“Art is the Flower”: Floral Stories from the American Art Collection

By Lauren Palmor

May 29, 2020

—Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1902)Art is the Flower—Life is the Green Leaf. Let every artist strive to make his flower a beautiful living thing, something that will convince the world that there may be, there are, things more precious, more beautiful—more lasting than life itself.

Throughout art history, flowers have been a favorite subject for artists, designers, and artisans. Aside from the obvious beauty of blossoms and petals, many floral subjects contain within them additional layers of symbolism and significance. The American art collection features a number of floral pictures connected to artists’ personal stories of adventure, ambition, and inspiration. From personal images of daily life and quiet reflection to global influences and international journeys, these five paintings reflect the rich variety of floral stories that can be found in the permanent collection galleries at the de Young museum.

Charles Caryl Coleman, Azaleas and Apple Blossoms (1879)

Azaleas and Apple Blossoms (1879) is one of about fifteen large-scale Aesthetic still lifes that Charles Caryl Coleman (1840—1928) painted throughout his career. The inventive, attenuated format of the composition recalls a Chinese or Japanese hanging scroll, and this stark verticality elegantly exaggerates the elongation of the azalea branches, stretching upward and bursting into decadent clusters organized with the fragile asymmetry of ikebana, the Japanese art of flower arrangement. This ascensional quality is counterbalanced by the two vessels firmly grounded on the table. The deep red of the stout jardinière contrasts with the white petals of the azaleas, while the pink apple blossoms are set off by the lustrous glaze of their Chinese vase. The vase recalls the so-called “Chinamania” of the 1870s, when Coleman’s fellow Aesthetes, such as James McNeill Whistler, popularized the taste for collecting blue-and-white porcelain in the West. The richly decorated vase in Coleman’s still life features a deer, a symbol of longevity, presenting a stark contrast with the fleeting lifespan of azaleas and apple blossoms.

Charles Caryl Coleman, Azaleas and Apple Blossoms, 1879. Oil on canvas, 71 1/4 x 25 in. (181 x 63.5 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Museum purchase, Roscoe and Margaret Oakes Income Fund, gift of Barbro and Bernard Osher, J. Burgess & Elizabeth Jamieson Endowment Fund, and bequest of William A. Stimson, 2008.9

Coleman was respected by his late 19th-century contemporaries as a leading painter of decorative still lifes. Born in Buffalo, New York, Coleman left the United States for Europe after serving in the Union Army during the Civil War. He lived in Rome from the late 1860s through the mid-1880s, becoming an active member of the city’s creative expatriate community. His studio on Rome’s Via Margutta became known for its displays of rare and exotic objects and textiles, from antique pottery and Japanese fans to Chinese lacquer bowls and colorful maiolica vases. One contemporary writer for Lippincott’s Magazine described Coleman’s studio as “picturesque,” while another correspondent for the Roman News compared it to “a scene from a fairy play [filled with] antique tapestries and medieval paintings and brass lamps and rich oriental rugs, which the magician Coleman has managed to bring together.”[1]

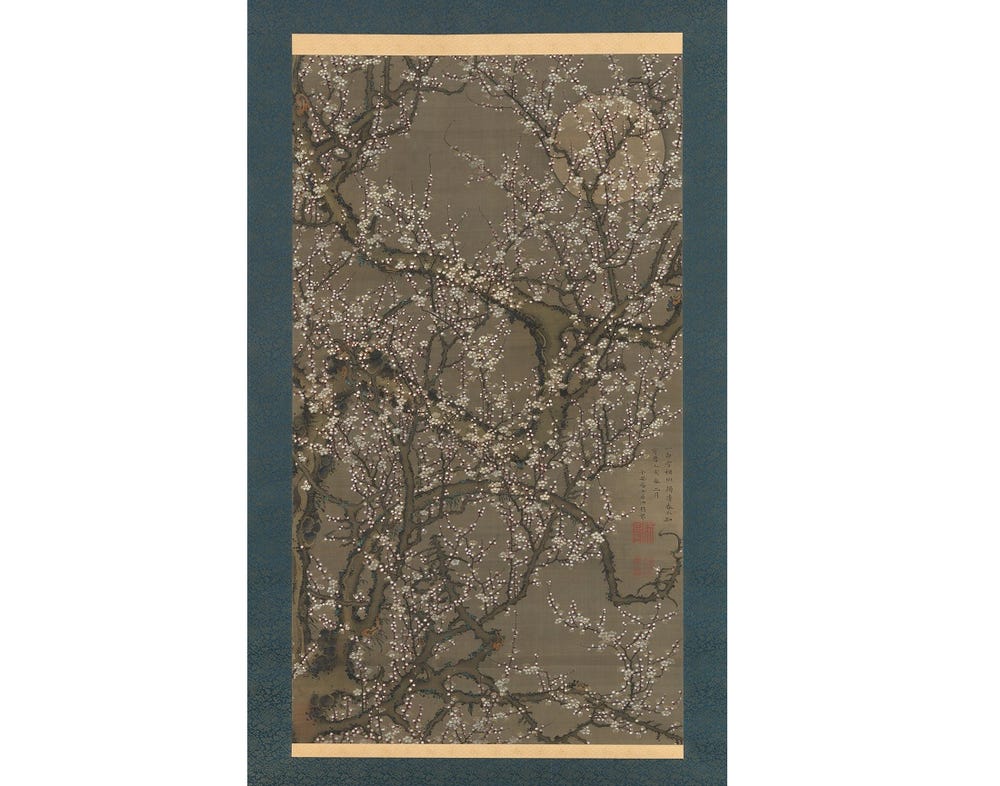

Itō Jakuchū, White Plum Blossoms and Moon, 1755. Hanging scroll; ink and color on silk, 55 3/8 × 31 1/4 in. (140.6 x 79.4 cm). Metropolitan Museum of Art, Mary Griggs Burke Collection, Gift of the Mary and Jackson Burke Foundation, 2015, 2015.300.213

The rich, varied contents of Coleman’s studio represented the material dimensions of the artist’s alignment with the international Aesthetic Movement, which united practitioners across literature and the fine arts who venerated beauty and sought to find harmony between art, nature, and domestic spaces. Azaleas and Apple Blossoms exemplifies the ways in which artists and writers of the Aesthetic Movement inventively combined elements of Western and non-Western culture, engaging in an extended dialogue between the East and West, past and present.

Martin Johnson Heade, Orchid and Hummingbird (ca. 1885)

Orchid and Hummingbird (ca. 1885) demonstrates the remarkable ability of Martin Johnson Head (1819—1904) to dramatically blend the tropical landscape with still life. In this relatively compact composition, a sweeping view of a tropical body of water fills the background, giving focus and attention to the dramatic orchid and tiny bird in the foreground. Heade gives preference to the minor over the major, creating a heightened sense of drama and wonder. While the pairing of flowers and birds had been a practice long established in the history of ornithological illustration, Heade’s images of birds interacting with such dazzling floral varieties as this pink Cattleya orchid are distinguished by the artist’s distinctive presentation of this subject.

Martin Johnson Heade, Orchid and Hummingbird, ca. 1885. Oil on canvas, 15 1/8 x 20 1/4 in. (38.4 x 51.4 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd, 1979.7.49

Heade had long been interested in hummingbirds: “A few years after my first appearance in this breathtaking world, I was attacked by the all-absorbing hummingbird craze, and it has never left me since.”[3] His dedication to the subject was confirmed in 1863 when he traveled to Brazil for the first time. Heade may have been initially encouraged to make this first journey by his friend Frederic Edwin Church, who worked in a neighboring studio in the famed Tenth Street Studio Building in New York City. Church traveled to South America in 1853 and 1857, and sketches from these trips provided a reference for works such as The Heart of the Andes (1859), one of the most popular paintings of the era.

Church’s success with such sweeping tropical landscapes likely inspired Heade’s three Central and South American adventures between 1863 and 1870, which took him to Brazil, Colombia, Panama, and Jamaica. During these excursions he depicted the tropical scenery, flowers, and birds he encountered, and he initially pursued an ambitious project of his own design: a grand, illustrated catalogue of hummingbirds entitled The Gems of Brazil, which was never completed. Heade aimed to document the seemingly endless variety of hummingbirds whose iridescent feathers resembled gems or jewels. He painted these small, fluttering creatures from life, creating inventive compositions that depicted these birds surrounded by lush tropical landscapes.

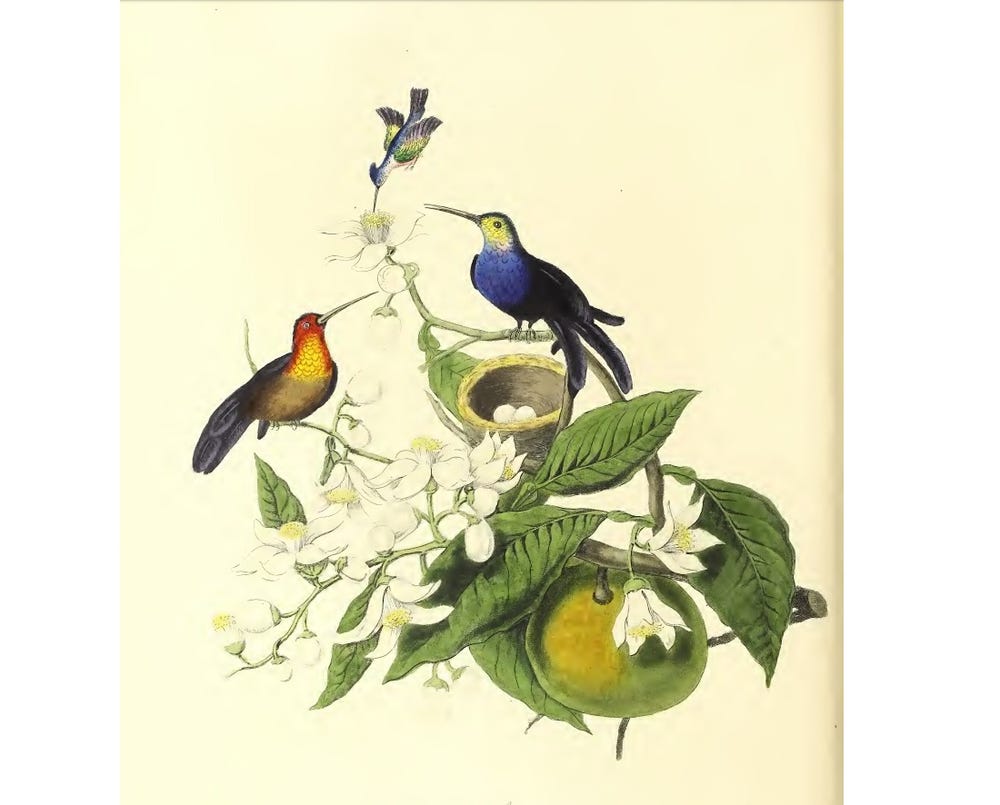

James Forbes, Humming Birds of the Brasils, 1765. Illustration from James Forbes, Oriental Memoirs: selected and abridged from a series of familiar letters written during seventeen years residence in India: including observations on parts of Africa and South America, and a narrative of occurrences in four India voyages. London: Printed for the author by T. Bensley, 1813. Natural History Museum Library, London

It was during his first trip in 1863 that Heade most likely saw orchids in the wild for the first time. After making his third and final trip in 1870, when he traveled to Colombia, Panama, and Jamaica, Heade returned to New York City, where he continued to paint hummingbirds and orchids from memory, referencing the many studies he completed abroad. He utilized his experiences to design such small, lavish works as Orchid and Hummingbird, which he set against exotic backdrops and sumptuous foliage. He continued to produce these tropical pictures into his later years, forever entranced by these exotic birds and blossoms.

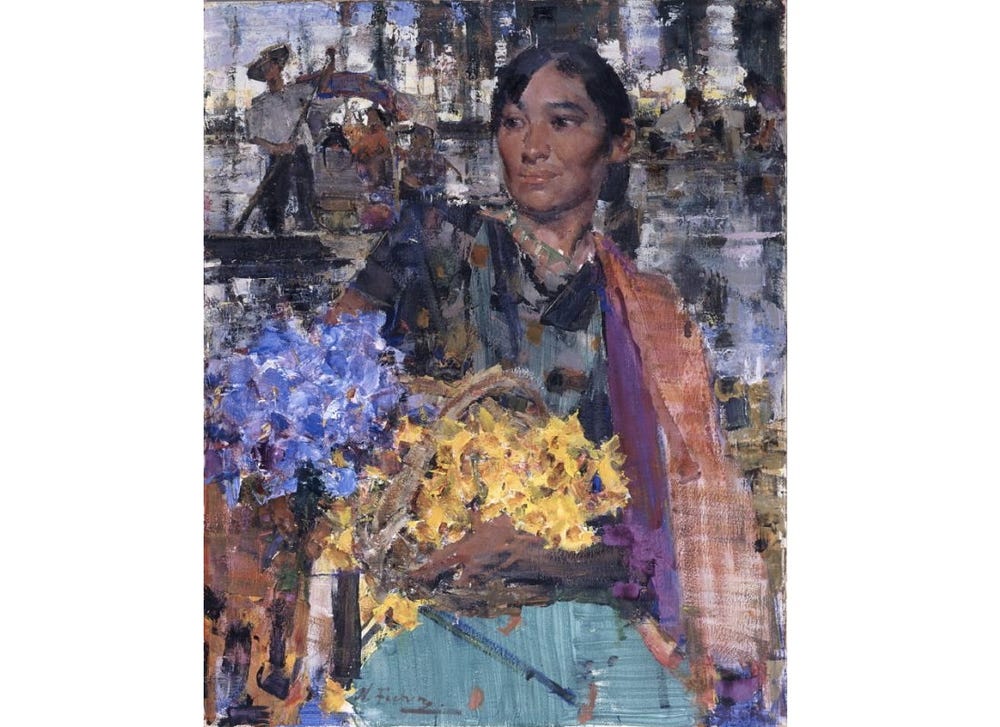

Nicolai Fechin, Flower Girl (1936)

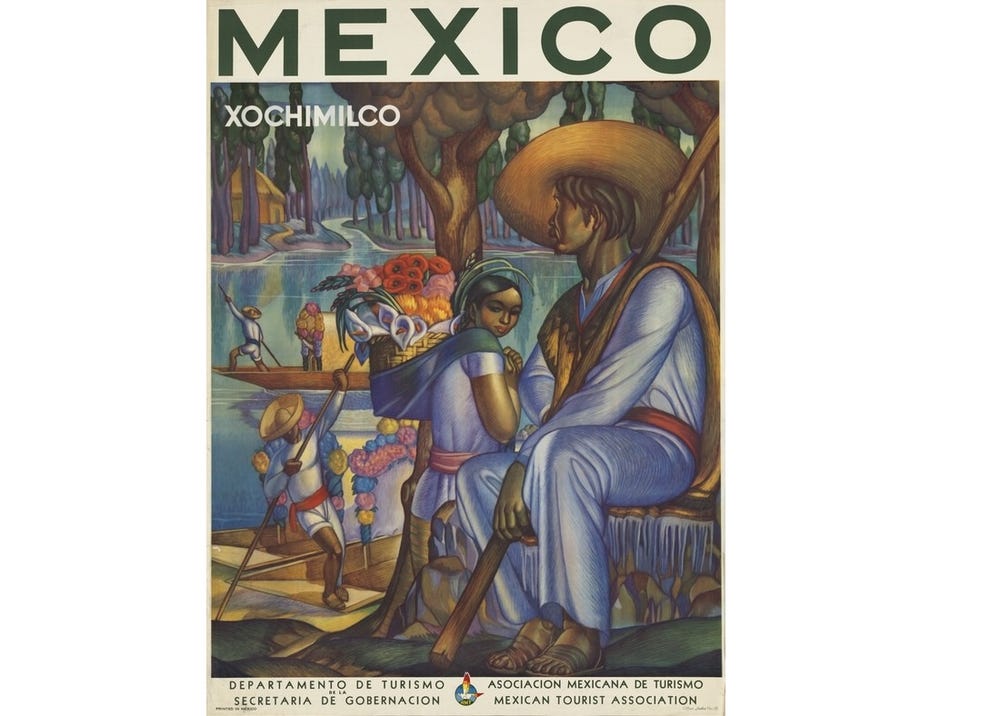

Russian American artist Nicolai Fechin’s Flower Girl (1936) presents a strong example of the artist’s empathetic portraits animated by virtuosic color thickly layered with a palette knife. Fechin conflated realism and abstraction, drawing out certain specific details, such as the woman’s smiling face, while other passages appear as spirited and more abstract gestures. The background of the composition includes a realistic depiction of a trajinera, a small boat used to carry goods across canals, most often found on the picturesque canals of Xochimilco in Mexico City—an area that also boasts a famous flower market. In the foreground, the young woman holds bouquets of vibrant flowers, their deep gold and rich violet tones suggestive of daffodils and irises. Fechin’s penchant for realistic portraiture and precise details contrast with the expressive, abstract blossoms, creating dramatic tension and riots of color.

Nicolai Fechin, Flower Girl, ca. 1936. Oil on canvas, 40 x 32 in. (101.6 x 81.3 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Gift of the Family of Ethel and Raymond Kelner, 2001.198

Fechin was praised early in his career for his “savage, splendid, and heterogeneous” canvases. His early artistic training in Russia academies instilled in him a realistic and disciplined approach to the figure, while his technique was direct and boundless, verging on the abstract. Early on, he exhibited his work internationally and attracted the attention of American collectors who sought to bring him to the United States. After these efforts were stalled by the Russian Revolution in 1917, he finally arrived in New York City in 1923. In 1927, his family moved to Taos, New Mexico, where he developed a reputation for his vivid portraits. Fechin settled in Los Angeles six years later.

Departamento de Turismo de la Secretaria de Gobernacion, Mexico. Xochimilco, ca. 1910–1959. Travel poster. Mexico: Asociacion Mexicana de Turismo (Printed at Offset Galas)

In Los Angeles, Fechin taught classes on Saturday afternoons in his secluded canyon studio. In 1936, he traveled to Mexico with a small group of students on a six-month painting tour of Guadalajara, Mexico City, and Oaxaca (where he met Diego Rivera). Among the group was Katherine Benepe Shackleford, who later recalled that “the sources of supply for materials were fair only; in the south, nothing . . . Artists in the area found other supplies for us.”[3] Despite any shortages of art supplies, Fechin made sketches and took hundreds of photographs documenting the people he encountered on the trip—perhaps this smiling flower seller among them.

Florine Stettheimer, Still Life with Flowers (1921)

Florine Stettheimer’s (1871–1944) Still Life with Flowers (1921) offers a compelling example of the artist’s inimitable approach to floral subjects. A confident departure from realism, Still Life with Flowers depicts an arrangement overflowing with fragrant, eye-catching phlox. Attention is paid not to the individual flowers, but to the sensation of viewing the bouquet as one joyous ensemble. Stettheimer called her floral still-lifes “eyegays,” a word she derived from the term “nosegay” to convey her view that these paintings were intended to please the eye. Her friend, the art critic Henry McBride, wrote in 1946, “Her colors instantly forgot they came from the paint-box and took on the tints of the flowers. When she painted flowers she was never literal in her descriptions of them. . . . the blossoms in her vases wriggled upward with a whimsicality in the stems.”[4]

Florine Stettheimer, Still Life with Flowers, 1921. Oil on canvas, 25 3/4 x 29 5/8 in. (65.4 x 75.2 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Gift of Miss Ettie Stettheimer to the California Palace of the Legion of Honor, 1955.24

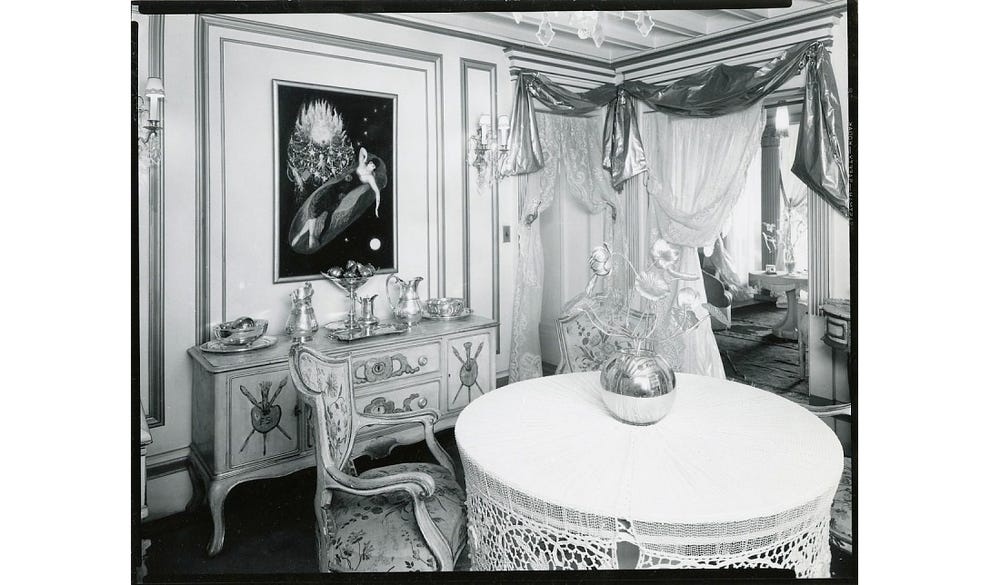

Stettheimer lived in a rarefied world of beauty and creativity. Together with her sisters, Carrie and Ettie she socialized with contemporary artists, writers, and bons vivants at the exhibitions and intellectual salons they hosted at their grand apartment on 58th Street in New York City. There, the “Stetties” mingled with such illustrious guests as Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray, Georgia O’Keeffe, and Alfred Stieglitz. The sisters never married, and their family’s financial security allowed each to wholly devote herself to artistic pursuits: Carrie was a talented miniaturist, Ettie a writer, and Florine a painter.

Multiple flower arrangements visible throughout Florine Stettheimer’s Bryant Park studio (in the background: Portrait of My Sister, Ettie Stettheimer, 1923). Peter A. Juley & Son, Florine Stettheimer's studio, Bryant Park, New York. Black-and-white study print, 8 x 10 in. (20.3 x 25.4 cm). Smithsonian American Art Museum, Archives and Special Collections

Relieved from the pressures of selling her work, Stettheimer’s artistic practice remained a private pursuit. Her paintings depict family, close friends, favorite places, and dreamlike settings—appraised as a group, her body of work suggests a coded, personal mythology. Between her tender portraits and pageants of Manhattan life, Stettheimer painted arresting floral still lifes in her distinctive candy-hued palette. These bouquets have deep biographical significance, as Stettheimer took great pleasure in arranging bouquets for her own enjoyment. Contemporary photographs of her Bryant Park studio (above) show multiple vases of flower arrangements placed throughout the space. Stettheimer’s birthday bouquets were particularly noteworthy: her annual birthday ritual involved picking a bouquet of seasonal flowers—an event she would note in her journals and paint for posterity.

In her poem “Revolt of the Violet,” Stettheimer provides additional insight into her empathetic identification with flowers, which she imbues with their own consciousness: “This is a vulgar age / Sighed the violet / Why must humans drag us / Into their silly lives / They treat us / As attributes / As symbols / And make us / Fade— / Stink.”[5]

Georgia O’Keeffe, Petunias (1925)

Petunias (1925) was inspired by a patch of purple petunias that Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986) first planted at Lake George in New York’s Adirondack region in the summer of 1925, and this is one of a dozen works of various sizes and perspectives that were inspired by those plants. This work is the most elaborate in the series: featuring six blossoms posed at different angles and at various stages of blooming, it evokes the movement of a single flower through space and time. O’Keeffe’s magnified flowers fill the canvas, touching every edge of the picture without directional orientation, each petal animated with velvety textures and crisp contours.

Alfred Steiglitz, O‘Keeffe and Davidson pruning in orchard, 1920. Photograph, 9 x 11.9 cm. Yale University, Beinecke Library, Alfred Stieglitz / Georgia O'Keeffe archive, 10050253

From 1918 to 1934, O’Keeffe made regular visits with Alfred Stieglitz to his family’s property on Lake George, which became her retreat from the bustle of New York City and a source of lasting inspiration. There she found abundant orchards and flower beds—still-life subjects were all around her, literally ripe for picking. O’Keeffe collected the flowers, fruits, and leaves that caught her eye. Working with her friend, chief gardener Donald Davidson, she also selected plants for the garden and tended the fruit trees and flowers around the Stieglitz estate.

Georgia O'Keeffe, Petunias, 1925. Oil on hardboard, 18 x 30 in. (45.7 x 76.2 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Museum purchase, gift of the M. H. de Young Family, 1990.55 © 2019 Georgia O'Keeffe Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Still-life painting had long been central to O’Keeffe’s artistic practice: as a student in William Merritt Chase’s classes at the Art Students League, she was expected to paint a still life every day in advance of a weekly critique. This experience likely heightened the sense of observation that characterizes O’Keeffe’s intense exploration of the color and texture of these vibrant petunias, while the immense scale of each blossom bridges the divide between representation and abstraction.

O’Keeffe’s singular view of the natural world redefined modern art, and her monumental depictions of fruit and flowers affirmed her distinctive relationship with her environment: “I found I could say things with color and shapes that I couldn’t say any other way . . . things I had no words for.”

Text by Lauren Palmor, assistant curator, American art. Learn more about American art at the de Young.

Notes and Sources Cited:

[1] Margaret Bertha Wright, “Gigi’s: A Cosmopolitan Art School.” Lippincott’s Magazine, vol. 27 (January 1880), 10. Writer for the Roman News, 1883, quoted in Adrienne Baxter Bell, "Charles Caryl Coleman on Capri," The Magazine Antiques, November 2005, 142.

[2] Heade quoted in Robert George McIntyre, Martin Johnson Heade (New York: Pantheon Press, 1948), 11; and Theodore E. Stebbins, Janet L. Comey, and Karen E. Quinn, The Life and Work of Martin Johnson Heade: A Critical Analysis and Catalogue Raisonne (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2000).

[3] Letter from Katherine Benepe Shackleford to Mary N. Balcomb. Mary N. Balcomb, Nicolai Fechin (Flagstaff: Northland Press, 1975), 124–6.

[4] Henry McBride, Florine Stettheimer (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1946), 15–16.

[5] Florine Stettheimer, “The Revolt of the Violet,” n.d. Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Yale University. Florine and Ettie Stettheimer papers, Box 8, Folder: Folder 134.