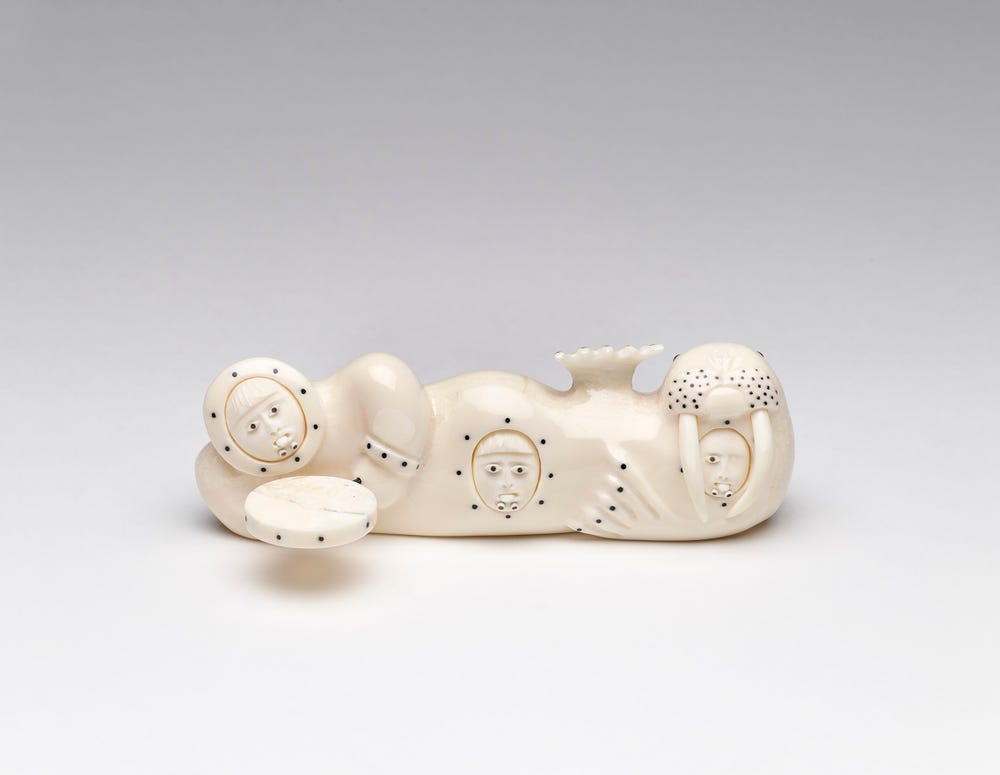

Cover artwork of Yua, Spirit of the Arctic: Levi Tetpon, Drummer, walrus, three faces, 1995. Walrus tusk, whale baleen, wood, and paint, 2 x 6 1/4 x 2 3/8 in. Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Bequest of Thomas G. Fowler, 2007.21.273

In recognition of Indigenous Peoples’ Day, celebrated this year on Monday, October 12, we would like to share excerpts from a recent publication from the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco celebrating Native artists from the Far North: Yua, Spirit of the Arctic: Highlights from the Thomas G. Fowler Collection. The works in the collection were made by diverse artists separated by great distances and time who are nonetheless united by the concept of yua (Yup’ik) or inua (Iñupiaq), a recognition that all things, including objects, have a unique inner essence or spirit.

The artworks, be they utilitarian, decorative, or ceremonial, highlight the raw materials used to make them — walrus tusk, whalebone, driftwood, stone — evoking the Arctic environment and exhibiting an exquisite appreciation of form and design. This new publication combines art historical and anthropological essays with lively, personal accounts from artists and scholars, exploring the connection between humans and the environment, the interwoven nature of the spiritual and the quotidian, and the aesthetics of Arctic life.

Included here are excerpts from statements made by contemporary artists Abraham Anghik Ruben and David Ruben Piqtoukun about their works in the collection.

David Ruben Piqtoukun, Bear in Shamanic Transformation, ca. 1991. Steatite, bone, aluminum, and pigment, 20 3/4 × 14 1/4 × 8 1/2 in. (52.7 × 36.2 × 21.6 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Bequest of Thomas G. Fowler, 2007.21.269

David Ruben Piqtoukun (Canadian, Inuit, b. 1950), Bear in Shamanic Transformation, ca. 1991

I was registered as being born on May 10, 1950. My parents, Billy and Bertha Ruben, told me that my birthplace was Argo Bay, just west of Paulatuk. I have seventeen siblings in our original family grouping. My beautiful parents and a few siblings have since died. I still have eight brothers and four sisters. A number of us in my age group (ages four to six years old) were boarded onto a plane and carted off to a place called Aklavik to attend boarding school. We were all dressed in traditional clothing — caribou or sealskin parkas and pants — and wearing mukluks to cover our feet. We were abducted, in essence. This is the story of our abduction to attend a schooling system that I call “an education in forgetting.” The rules were very straightforward for every Inuit or Indian: do not speak your language or even whisper your original language to yourself or to anyone else around you. You will all be dressed to look alike in pants and a shirt or sweater, and you will wear shoes (whether they fit or not). The final rules of residential school were to always obey the nuns, keep your snotty nose clean, no fighting, and never speak your Eskimo language!

My recollection was that I retaliated at every turn. My deepest resentment was toward being surrounded by all the religious statues and forced religious prayers and eating unknown food and not having a clue about my parents or whereabouts. I was your classic lost child. That is my recollection of the last years of my early life.

Through stone carving I am getting an education in remembering. I have continued to travel to various parts of the High Arctic but especially to my hometown, Paulatuk. I will always collect stories and learn more about shamanism and Inuit mythology. That is the source of my motivation and creative endeavors. That is the source of my fascination and inspiration.

David Ruben Piqtoukun, Bear in Shamanic Transformation, ca. 1991. Steatite, bone, aluminum, and pigment, 20 3/4 × 14 1/4 × 8 1/2 in. (52.7 × 36.2 × 21.6 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Bequest of Thomas G. Fowler, 2007.21.269

I completed this stone sculpture at a time when my personal life was collapsing. Creating this work was my only lifeline to maintaining my sanity. The Bear-Man in our Inuit mythology is symbolic of the spiritual and physical power that humans lack in times of personal weakness. I needed to create this sculpture and understand its true meaning. The Bear-Man has been summoned by Elders of a remote village in the High Arctic. People have been stricken by illness, disease, and famine. The shaman’s responsibility is to find the source and origin of this dilemma. The Bear-Man is one of the most powerful shamans in Inuit existence and is capable of tackling impossible feats. Within a short period of time, the shaman finds the cause of the problems the people are facing. A number of taboos have occurred or have been broken by the villagers. Life is restored, and all the living resources for their survival return. In my case, I allowed my ego to consume my existence.

That is the cause of my broken taboo! We all have spirit helpers to assist us in our troubled periods of life. Do not be afraid to ask for help! It is vitally important to understand what or who is your spirit helper!

— David Ruben Piqtoukun

David Ruben Piqtoukun is an Inuvialuit artist who works primarily in stone, antler, bone, and metal. His work has been featured in solo and group exhibitions in the United States and in Canada and has been collected by museums in North America and Europe.

Abraham Anghik Ruben, Passage of Spirits, before 2004. Stone, musk ox horn, antler, wood, and thread, 27 3/4 × 40 1/2 × 13 in. (70.5 × 102.9 × 33 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Bequest of Thomas G. Fowler, 2007.21.292.a–y

Abraham Anghik Ruben (Canadian, Inuvialuit, b. 1951), Passage of Spirits, before 2004

This sculpture represents the passing of the way of life among western Arctic Inuvialuit during the second half of the 1890s. With the arrival of commercial whaling and exploration in the Beaufort Sea, the traditional way of life was forever changed. Along with material changes to the culture, the Inuvialuit spiritual beliefs were also affected. The boat represents the passage of the old beliefs. The oarsmen are men, animals, birds, and spirits. Beneath the boat, Sedna and her sea mammals carry her boat into the setting sun. The spirals hovering above the boat are made of antler and represent the northern lights, showing the way to their ancestors.

Abraham Anghik Ruben, Passage of Spirits (details), before 2004. Stone, musk ox horn, antler, wood, and thread, 27 3/4 × 40 1/2 × 13 in. (70.5 × 102.9 × 33 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Bequest of Thomas G. Fowler 2007.21.292.a–y

— Abraham Anghik Ruben

Abraham Anghik Ruben is an Inuvialuit artist of international renown. His work focuses on arts and cultural traditions of Inuit culture, Norse myths and legends, and historical contact.

You can directly support the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco when you purchase Yua, Spirit of the Arctic (members save 10 percent) from the Museum Stores at shop.famsf.org.

Watch a Curator Conversation

The video features Christina Hellmich, curator in charge of the arts of Africa, Oceania and the Americas and the Jolika Collection of New Guinea Art; Hillary C. Olcott, associate curator of the arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas; and Chuna McIntyre, Central Yup’ik artist, cultural consultant, and contributing author to Yua, Spirit of the Arctic.

Learn more about the arts of the Americas at the de Young.

Cover artwork of Yua, Spirit of the Arctic: Levi Tetpon, Drummer, walrus, three faces, 1995. Walrus tusk, whale baleen, wood, and paint, 2 x 6 1/4 x 2 3/8 in. Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Bequest of Thomas G. Fowler, 2007.21.273