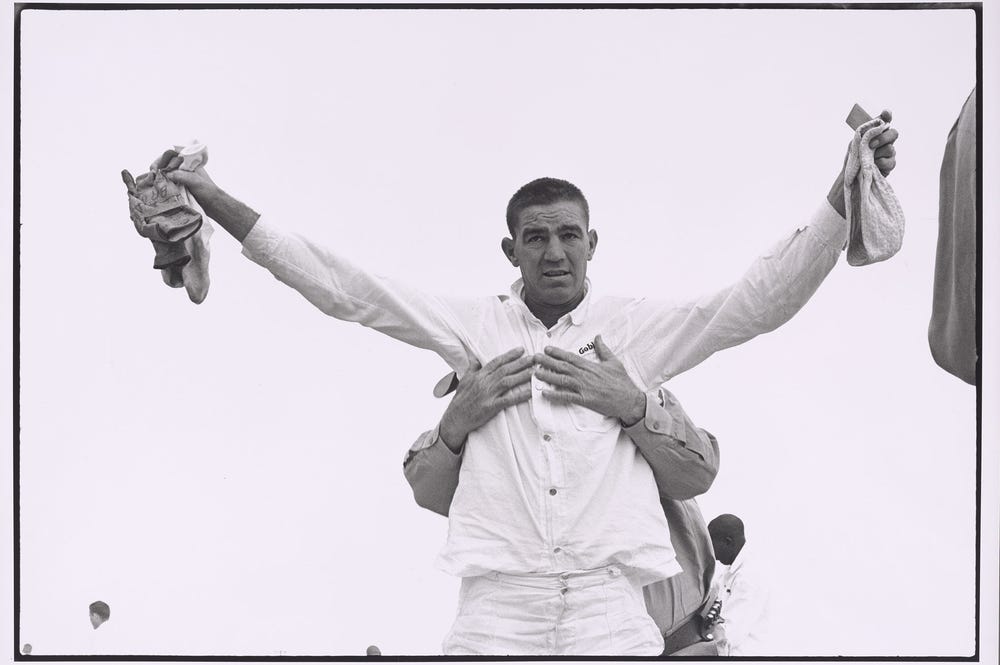

Danny Lyon (b. 1942), Tesca, Cartagena, Colombia, 1966. Cibachrome, printed 2008. 10 1/8 × 10 1/8 in. (25.7 × 25.7 cm). Collection of the artist. © Danny Lyon

Danny Lyon: Message to the Future

Jump to

Danny Lyon: Message to the Future is the first comprehensive retrospective of the career of Danny Lyon (American, b. 1942) to be presented in 25 years. The exhibition is organized by the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco and premiered at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, in summer 2016 before its San Francisco debut.

The exhibition assembles approximately 175 photographs, related films, and ephemeral materials to highlight Lyon’s concern with documenting social and political issues and the welfare of individuals considered by many to be on the margins of society. The presentation includes many objects that have seldom or never been exhibited before and offers a rare look at selections from Lyon’s archives alongside important loans from public and private collections in the United States. This is also the first exhibition to assess the artist’s achievements as a filmmaker.

A leading figure in the American street photography movement of the 1960s, Lyon has distinguished himself by the personal intimacy he establishes with his subjects and the inventiveness of his practice. With his ability to find beauty in the starkest reality, Lyon has through his work provided a charged alternative to the bland vision of American life often depicted in the mass media.

In depth

The exhibition begins with photographs made early in Lyon’s career, when he headed to the South to participate in and document the civil rights movement in the summer of 1962. There, Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) Executive Director James Forman recruited him to be the organization’s first official photographer based out of its Atlanta headquarters. Traveling throughout the South with SNCC, Lyon created photographs such as Arrest of Taylor Washington, Atlanta (1963), as he documented sit-ins, marches, funerals, and violent clashes with the police, often developing his negatives quickly in makeshift darkrooms.

In 1965 Lyon joined the hard-riding and hard-drinking Chicago Outlaws Motorcycle Club and began making photographs like Crossing the Ohio River, Louisville (1966) with a goal to “record and glorify the life of the American bike rider.” The resulting photographs were gathered into the now classic book The Bikeriders, published in 1967.

After moving to a loft in New York City, Lyon began to document the demolition of some 60 acres of predominantly 19th-century buildings below Canal Street in lower Manhattan in late 1966 and into the summer of 1967. The exhibition includes work made during this period, including 82 Beekman Street, New York (1967) and 55 Fulton Street, New York (1967). The resulting photographs, together with Lyon’s journal entries from the period, became the book The Destruction of Lower Manhattan, published by MacMillan in 1969.

Lyon applied to the Texas Department of Corrections to gain access to the state prisons in the fall of 1967. Dr. George Beto, director of the prisons at the time, granted Lyon the right to move freely among the various prison units, which he photographed intensely over a 14-month period. Works such as Shakedown, Ellis Unit, Texas (1968) highlight this searing record of the Texas penal system. Lyon’s aim was to “make a picture of imprisonment as distressing as I knew it to be in reality.”

Tired of the hectic pace of the big city and in search of new surroundings, Lyon headed west from New York in 1969, settling in Sandoval County, New Mexico. He immediately felt a kinship with its close-knit communities of Native Americans and Chicanos. In photographs such as Maricopa County, Arizona (1977), and increasingly in films, Lyon captured a sense of the cross-cultural flow between these disparate groups and how they interacted with the geography of the Southwest.

The exhibition also includes work made in the 1970s and 1980s, as Lyon’s self-described “advocacy journalism” took him to Bolivia and Mexico, where he photographed undocumented workers; to Colombia, where he chronicled the lives of street children; and to Haiti, where he witnessed firsthand the violent revolution overthrowing François “Papa Doc” Duvalier’s dictatorship, as seen in Boulevard Jean-Jacques Dessalines, Port-au-Prince, Haiti (1986). More recently, Lyon made six trips to Shanxi province, in the northwest corner of China, where he photographed the people living in this highly polluted, coal-producing area between 2005 and 2009.

A selection of films dating from 1969 to the present includes Willie (1985), Lyon’s longest and most ambitious film. Willie Jaramillo was a young boy living in Bernalillo, New Mexico when Lyon first met him in 1970. Willie picks up years later, just after Jaramillo’s release from the Penitentiary of New Mexico after a five-year sentence. The film follows Jaramillo’s tragic life and documents how an adolescence spent in and out of prison has transformed him into a paranoid and disturbed young man. Jaramillo died in the early 1990s inside the Sandoval County Detention Center.

Alongside his deep engagement with film, Lyon turned to assembling family albums and creating collaged works he describes as montages, referencing the practice in filmmaking of editing individual sections of film to form a continuous whole.

The exhibition concludes with Lyon’s recent work, which continues the themes he has engaged with throughout his career: documenting social and political change, the people in his community, and the Western landscape. In the fall of 2011 Lyon visited Occupy sites in New York, Los Angeles, Oakland, and Albuquerque. His photographs of the protesters’ camps and their confrontations with police, such as Occupy Demonstration on Broadway, Los Angeles (2011), recall his pictures of the civil rights movement.

About the artist

Born in 1942 and raised in Queens, New York, Lyon was shaped as an artist by the prose of Beat Generation writers and the photo scrapbooks of his immigrant father. He also was inspired by the unvarnished realism of photographer Walker Evans and writer James Agee. With the support of early mentor Hugh Edwards, a curator at the Art Institute of Chicago, Lyon developed the restless, compassionate vision that marks his work in all media. Lyon’s photographs are held in public and private collections throughout the United States and internationally.

After moving from New York City in 1970, Lyon settled in New Mexico and has tackled a broad range of subjects in the Southwest and abroad: life with his family in the mixed Native American and Latino community Bernalillo (just north of Albuquerque); abandoned street children in Colombia; the political turmoil in Haiti; the chaos of life in the booming, polluted industrial outposts in China; and, most recently, the Occupy movement in New York, Los Angeles, and Oakland.

In the news

Films

Born to Film

A young boy emerges from the filmic history of his past, a trailer of the film Born to Film by Danny Lyon.

Dear Mark

A comedy in which the artist’s voice has been replaced by Gene Autry’s. Lyon's homage to his friend, sculptor Mark di Suvero, from footage shot in 1965 and 1975.

I am trying to make a record. . .but I discover my facts through forms and beauty. In the most beautiful pictures the truth is easiest seen, which to me seems like out and out magic. Danny Lyon in a letter to his parents, 1964

Gallery

Sponsors

This exhibition is organized by the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco in collaboration with the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Presenting Sponsor: Anonymous. President’s Circle: The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts. Patron’s Circle: Anonymous.

The catalogue is published with the assistance of the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Endowment for Publications.