Plaque in the style of the Royal Court of Benin (detail), 16th century, Benin. Bronze or brass, 17 3/4 x 7 in. (45.1 x 17.8 cm). Museum purchase, William H. Nobel Bequest Fund.

What are the Benin Bronzes?

The Benin Bronzes come from Benin City, the historic capital of the Kingdom of Benin, a major city-state in West Africa from the medieval period. Today, Benin City is located within the Federal Republic of Nigeria.

The modern city of Benin is the home of the current ruler of the Kingdom of Benin, His Royal Majesty Oba Ewuare II. Many of the rituals and ceremonies associated with the historic Kingdom of Benin continue to be performed today.

The Benin Bronzes refers to a large group of sculptures that include elaborately decorated cast plaques, commemorative heads, animal and human figures, items of royal regalia, and personal ornaments that were specifically cast in brass or bronze. They were created from at least the 16th century onward by specialist guilds working for the royal court of the oba (king) in Benin City.

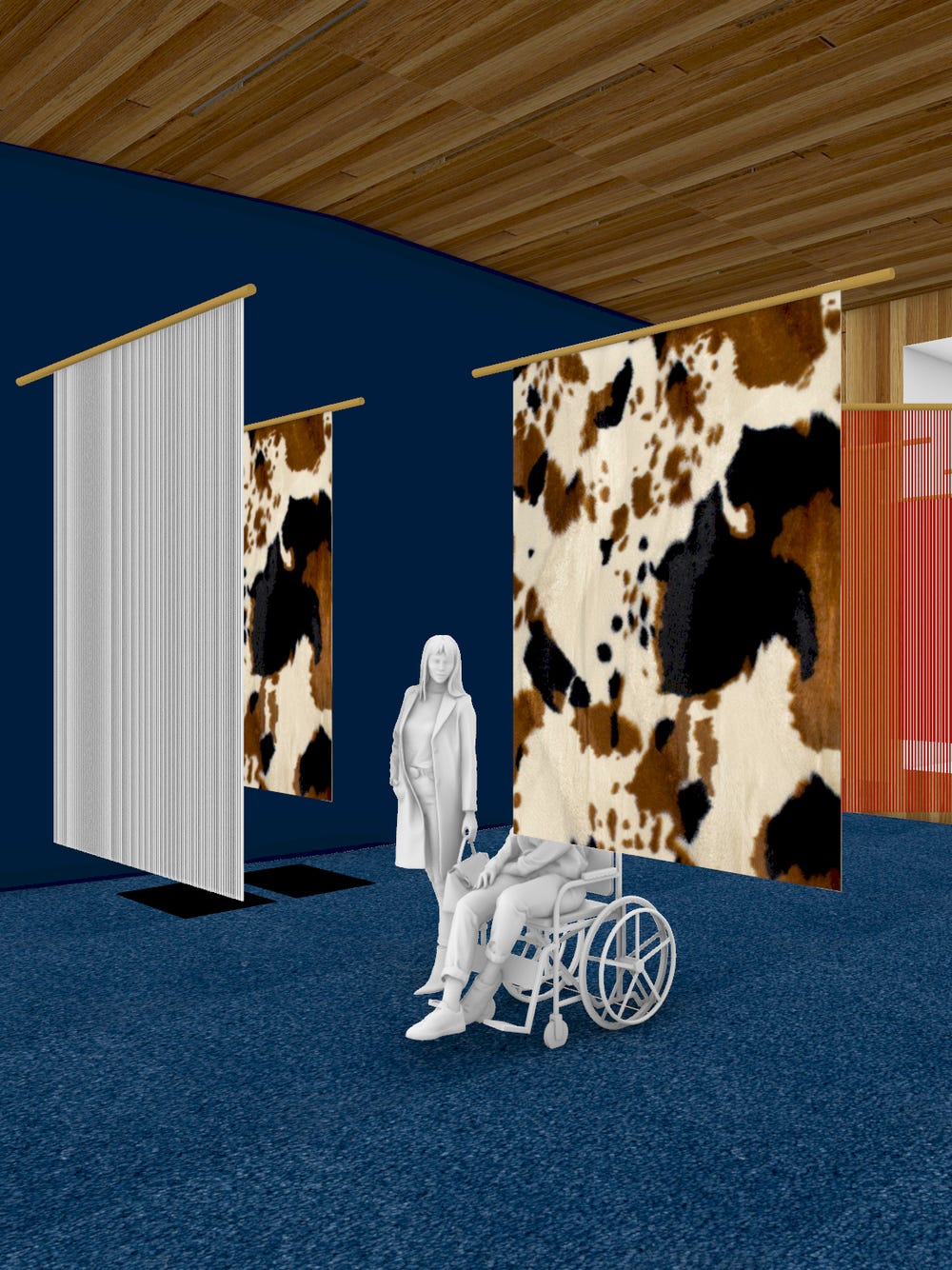

Within the tradition of Benin Bronzes, three examples — a bronze hip ornament, a bronze plaque, and a wooden stool — are conserved at the de Young museum and on view in the African art gallery.

How did this artwork leave Africa?

The Benin Bronzes made their way to Europe as a result of colonial violence. In 1897, the British Empire invaded the capital of the kingdom as part of an imperial campaign waged from 1892 through 1902 to bring modern-day Nigeria under British rule.

The British occupation of Benin City resulted in widespread destruction and looting by British forces. Along with other monuments and palaces, the Benin Royal Palace was burned and partly destroyed. Its shrines and associated compounds were looted, and thousands of artworks of ceremonial and ritual value were taken to London, the seat of the British Empire, as “spoils of war” or distributed among members of the expedition according to their rank.

This included artworks removed from royal ancestral shrines, among them ceremonial brass heads of former obas and their associated ivory tusks. The looted artworks included more than 900 brass plaques, dating largely from the 16th to 17th centuries. Having previously decorated the palace walls, these plaques provide key historic records of the Benin court and kingdom, enabling researchers to better understand its historic practices and cultural traditions.

Directly following the British invasion, around 200 Benin artworks were given to the British Museum by the secretary of state for British foreign affairs, while others were sold on the international art market. In addition to dealers and private collectors, the major clientele for African art at this time were newly established ethnographic museums in Europe.

What happened after Benin City was looted?

Following the British occupation of the city, the king, Oba Ovonramwen, was sent into exile in Alabar, while a number of his chiefs were executed. This violent event marked the end of Benin City’s independence and the beginning of British colonialization in Nigeria. When Ovonramwen died in 1913, his son Eweka II was restored as oba but within the British protectorate. He prioritized a renewal of artistic patronage in Benin City.

Subsequent to the 19th-century dispersal of Benin works, awareness of their extraordinary aesthetic power, beauty, and complexity profoundly influenced Black public intellectuals. Notable among these in the United States were W. E. B. Du Bois, Alain Locke, and artists from the Harlem Renaissance on. At the same time, the Benin Bronzes were relegated to ethnographic museums during the colonial era, reflecting the legacy of their forceful removal and isolation from comparative cultural achievements in Western culture.

In 1960, with the establishment of the Federation of Nigeria as an independent nation, Benin City became the capital of Edo State. In 2016, Oba Ewuare II assumed the title of Benin’s current oba. Since the end of British rule, African people within and outside Nigeria have called for the return of the Benin Bronzes.

What is the museum’s position on the Benin Bronzes?

The release in November 2018 of a report on the restitution of African cultural heritage, written by academics Felwine Sarr and Bénédicte Savoy upon the request of French President Emmanuel Macron, reopened thinking and conversation about issues of cultural patrimony and heritage in light of Africa’s colonial history.

Following the report, the de Young museum organized a public discussion to reflect on the restitution of art from the Benin Kingdom with two international experts of Nigerian historical art, Barbara Plankensteiner, director of the Museum am Rothenbaum in Hamburg, Germany, and a founding member of the Benin Dialogue Group, and Ndubuisi Ezeluomba, the Françoise Billion Richardson Curator of African Art at the New Orleans Museum of Art.

More recently, the museum joined Digital Benin, an international initiative to digitally network the globally dispersed works of royal art from the former Kingdom of Benin. This timely initiative supports museum research into the provenance of colonial-era artifacts.

Thomas P. Campbell, director and CEO of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, explicitly stated in 2021 that the violent legacy of British colonialism in Nigeria “casts a shadow that will only be removed when Western institutions reach generous, equitable solutions with the countries from which their collections originated. Part of that reconciliation will inevitably involve repatriation of objects.”

The museum is actively engaged in the process of educating its board, staff, and visitors about these works and surrounding issues and exploring mutual ways of moving forward with colleagues in Nigeria.