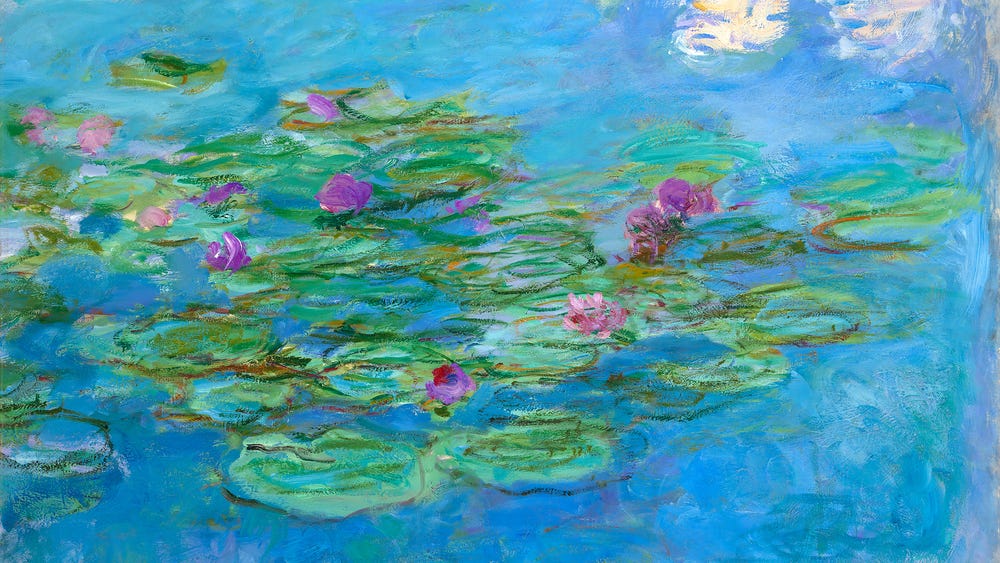

Claude Monet, Water Lilies (detail), 1914 – 1917. Oil on canvas, 71 x 57 1/2 in. (180 x 146 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Museum purchase, Mildred Anna Williams Collection, 1973.3

Monet: The Late Years

Jump to

The exhibition will feature nearly 50 paintings by Claude Monet dating mainly from 1913 to 1926, the final phase of the artist’s long career. During his late years, the well-traveled Monet stayed close to home, inspired by the variety of elements making up his own garden at Giverny, a village located about forty-five miles from Paris. With its evolving scenery of flower beds, footpaths, willows, wisteria, and nymphaea, the garden became a personal laboratory for the artist’s concentrated study of natural phenomena. The exhibition will focus on the series that Monet invented, and just as important, reinvented, in this setting. In the process, it will reconsider the conventional notion that many of the late works painted on a large scale were preparatory for the Grand Decorations, rather than finished paintings in their own right. Boldly balancing representation and abstraction, Monet’s radical late works redefined the master of Impressionism as a forebear of modernism.

In depth

Introduction

By 1913 Claude Monet (French, 1840 – 1926) had secured his position as the most successful living painter in France. This exhibition focuses primarily on the period between 1913 and 1926, when the well-traveled Monet devoted all of his creative attention to a single location — his home and gardens in Giverny, some forty-five miles northwest of Paris. There he created an environment completely under his control. With its evolving scenery of flower beds, footpaths, bridges, willows, wisteria, and water lilies, the garden became a personal laboratory for the artist’s sustained study of natural phenomena. In it Monet found the creative catharsis he needed to persist through a series of personal tragedies, including the death of his second wife, Alice Hoschedé, in 1911; the death of his eldest son, Jean, in 1914; and the international trauma of World War I. The work Monet produced during this period is also marked by his struggle with cataracts: first diagnosed in 1912, he eventually underwent an operation in 1923. In the final chapter of his life and career, Monet remained fiercely ambitious in his approach to painting. Throughout his seventies and eighties, he transformed his technique by enlarging his canvases, experimenting with compositional cropping, and playing with tonal harmonies. Boldly balancing representation and abstraction, Monet’s radical late works redefine the master of Impressionism as a forebear of modernism.

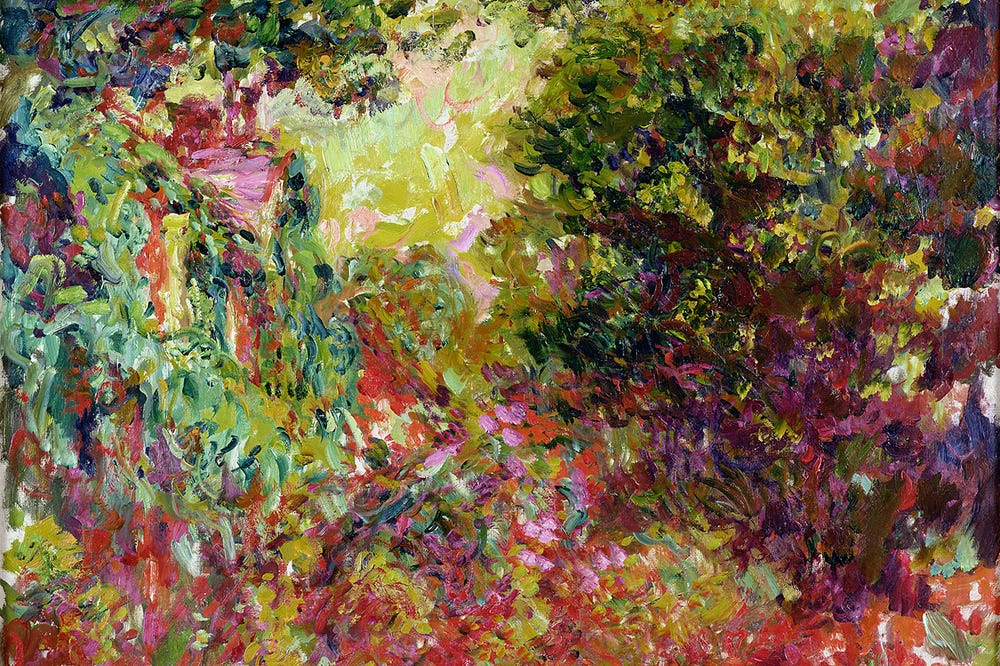

Section 1: Securing success

Claude Monet, Alice Hoschedé, and their combined family of eight children settled in Giverny in 1883, taking up residence at the Pressoir (the Cider Press), as their home was affectionately called. In these years Monet spent time exploring the surrounding terrain. Experiencing greater financial success, the artist purchased the home in 1890 and began an extensive redesign of its surrounding gardens. In 1893 Monet added to his property, acquiring another plot of land across the street from his home. After some debate with the local municipality, he received permission to divert the Epte River to create a pond for cultivating water lilies, a flower he may have first learned about from the horticultural display at the 1889 Exposition Universelle, in Paris. The garden’s design may have also been inspired by Monet’s extensive collection of Japanese prints, which the artist began amassing in the 1860s and had hanging in his dining room. His water lily garden served as a perfect foil to the more traditional flower garden surrounding his home, which was organized in a grid with rectangular flower beds and grand allés. The works in this gallery represent subjects from Monet’s garden that he depicted repeatedly in the final twelve years of his life: the Japanese bridge, the water lily pond, and the rose archway.

Section 2: Into the garden

Throughout Claude Monet’s career, he remained dedicated to close observation of nature, and his elaborate garden at Giverny became a necessary extravagance. He spent great energy and expense studying horticultural magazines, consulting with specialists, and commiserating with fellow enthusiasts. In his early days at the Pressoir, Monet tended the garden with his children; as his designs became more ambitious, he ultimately went on to employ eight gardeners. Monet’s water lily pond was the most important feature of his garden. Ensuring the crystalline quality of the water and the vibrancy of the lilies required one gardener to skim the pond’s surface on a daily basis and dunk the lilies to remove the dust generated by the nearby road (Monet even went so far as to fund the paving of the surrounding roads to prevent such dust from accumulating). The pond offered an ever-changing reflective surface that captured the color of the lilies, the foliage of the adjacent weeping willows, and, at times, the changing effects of the clouds. In 1914, after his self-imposed two-year break from painting following the death of his second wife, Alice Hoschedé, Monet embarked on a new series of water lily paintings. Marked by gestural brushwork and increasingly larger formats, these works are a bold departure from his previous work. Many of these compositions lack horizon lines, resulting in fragmented, often spatially disoriented views. On this same impressive scale, Monet also painted irises, daylilies, and agapanthuses growing at the water’s edge.

Section 3: Grand ambitions

In 1891 Claude Monet started painting in series. His first exhibition of serial works featured compositions of haystacks in the fields surrounding Giverny, while his famous depictions of the facade of the Rouen Cathedral included more than thirty separate canvases. Creating a series of works on a single subject allowed Monet to demonstrate the close observation involved in capturing changes in weather, atmosphere, and light. When first displayed, these works silenced critics who had accused the Impressionists of being overly spontaneous and haphazard in their painting techniques. Monet’s habit of working in series provided the foundation for his most ambitious artistic project: a panoramic mural cycle titled the Grand Decorations, which he began in 1914. Although he created the monumental work in response to observed phenomena within his garden, he painted the actual canvases in his studio, drawing upon his memory rather than painting en plein air. The project took on national significance in 1918, when Monet decided to donate the more than three hundred linear feet of canvases to France as a symbol of peace and in memory of the more than one million French casualties of World War I. Installed in 1927, shortly after Monet’s death, these paintings are permanently housed in the Musée de l’Orangerie, in Paris.

Section 4: A garden of toil and reward

During the later years of his life, Claude Monet continued to work in series, returning to views of his home and the Japanese bridge, rose archway, and weeping willows in his gardens. During World War I, Monet remained at his home in Giverny despite both the departure of most his staff and the shelling outside the town. Scholars often connect the artist’s frequent depiction of weeping willows during this time to a sense of mourning and loss. Though Monet was ceaselessly productive, his correspondences with friends and family attest to his mercurial moods, and visitors to his studio reported seeing canvases that he had slashed or burned. Writing to his friend, the journalist and art critic Gustave Geffroy, Monet stated, “Ah, how I suffer, how painting makes me suffer! It tortures me. The pain it causes me!” In 1924 Georges Clémenceau, the former prime minister of France, wrote to Monet, “Work patiently or angrily—but go to work. You know better than anyone the value of what you have done.” Monet’s struggles with his eyesight undoubtedly increased his self-doubt. First diagnosed with cataracts in 1912, the artist carefully adapted his approach to color by memorizing the placement of paint pigments on his palette. In 1923, with only ten percent of his vision in his left eye and considered legally blind in his right eye, Monet finally agreed to undergo surgery. The procedure, along with corrective lenses, restored enough vision in Monet’s right eye that he was able to return to work in 1924.

Claude Monet’s life at Giverny reflects his approach to his self-defined legacy. Aware that popularity during an artist’s lifetime does not secure one’s position in the art historical canon, Monet sought to establish himself as an integral part of French art history. In 1914, fourteen of his paintings entered the Musée du Louvre, an unheard-of honor for a living artist. Monet generally rejected following or relating his work to artistic trends. Of Cubism, he once stated, “I don’t want to see it . . . it would make me angry.” Nonetheless, his work galvanized generations of artists. During Monet’s lifetime, Pierre Bonnard, Wassily Kandinsky, and Henri Matisse named him as a key influence. After World War II, American artists studying in Paris on the GI Bill, such as Sam Francis and Ellsworth Kelly, found inspiration in the Monet works at the Musée de l’Orangerie. In the 1950s the art critic Clement Greenberg described Monet as belonging to the modern world, while Alfred H. Barr, former director of the Museum of Modern Art, acquired a water lily canvas for the museum in 1955, hailing Monet as the grandfather of Abstract Expressionism.

This exhibition continues to define Monet’s legacy. In the final years of his prolific career, his experimental and creative energies took artistic liberties that reflect a path toward modernism. Monet’s paintings remain a touchstone for artists in the present day — from their origins in impressions of nature to the artist’s abstracted forms realized through expressive color and brushwork.

In the news

Stories

Gallery

Sponsors

This exhibition is organized by the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco and the Kimbell Art Museum, with the exceptional collaboration of the Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris. This exhibition is supported by an indemnity from the Federal Council on the Arts and the Humanities.

Presenting Sponsors

John A. and Cynthia Fry Gunn

Diane B. Wilsey

Lead Support

Clare C. McEvoy Charitable Remainder Unitrust and Jay D. McEvoy Trust

San Francisco Auxiliary of the Fine Arts Museums

Major Support

Ray and Dagmar Dolby Family Fund

Barbara A. Wolfe

Significant Support

The Art Party

Diana Dollar Knowles Foundation

Carole McNeil

MaryBeth and David Shimmon

Generous Support

Estate of Ines R. Lewandowitz

Denise Littlefield Sobel

David A. Wollenberg

Additional support provided by Bank of America, Mrs. George Hopper Fitch, Bob and Jan Newman, Marianne H. Peterson, Maria Pitcairn, and Andrea and Mary Barbara Schultz.