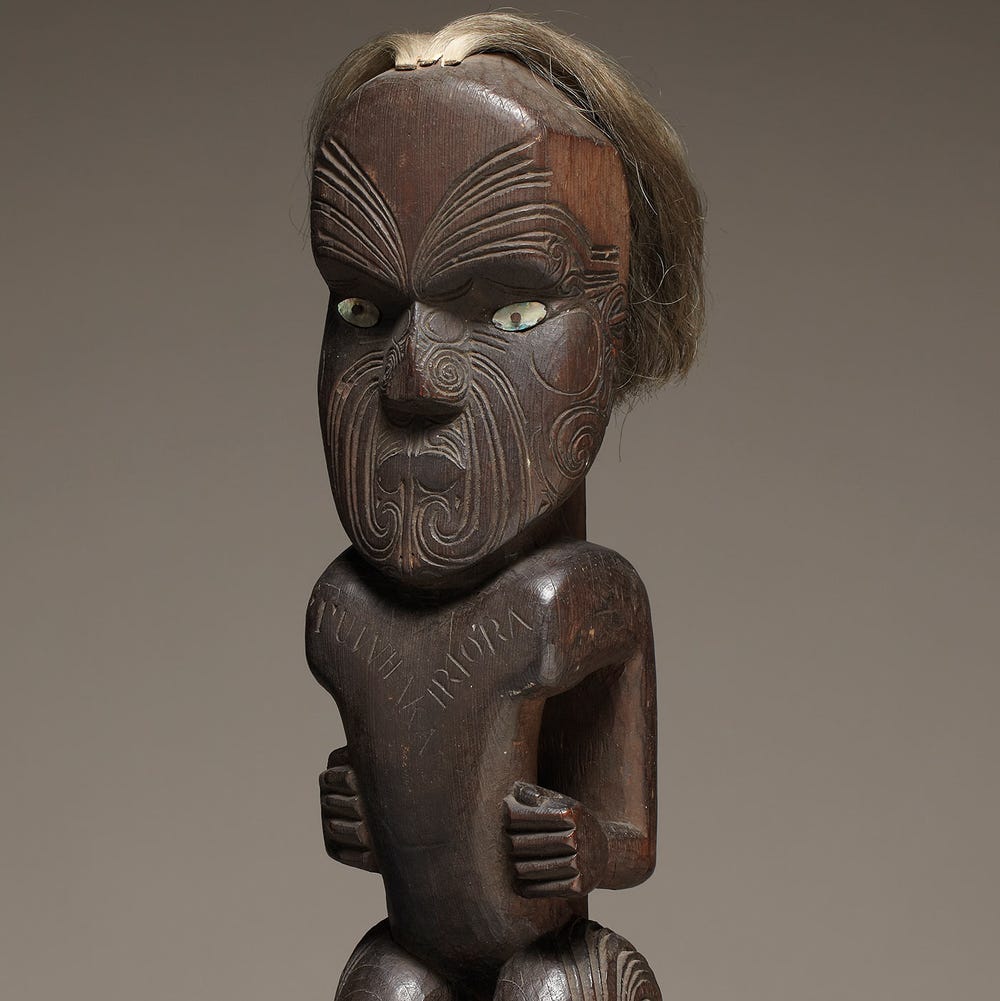

Onoun (Ulul) Island artist, Navigation spirit effigy (osonifei), 19th century - early 20th century. The Federated States of Micronesia, Caroline Islands, Namonuito Atoll. Wood, stingray spines, coconut palm leaves, barnacle, red clay, coconut fiber sennit, pigment, and lime plaster, 16 x 2 1/2 in. (40.6 x 6.4 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Museum purchase, M. H. de Young Memorial Museum, 26168

In the hands of a master navigator of the 19th through early 20th centuries—who had the knowledge to possess it and activate it—this effigy became a powerful spiritual ally to safeguard the navigator and his vessel while at sea.

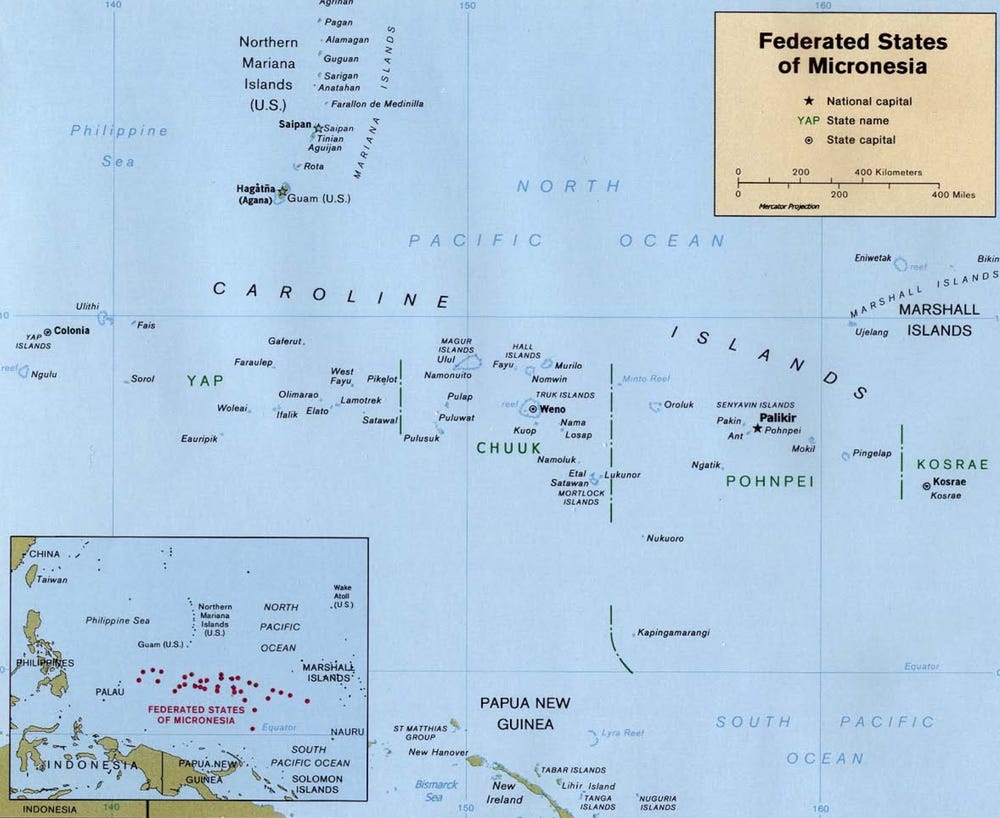

Since their ancestors arrived to settle the coral atolls and volcanic islands of the region, Micronesians have used canoes to traverse the seas surrounding the more than 600 islands distributed across 1,700 miles in the Western Pacific Ocean that make up the Federated States of Micronesia, an independent republic associated with the United States. The distinctive wa, or sailing canoes, are said to be a gift from a heavenly spirit.[1] These wooden outrigger canoes, ingeniously designed for speed and maneuverability with asymmetrical hulls and an interchangeable bow and stern, were fitted with plaited leaf, and later, fabric lateen sails. Expert navigators relied on their knowledge of the winds and weather, ocean currents, and astronomy, and the protection of osonifei, or special navigation spirit effigies, as they made their trade and diplomatic voyages, some hundreds of miles in distance.

Herb Kane, Wa’a Serik of Caroline Islands (C39). Copyright Herbert K. Kane, LLC

—Chief John Tamageron, Yapese navigator [2]Once it is consecrated, the spirit effigy becomes the sharpened weapon that the navigator can use to dispel any disaster in the open seas.

Navigation figures—effigies of seafaring deities imbued with incantations and prayers—offered protection for the navigator from the inherent dangers of the ocean, such as destructive typhoons and storms with high winds and waves that could imperil their vessel.[3] Portable and small in scale but with strong manaman,[4] or cosmic force and power, the figures accompanied the navigator while at sea and were secured to the rigging or placed for safekeeping in a navigator hut located on the outrigger platform when not in use.[5] This rare figure, now in the collection of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, originated from Namonuito Atoll in the Caroline Islands archipelago. The atoll stretches 875 square miles across the Pacific Ocean and is the largest in the Federated States of Micronesia. Onoun (Ulul) Island covers a land area of just under 1 square mile.

Onoun (Ulul) Island artist, Navigation spirit effigy (osonifei), 19th century - early 20th century. The Federated States of Micronesia, Caroline Islands, Namonuito Atoll. Wood, stingray spines, coconut palm leaves, barnacle, red clay, coconut fiber sennit, pigment, and lime plaster, 16 x 2 1/2 in. (40.6 x 6.4 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Museum purchase, M. H. de Young Memorial Museum, 26168

The figure has an abstracted body but defined head with facial features and represents a god of navigation whose name is synonymous with “Spirit of the Voyage” and who sees in all directions over time and space to aid the mariner.[6] The materials making up the figure—wood, stingray spines, and lime—coalesce the Carolinian cosmology of sky, ocean, and island.[7] Stingray spines extend downward from a lime-covered section, and the name osonifei “derives from the stingray spines which were ritually attached with coral limestone containing secret ingredients to the bottom of a carved wooden figure.”[8] A barnacle container, or rokeyok, containing red clay and wrapped in coconut fiber sennit is tied to side of the figure. Fragments of coconut palm strips—applied to the figure during the recitation of chants for protection and to ensure good weather—remain.[9]

Materials – In Detail

- Lime - White paste made by burning coral/shell and then grinding it and mixing the powder with water and a binder to create a paste. This paste is used to attach the two stingray spine legs into the wood figure.

- Stingray spines - Poisonous spines on the tail of stingrays, some more than 15 inches in length, are sharp and rigid with serrations on both sides. “It is said that the spine of a ray in a boat prevents a wandering course.”[10]

- Red clay - Painting of objects such as spirit effigies and canoes was done with red clay mixed with water. The pigment was mixed with the sap of the breadfruit tree to fix the paint to the wood. The red clay found in the barnacle container was used by navigators to anoint themselves when making incantations. Red clay was not available on low-lying coral islands such as Onoun (Ulul) and therefore had to be imported from Chuuk or Yap.

- Coconut palm leaves - Only young coconut leaf strips are used for ritual purposes when calling upon the spirit world for protection or empowerment. It is extraordinary that the leaf fragments remaining on the figure are over 100 years old.

- Coconut fiber sennit - A type of twine or cordage made by plaiting strands of coconut fiber. Sennit is an important material in Oceania, where it is used in architecture, boat building, fishing and in this case as an ornamentation.

Traditional sailing canoe under full sail. Yap, Caroline Islands, Micronesia, Pacific. 1996. © B & C Alexander / Arcticphoto.com

For Carolinians, the ocean has served as the highway between dispersed islands and atolls—many of which sit just feet above sea level—for thousands of years. The sea is a great provider but also has the potential for great destruction, capable of shipwrecking mariners and washing away atolls in a single storm. Throughout history, the unpredictable force of the ocean was marshalled by the exceptional seamanship of navigators who were trained in all that was knowable about their islands, the sea, and the sky. They mapped the stars, island coordinates, and ocean routes in their minds. When disaster approached, they also relied on the power and intervention from the spirit world and their navigation effigies. Canoe voyaging in the region continues today, and while navigators still learn seafaring without instruments, contemporary vessels and their navigation are most often a hybrid of old and new. While navigation figures are generally not taken on canoes today, Christian prayers might be offered instead or in addition to the use of spirit effigies or sacred items. The character of the navigator remains unchanged—“to be fierce,”—or mentally and physically tough, and “to have faith in the knowledge of. . .[the] ancestors.”[11]

Journey to the de Young - Louisa Hitchfield’s Collection

In the early 1900s, Captain John Gordon Hitchfield, and his wife, Louisa (and possibly their daughter Edith, who joined them on previous voyages), set out from San Francisco and spent three years traveling in the Pacific on the Queen of Isles.[12] The schooner was built in San Francisco in 1898 and later fitted with auxiliary engines to improve its operational safety.[13] In 1899, the San Francisco Chronicle reported that Captain Hitchfield, a “fellow of the Royal Geographical Society . . . has devoted years to voyaging among the South Sea Islands on pleasure and trading expeditions.”[14] As captain and owner of the Queen of Isles, he engaged in transporting missionaries from California to Micronesia and trading in copra (dried coconut).[15] Captain Hitchfield was revered for several dramatic rescues of shipwrecked Carolinians and American missionaries.[16]

—San Francisco ExaminerDuring her trip Mrs. Hitchfield gathered curios greater in number and rarer in quality than any other single collection on the Coast. These will probably find a place in some museum in or near San Francisco.

Louisa Hitchfield was a collector on the voyage. In 1904, the San Francisco Examiner newspaper reported, “During her trip Mrs. Hitchfield gathered curios greater in number and rarer in quality than any other single collection on the Coast. These will probably find a place in some museum in or near San Francisco.”[17] In 1905, the navigation spirit effigy and other pieces from the collection were purchased by the City’s Park Commission for what became the de Young museum. The Examiner’s full-page profile about Louisa Hitchfield, including her photograph along with images and racist cartoons of Pacific Islanders, reflects the complexity of transcultural interactions in the Pacific at this time.

The United States and Europe vied for power in the Pacific and imposed colonial rule on many islands to exploit trade and military opportunities. The Hitchfields, like other entrepreneurs, were both participants and observers. While chronicling the perceived threat of cannibalism and decrying societal norms and the dress and beliefs of the islanders she encountered, the article asserts that “[Louisa Hitchfield’s] life on the South Seas was so different from her life in America that it was as if she stepped to another world—a world so beautiful and fascinating that she hopes to pass the rest of her life there.”[18] It is hard to reconcile Louisa Hitchfield’s simultaneous enthusiasm, incredulity, and prejudice. But, the navigation figure that she collected offers a tangible and meaningful link to understanding Carolinian religion and voyaging, past and present.

Acknowledgments:

With sincere thanks to Eric Metzgar, PhD, independent scholar and filmmaker, Triton Films; Vicente M. Diaz,PhD, Associate Professor, American Indian Studies, University of Minnesota; Keith Camacho, PhD, Associate Professor, Asian American Studies, UCLA and the navigators who have shared their knowledge so that we may better understand this historic figure.

Text by Christina Hellmich, Curator in Charge, Arts of Africa, Oceania and the Americas.

Learn more about Oceanic Art at the de Young.

Learn more about the navigators:

Spirits of the Voyage — Preview #1

Jesus Urupiy, a traditional navigator on Lamotrek Atoll in the Caroline Islands of Micronesia demonstrates the use of a navigation spirit effigy to his students. More information about Spirits of the Voyage at: http://tritonfilms.com/spiritsofthevoyage.htm

Islands in the Storm — Preview #2

On Yap in the Caroline Islands of Micronesia, Dr. David Lewis, author of We, the Navigators, The Ancient Art of Landfinding in the Pacific, tells the story of how a sacred barnacle container was used by navigators to ward off storms at sea. Afterwards, he visits with a Yapese navigator, Chief John Tamageron, to learn more about how it was used with a navigator spirit effigy. More information about Islands in the Storm at: http://tritonfilms.com/worksinprogress.html

Lamotrek: Heritage of an Island — Preview #2

Ingtul, a traditional navigator on Lamotrek Atoll in the Caroline Islands of Micronesia recites a chant to ward off storms using a navigation spirit effigy. More information about Lamotrek: Heritage of an Island at: http://tritonfilms.com/lamotrekheritage.htm

Sacred Vessels: Navigating Tradition and Identity in Micronesia (1997)

Examines the canoes of Guam and Polowat, Federated States of Micronesia, as symbols of the survival of native culture and a metaphor of the history of the islands.

Examines the canoes of Guam and Polowat, Federated States of Micronesia, as symbols of the survival of native culture and a metaphor of the history of the islands.

Map of the Caroline Islands

Notes and Sources Cited:

[1] Eric Metzgar, Arts of Micronesia, 1987. Published in conjunction with an exhibition of the same title, presented at FHP Hippodrome Gallery, Long Beach, California, March–June 1987, p. 13.

[2] Eric Metzgar, Islands in the Storm—Preview #2. Video, Triton Films, work in progress.

[3] Email communication with Vicente M. Diaz, April 23, 2020; John H. Brandt, “By Dunung and Bouj,” Natural History 72 (February 1963): pp. 26–28; and Hans Damm and Ernst Sarfert (1935), “Inseln um Truk: Polowat, Hok, und Satawal.” Based on the notes of Ernst Sarfert and Paul Hambruch. Georg Thilenius, ed., Ergebnisse der Südsee-Expedition 1908–1910, II, B, VI, 2. Hamburg: Friederichsen, De Gruyter & Co, p. 14.

[4] Email communication with Vicente M. Diaz, April 23, 2020.

[5] Email communication with Eric Metzgar, April 23, 2020.

[6] Udo Horstmann and Klaus Maaz, “I pierce the sky’s eye” (Weather incantation in Micronesia), Art Tribal 9 (Autumn 2005): p. 77; Metzgar, Arts of Micronesia, p. 7; and Eric Metzgar, Traditional Education in Micronesia: A Case Study of Lamotrek Atoll with Comparative Analysis of the Literature on the Trukic Continuum (PhD diss., University of California, Los Angeles, 2008), revised for PDF internet pagination from original 1991 monogram, p. 270–271.

[7] Augustin F. Krämer (1937) "Zentralkarolinen: Lamotrek-Gruppe, Oleai, Feis." Georg Thilenius, ed., Ergebnisse der Südsee-Expedition 1908-1910, II,B,X,1. Hamburg: Friederichsen, De Gruyter & Company, p. 156; Metzgar, Arts of Micronesia, p. 7.

[8] Email correspondence with Eric Metzgar, April 23, 2020. Osonifei are currently known in the islands west of Namonuito Atoll, between Chuuk and Yap as hosilifei (Lamotrek Atoll) or gosilifei (Woleai Atoll), commonly abbreviated to hos and gos respectively.

[9] Metzgar, Traditional Education in Micronesia: A Case Study of Lamotrek Atoll with Comparative Analysis of the Literature on the Trukic Continuum, p. 270.

[10] Udo Horstmann and Klaus Maaz, “I pierce the sky’s eye” (Weather incantation in Micronesia), Art Tribal 9 (Autumn 2005): p. 74.

[11] Pius “Mau” Piailug (1932–2010), master Satawalese navigator, quoted in “Mau Piailug, One of the Last Wayfinders, Followed the Stars to Tahiti,” Adventure Journal, March 15, 2019, https://www.adventure-journal.com/2019/03/mau-piailug-one-of-the-last-wayfinders-followed-the-stars-to-tahiti

[12] “From Sea and Shore: Auxiliary Schooner Queen of the Isles Arrives from Carolines,” The San Francisco Call, May 28, 1900, p. 5.

[13] Ibid.

[14] “Tidal Waves Sweep the Caroline Group: The Island of St. Augustine Half Washed Away and the Natives Rescued on the Verge of Starvation,” San Francisco Chronicle, April 28, 1899. p. 1.

[15] American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, The Missionary Herald, vol. XCV (Boston: Beacon Press, 1899), p. 176; and “One White Woman on a Cannibal Island.” San Francisco Examiner, Sunday, October 23, 1904, p. 48.

[16] “Tidal Waves Sweep the Caroline Group: The Island of St. Augustine Half Washed Away and the Natives Rescued on the Verge of Starvation,” San Francisco Chronicle, p. 1.

[17] The San Francisco Examiner, Sunday, October 23, 1904, p. 48.

[18] Ibid.