While fans were a staple of the eighteenth-century woman’s wardrobe, visitors to the exhibition Fans of the Eighteenth Century at the de Young may be surprised to learn that these accessories were also useful social tools.

Thomas Frye, Portrait of a Lady, 1761. Mezzotint. Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, California State Library long loan

Women used fans as extensions of their body language to non-verbally express a range of emotions. Affluent young women even learned the correct way to manipulate a fan as part of good manners. As a writer for the English daily, The Spectator, observed (albeit, satirically) on June 27, 1711, “There is an infinite Variety of Motions to be made use of in the Flutter of a Fan”:

There is the angry Flutter, the modest Flutter, the timorous Flutter, the confused Flutter, the merry Flutter, and the amorous Flutter. Not to be tedious, there is scarce any Emotion in the Mind that does not produce a suitable Agitation in the Fan; insomuch, that if I only see the Fan of a disciplin'd Lady, I know very well whether she laughs, frowns, or blushes. I have seen a Fan so very angry, that it would have been dangerous for the absent Lover that provoked it to have come within the Wind of it; and at other times so very languishing, that I have been glad for the Lady's sake the Lover was at a sufficient Distance from it. I need not add, that a Fan is either a Prude or Coquet according to the Nature of the Person that bears it.

Fans were also used by women to capture the gaze, typically of men. Giacomo Casanova (1725–1798), the Italian adventurer, philanderer, and subject of the special exhibition Casanova: The Seduction of Europe at the Legion of Honor, recounts his female contemporaries signaling, gesturing, beckoning, and, in one instance, striking him with their fans to attract his attention, in his colorful twelve-volume autobiography, A History of My Life. As The Spectator also cautioned (and Casanova experienced), “Women are armed with Fans as Men with Swords, and sometimes do more Execution with them.”

Excerpt from the English daily The Spectator, no. 102, June, 27, 1711 via Google Books

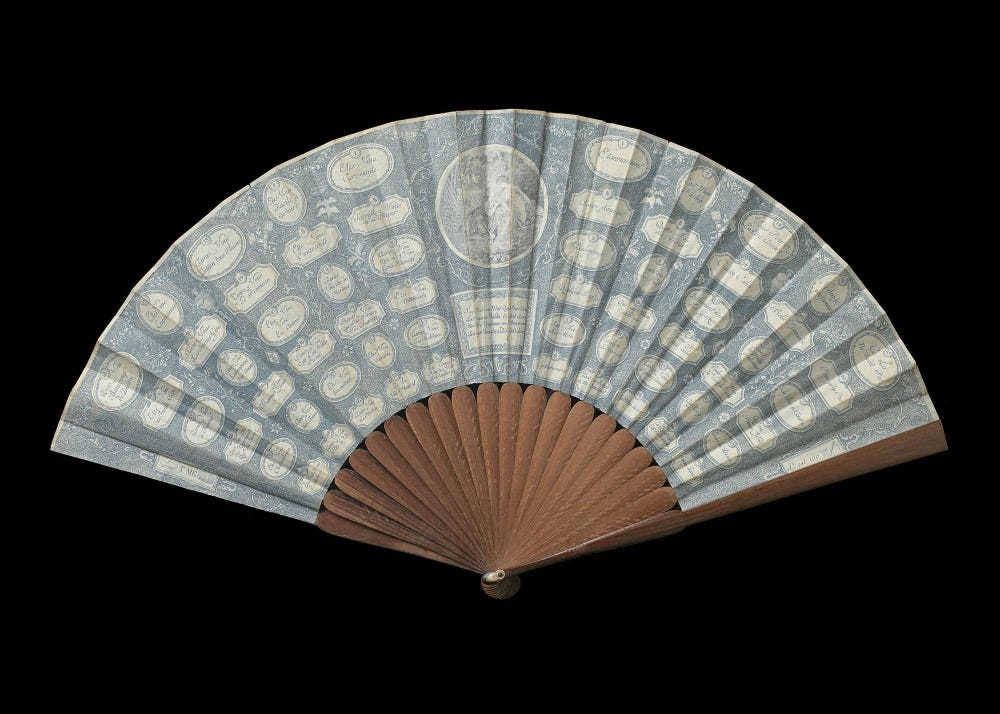

Various sources mention users wielding their fans in accordance with coded “languages,” in which fans were positioned in different ways to spell out individual letters, form words, and convey surreptitious emotions and desires. While it is unclear to what extent these languages were actually used – spelling out individual letters, for example, would have been quite cumbersome – some enterprising fan makers did interpret them into aid-to-memory “Conversation Fans” (whose designs were formed by directions for spelling words) and romantic question and answer games.

“Amorous question and answer game” fan, ca. 1795. France. Leaf of paper with dotted engraving in color; sticks and guards of wood and bone. Royal Antiquarian Society, Felix Tal Fan Collection

Further Reading

- Alexander, Hélène. Fans. London: B. T. Batsford, 1984.

- Armstrong, Nancy. A Collector’s History of Fans. New York: Clarkson N. Potter Inc., 1974.

- Armstrong, Nancy. Fans in Spain. London: Philip Wilson Publishers, 2004.

- Bennett, Anna Gray, with Ruth Berson. Fans in Fashion: Selections from the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. San Francisco: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco; Rutland: C.E. Tuttle, 1981.

- Casanova, Giacomo. History of My Life. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2006.

- Commoner, Lucy. Folding Fans in the Collection of the Cooper-Hewitt Museum. New York: Smithsonian Institution, 1986.

- Steele, Valerie. The Fan: Fashion and Femininity Unfolded. New York: Rizzoli, 2002.

Written by Laura L. Camerlengo, associate curator of costume and textile arts.