Legion of Honor history

High on the headlands above the Golden Gate — where the Pacific Ocean spills into San Francisco Bay — stands the Legion of Honor, a gift of Alma de Bretteville Spreckels to the city of San Francisco. In a city with many riches, the Legion has emerged as one of San Francisco’s greatest treasures. The museum’s spectacular setting in Lincoln Park is made even more dramatic by its French neoclassical architecture.

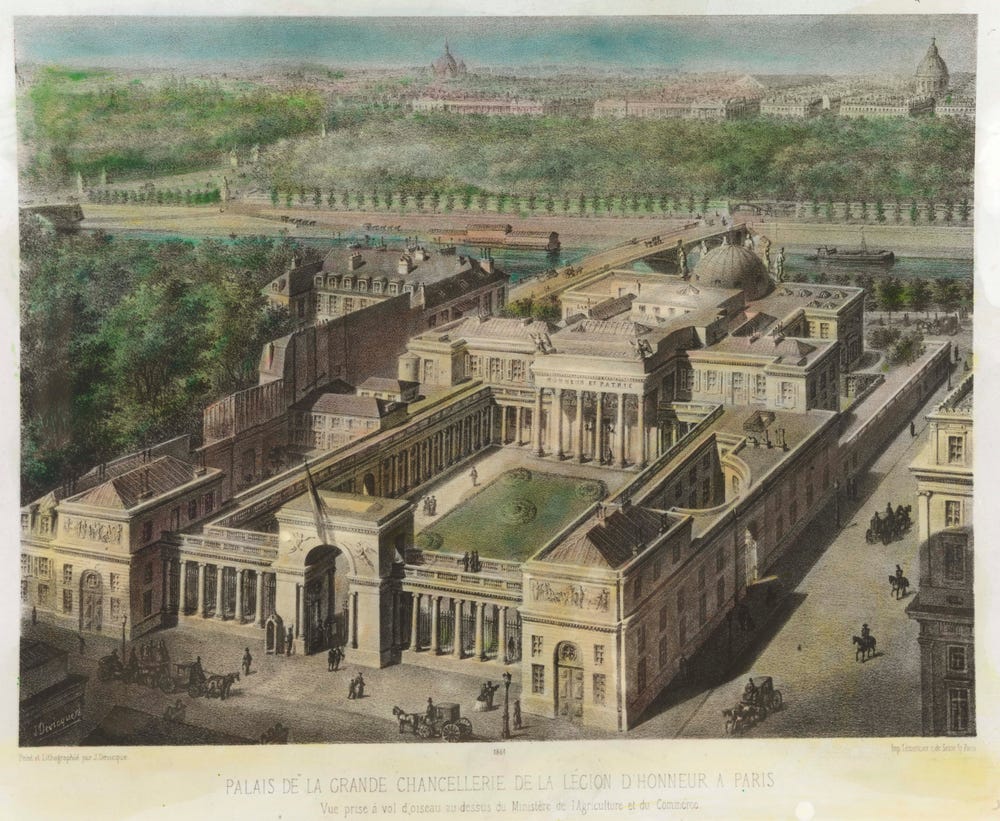

In 1915, Alma de Bretteville Spreckels fell in love with the French Pavilion at San Francisco’s Panama-Pacific International Exposition. This pavilion was a replica of the Palais de la Légion d’Honneur in Paris (originally called the Hôtel de Salm), one of the distinguished 18th-century landmarks on the left bank of the Seine.

The Palais de la Légion d’Honneur in Paris, seen here in a lithograph by J. Devicque, dated 1861, was the architectural model for the new museum in San Francisco. FAMSF Archives, image Joseph McDonald

Alma Spreckels persuaded her husband, sugar magnate Adolph B. Spreckels, to recapture the beauty of the pavilion as a new art museum for San Francisco. At the close of the 1915 exposition, the French government granted them permission to construct a permanent replica of the Palais de la Légion d’Honneur. Unfortunately, World War I delayed the groundbreaking for this ambitious project until 1921.

She wanted the museum to be dedicated to showcasing the art of France, in particular, that of famed French artist Auguste Rodin. It was her goal to bring his work to the West Coast of the United States. With the guidance of her friend, dancer Loie Fuller, who originally introduced Spreckels to Rodin, she traveled to France dozens of times to purchase artworks and explore new names in the French art scene. Much of the original collection of the Legion was built from the artworks she had purchased. Until her death in 1968, Alma Spreckels continued to influence the growth of the museum. She served on the board of trustees, as did her children and extended family.

Construction of the Legion of Honor began in the remote Lands End site in the northwest corner of San Francisco. FAMSF Archives, image Joseph McDonald

The museum was constructed at a remote area of San Francisco called Land’s End, on the site of a 19th-century municipal cemetery, City Cemetery, primarily serving immigrant communities and the poor. The Legion opened on Armistice Day, November 11, 1924, as the California Palace of the Legion of Honor. In keeping with the wishes of the donors to “honor the dead while serving the living,” it was accepted by the city as a museum of fine arts dedicated to the memory of the 3,600 California men who had lost their lives on the battlefields of France during World War I.

In 1923, before the museum’s completion, the American Legion marked its annual convention in San Francisco with a ceremony in the Legion’s Court of Honor. Among the invited guests was a group of disabled veterans and Gold Star mothers who had lost sons in France. It was this event that likely inspired Alma Spreckels to create the Book of Gold and dedicate it to those mothers. She had military records searched for the names and hometowns of Californians who died in the war. A calligrapher then inscribed the approximately 3,600 names in the Book of Gold. The book was displayed in the entrance vestibule of the Legion until 1941, when it was placed in the archives for safekeeping. It is now shown annually during the month of November.

Alma de Bretteville Spreckels lays the cornerstone for the new museum. FAMSF Archives, image Joseph McDonald

The Legion's magnificent pipe organ was built in 1924 by the Ernest M. Skinner Organ Company of Boston. It was given to the Legion for its opening by John D. Spreckels in honor of his brother Adolph, cofounder of the museum. Working with Legion architect George Applegarth, Skinner developed a customized plan to accommodate the 4,526 pipes seamlessly within the structure of the museum. The impressive walnut, ivory, and ebony console, along with its comprehensive range of stops and additional effects, make it one of the world’s finest organs.

The Legion’s first director, Cornelia B. Sage Quinton, came to the museum from the Albright Art Museum in Buffalo, New York, where she worked from 1910 through 1924 as the first female director of a major art museum in the United States. She led the Legion from its opening in 1924 through 1930. In 1931, Lloyd LaPage Rollins became the first director of the de Young in Golden Gate Park, as well as the new director of the Legion, informally uniting the two museums for the first time. He dedicated his tenure to organizing the museums’ collections, devoting the de Young to decorative and graphic arts while focusing the Legion on painting and sculpture. In 1933, Rollins resigned and German scholar Dr. Walter Heil became the director of both museums. Heil focused on collecting fine art, making significant acquisitions of European paintings.

Due to personal conflicts with Alma Spreckels, Heil resigned as director of the Legion in 1939, but continued as director of the de Young. Thomas Carr Howe, Jr., Heil’s assistant since 1933, was made director of the Legion, a position he held until his retirement in 1968.

Under Howe’s direction, the Legion grew from a museum focused on French art to a highly respected comprehensive institution of fine art. In 1951, he oversaw the founding of the Achenbach Foundation for Graphic Arts (AFGA), which took charge of the museum’s collection of works on paper. Today, with over 90,000 works of art, AFGA is one of the largest collections of works on paper in the world.

In 1972, the Legion formally merged with the de Young to create the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco (FAMSF). Through this merger, Ian McKibbin White, who had been director of both museums since 1970, reorganized the collections, establishing curatorial departments for painting, sculpture, decorative arts, prints and drawings, and the arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas. The French painting collection was moved from the de Young to the Legion. Today the Legion holds the collections of European painting, sculpture, and decorative arts, ancient art, and graphic arts.

Applegarth’s design for the Legion was a three-quarter-scaled adaptation of the 18th-century Parisian original and incorporated the most advanced ideas in museum construction. The walls were 21 inches thick, made with hollow tiles to keep temperatures even. The heating system eliminated aesthetically offensive radiators and cleansed the air of dust with atomizers. Seven thousand cubic yards of concrete and a million pounds of reinforcing bar went into the structure. However, an assessment performed in the 1980s showed that the landmark building needed to be made seismically secure.

Between March 1992 and November 1995, the 71st anniversary of the museum, the Legion underwent a major renovation led by architects Edward Larrabee Barnes and Mark Cavagnero. The project included seismic strengthening, building systems upgrades, restoration of historic architectural features, and an underground expansion that added 35,000 square feet. Visitor services and program facilities increased, without altering the historic facade or adversely affecting the environmental integrity of the site.

During construction, a major excavation project was conducted to remove and rebury the remains from about 800 burials from the former City Cemetery (on which Lincoln Park and the Legion of Honor stand). When the cemetery closed in 1900, less than 1,000 of the estimated 10,000 to 20,000 burials were removed, and they still remain underneath the park today. In October 2022, the City of San Francisco designated City Cemetery as a landmark to honor the memory of the 19th-century San Franciscans buried there.

Court of Honor. Photograph Richard Barnes

The 1995 renovation realized a 42 percent increase in square footage, including six additional special exhibition galleries set around a glass pyramid skylight that sits atop the Rosekrans Court and special exhibition galleries located below. The pyramid is a key focal point alongside Auguste Rodin’s The Thinker.

On March 14, 2020, the Fine Arts Museums closed due to the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2021, the Legion reopened to the public.

November 11, 2024 marks the 100th anniversary of the Legion of Honor.