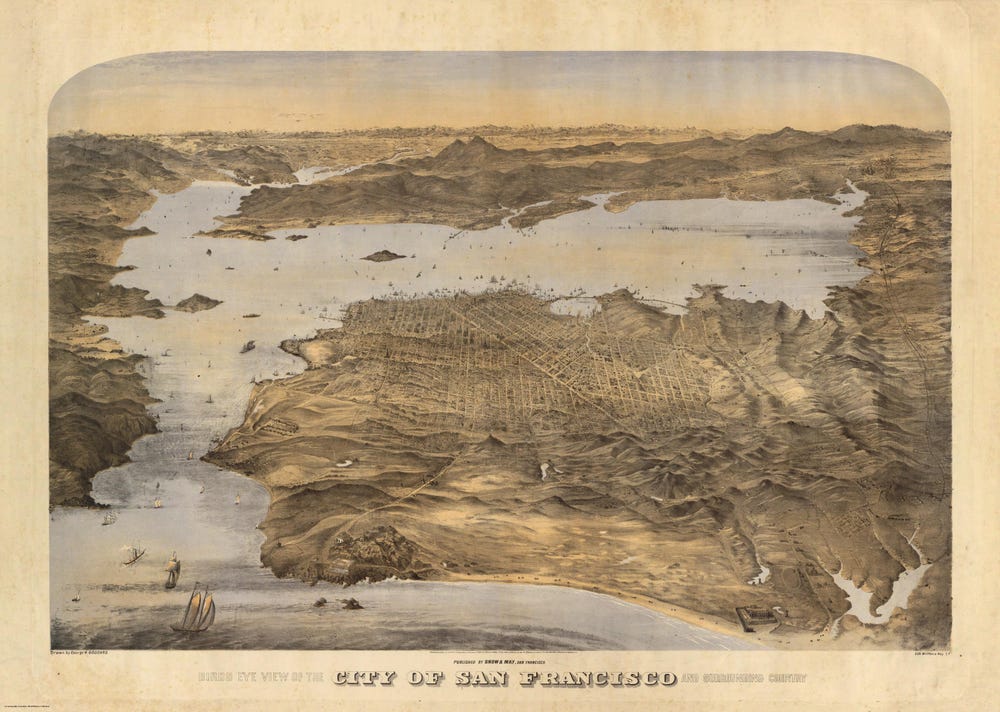

Bird’s-eye view of San Francisco by George Goddard (detail), 1868. Image: David Rumsey Map collection

Lincoln Park history

The California Palace of the Legion of Honor was founded on November 11, 1924, in San Francisco’s Lincoln Park. During the 19th century, before the museum or park existed, the land operated as City Cemetery. It is estimated that between 10,000 and 19,700 burials remain within the grounds of Lincoln Park today. In 2022, City Cemetery was established as a landmark.

Ramaytush Ohlone

The San Francisco Bay Area is on the unceded territory of the Ramaytush Ohlone. An independent Ohlone tribe called Yelamu were the original peoples who lived within San Francisco, inhabiting the peninsula from at least AD 500 to 1780. They lived in five inland villages: Chutchui, Sitlintac, Amuctac, Tubsinte, and Petlenuc. The closest village to present-day Land’s End and Lincoln Park was Petlenuc, at the tip of the peninsula, near the Presidio and Crissy Field. Historians believe the Ohlone did not live at Land’s End, but came to the area to hunt sea mammals and gather shellfish, plants, and bird eggs.

Ohlone in a Tule Boat in the San Francisco Bay 1822, by Louis Choris

Outside Lands

The earliest-known colonial use of the hills above Land’s End is recorded by Charles Caldwell Dobie in his 1933 book San Francisco A Pageant. Dobie notes that Don Juan de Rivera, the comandante of California, was tasked with exploring the port area for settlement potential. A cross was planted where the Legion now stands in 1774 by Fray Francisco Palou, the priest who accompanied de Rivera. The cross became the meeting point for future expeditions and surveys.

Land’s End can be seen in the front of this bird’s-eye view of San Francisco by George Goddard, 1868. Image: David Rumsey Map collection

When Spanish colonizers established San Francisco in 1776, the area was so remote and difficult to access that it was dubbed “Outside Lands.” After California was ceded to the United States at the end of the Mexican-American War in 1848, the only visitors to this area were naturalists who braved the journey to observe marine mammals. The land was purchased in 1849 by Sweeny & Baugh, the firm who built a telegraph station on what’s now Telegraph Hill. They built a second station at Land’s End in 1851.

In 1863, construction began on the Cliff House and Point Lobos Avenue, which connected Outside Lands to downtown San Francisco. The land remained largely unincorporated until an 1866 act of Congress granted the area to San Francisco. This allowed for the creation of Golden Gate Park, as well as a new municipal cemetery.

City Cemetery

In 1868, the City Board of Supervisors designated approximately 200 acres near Land’s End as a municipal cemetery. The cemetery extended west from 33rd Avenue to 48th Avenue and north from Clement Street toward a bluff overlooking the ocean. From 1870 to 1876, the cemetery accepted relocated remains from Yerba Buena Cemetery (which had been closed in 1854 to accommodate the new City Hall in what is now Civic Center), as well as indigent individuals who died without the means to pay for burial elsewhere.

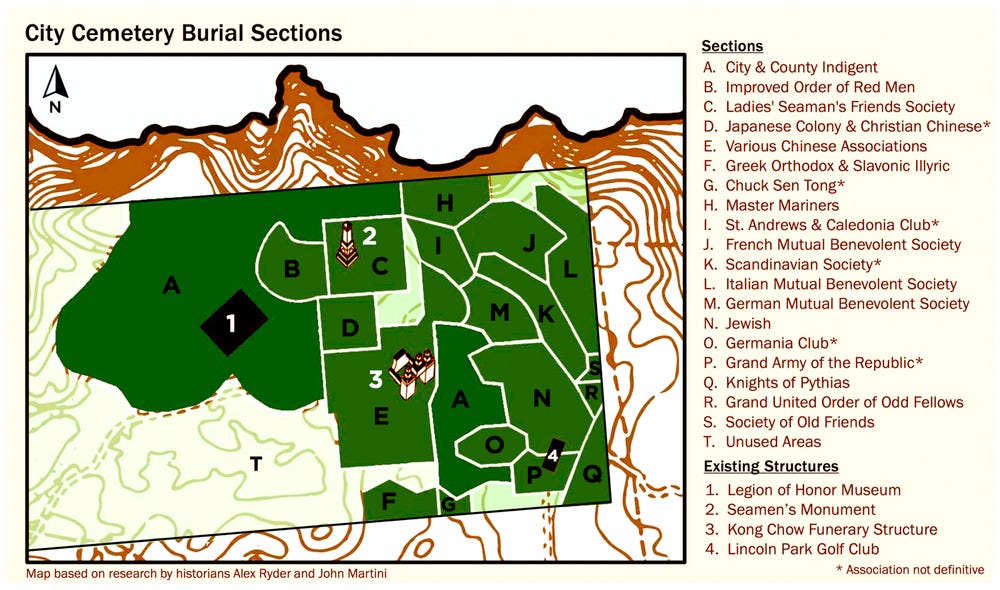

Map of City Cemetery based on research by historians Alex Ryder and John Martini

In the late 1870s, the Board of Supervisors began to grant blocks within City Cemetery to local benevolent, social, and religious societies. City Cemetery thus functioned as a “social safety net” for members of these groups at a time when social welfare was nonexistent. City Cemetery stood alone in this function, as after 1870, it was the only municipal burial place for socioeconomically marginalized people. Other cemeteries in San Francisco, like those surrounding Lone Mountain, were privately owned.

The municipal section of City Cemetery that opened in 1870 was full by 1882. By that time, the section was surrounded by membership organizations. So in October 1882, the city identified a section farther northwest on top of a hill for a second municipal section. This would later become the site of the Legion of Honor.

Looking northwest at City Cemetery from Geary Boulevard and 32nd Avenue in 1900. The area labeled “City Section” at the top left is where the Legion of Honor would be built 20 years later

In the 1880s and 1890s, city leaders, neighborhood booster groups, and residents began advocating for the closure and removal of burial grounds within San Francisco. In 1887, a resolution was introduced to convert City Cemetery into a park.

Lincoln Park

San Francisco banned new burials at City Cemetery in 1898. Two years later, interment within all cemeteries in the city was outlawed. In December 1908, the city required all bodies to be moved. However they did not provide financial support to carry out the requirement. While the four cemeteries at Lone Mountain could afford the cost of relocation, the associations at City Cemetery could not, and some challenged the decision. In July 1909, the Italian Benevolent Society objected to the city’s plan. In response, the Board of Supervisors promised that if they did indeed turn the cemetery into a park, they would remove the society’s bodies at the city’s expense. There is no proof the city carried out this promise. Some disinterments were removed on an ad hoc basis, but records show that only a few hundred remains were removed before City Cemetery was converted into a park and golf course.

More than 29,000 people were buried in City Cemetery between 1870 and 1898. Of these, more than 6,300 were Chinese individuals whose bones were later disinterred, in accordance with their death rites, and transported to China. The extent to which other societies and organizations removed their dead is unclear. The government made no attempt to remove the remains of indigents in their sections, including those at the location of the Legion of Honor. It is estimated that between 10,000 and 19,700 burials remain in the park today.

Although burials remained, aboveground markers of City Cemetery were almost completely removed by 1921. Any burial records from the cemetery were likely lost in the 1906 earthquake and fire. Grave markers, monuments, caretaker buildings, section fencing, water tanks, and other cemetery infrastructure were demolished or relocated during the creation of the Lincoln Park Golf Course. Two notable exceptions remain today: the Kong Chow funerary structure and the Ladies’ Seaman’s Friend Society monument.

Attributed to Gabriel Moulin, No. 53: Front Elevation, Showing all Forms Stripped Off Concrete Walls, 1923. Legion of Honor Construction Album, Archival photograph, 3 x 5 in. (7.6 x 15.2 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco Archives

When the city granted the land to Adolph B. and Alma de Bretteville Spreckels to build the Legion of Honor in September 1920, City Cemetery was all but lost to history. There is no record that when construction broke ground in 1921 the city notified anyone of the possible presence of human burials. A December 1921 article in The Daily News described how the original construction crew of the museum dealt with burials, noting, “No provision was made for the reburying of the bodies.” Crews were not informed that the cemetery had never been moved and were unprepared to deal with the remains. There were no procedures for moving human remains, so they simply pushed them out of the way and continued their work. The original crew’s actions were corroborated by the discovery of pits of remains, as well as pipes and building structures running through burials, during a 1993–1994 excavation of the grounds.

On November 11, 1924, the California Palace of the Legion of Honor opened to the public, 26 years after burials at City Cemetery were banned and 13 years after Lincoln Park opened. Over the next 70 years, City Cemetery was largely forgotten. Nonetheless, human remains and funerary items were periodically discovered. As part of a renovation and expansion of the Legion in the early 1990s, 740 coffin burials were encountered and removed. A section of the French section was uncovered by a local historian in 2018. A 2019 city drainage project on El Camino Del Mar also revealed human remains. The Legion represents the only major construction projects done in Lincoln Park. Lincoln Park Golf Course has not excavated much of its grounds below surface level, but there is believed to be a similar density of burials throughout the park.

Landmark status

In 2022, San Francisco designated City Cemetery as a landmark. On October 4, 2022, the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association held a ceremony at the King Chow funerary structure to commemorate the designation. They plan to hold annual ceremonies each fall. We join the city in recognizing and commemorating City Cemetery.

The Cheung Yeung ceremony at the Kong Chow funerary structure on October 4, 2022. Image courtesy of SF Heritage