Though not firmly identified, this may be the same artist who created portraits of the Freake and Gibbs families—the artist thus known as the Freake-Gibbs painter. The few surviving portraits from this period provide valuable information about how the upper-middle class lived in colonial New England during the final decades of the seventeenth century. This group portrait in particular also illustrates the ways in which elite families telegraphed their status and power through their children.

The Freake-Gibbs Painter (attrib.), David, Joanna, and Abigail Mason, 1670. Oil on canvas, 39 1/2 x 42 1/2 in. (100.3 x 108 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd, 1979.7.3. Photograph © Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

This painting depicts the three children of Joanna and Arthur Mason, a prosperous Boston “biscake baker” who was described as “an officer of spirit and firmness.” The family’s wealth and refinement are embodied by their children, David (age eight), Joanna (age six), and Abigail Mason (age four), whose elaborate clothing and accessories indicate their elevated social position. The artist made sure to capture the lavish aspects of their dress since, although their attire is typical for the period, the finer details signal their privileged status. Massachusetts law during this period stated that extravagant fashions, such as the children’s slashed sleeves, as well as lace and ribbons, could be worn only by educated families, military families, magistrates, or those with an annual income in excess of two hundred pounds. The details of the Mason children’s clothing suggest their relative power within the larger social structures of the time.

Freake-Gibbs Painter, Elizabeth Clarke Freake (Mrs. John Freake) and Baby Mary, 1671–1674. Oil on canvas, 42 1/2 x 36 3/4 in. (108 x 93.3 cm). Worcester Art Museum, 1963.134. © Worcester Art Museum, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Albert W. Rice

The children also hold emblems of their budding social status. David is shown as a young gentleman, holding a silver-topped walking stick indicating his position as the family’s male heir. His sisters hold symbols of their feminine attributes: Abigail’s pink rose evokes youth and beauty, and a visitor to the colonies some fifteen years later would refer to her sister, Joanna, as “the very flower of Boston.” Both girls wear necklaces made of coral, which was believed to work as a protective charm and was widely worn as a talisman in an era of high childhood mortality.

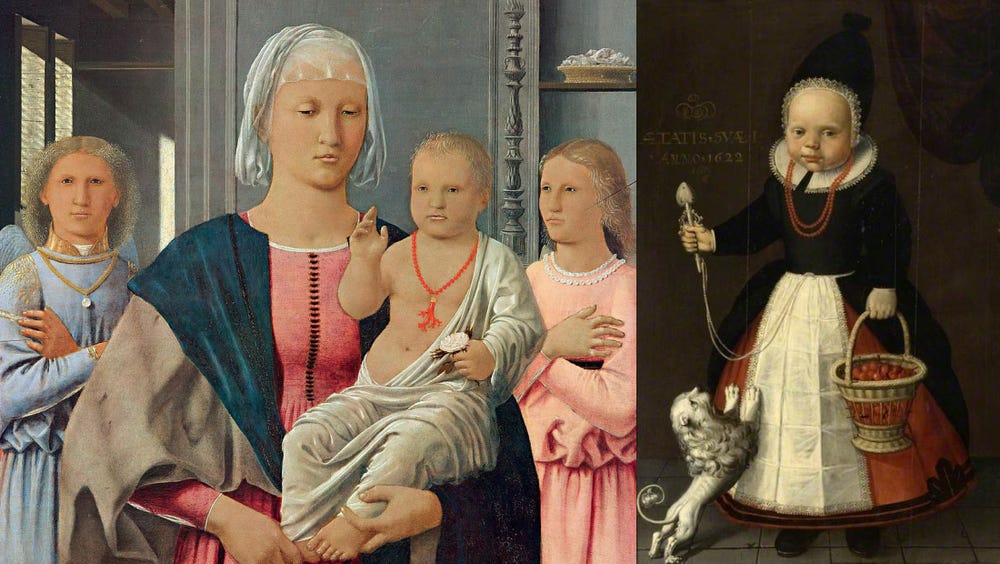

Left: Piero della Francesca, “Madonna di Senigallia,” ca. 1474. Oil on panel, 26 in × 21.1 in (67 cm × 53.5 cm). Galleria Nazionale delle Marche, Urbino. Image courtesy of Wikimedia; Right: Dutch (Friesland) School, “Portrait of a Girl, Aged One, with a Basket of Strawberries,” 1622. Oil on panel, 49 1/2 x 26 1/2 in. (125.8 x W 67.3 cm). The Burrell Collection, gift from Sir William and Lady Burrell to the City of Glasgow, 1944 35.252. Image courtesy of ArtUK.org

Although all three children possess more social power than members of the lower classes, at the young age of eight, David is already on the trajectory to possess more individual power and status than his younger sisters. At the time, women were legally subordinate to men. Circumscribed by oppressive legal structures, women were largely homemakers and responsible for raising children. As elite children like David grew older, they assumed more significant financial responsibilities, while his sisters would have been expected to marry powerful and affluent men of their station.

Although Joanna and Arthur Mason are omitted from this portrait of their children, their influence is felt through the younger generation. David, Joanna, and Abigail signify their parents’ power in absentia, their clothing and accessories a testament to their family’s status. This portrait provides a glimpse into the life of a family whose wealth and its worldly rewards signified their power.

From The Colonial Laws of Massachusetts

“Although several declarations and orders have been made by this Court against excess in apparell, both of men and women, which have not taken that effect as were to be desired, but on the contrary, we cannot but to our grief take notice that intolerable excess and bravery have crept in upon us. . . . It is therefore ordered by this Court, and authority thereof, that no person within the jurisdiction, nor any of their relations depending upon them, whose visible estates, real and personal, shall not exceed the true and indifferent value of £200, shall wear any gold or silver lace, or gold and silver buttons, or any bone lace above 2s. per yard, or silk hoods, or scarves, upon the penalty of 10s. for every such offense and every such delinquent to be presented to the grand jury.”

Text by Lauren Palmor, assistant curator of American art. This text is an excerpt from the selected works publication, de Young 125, available for presale in Spanish, Mandarin, and English from the Museum Stores.